The Fashion Image after Nan Goldin

According to many, fashion is superficial—it is about surface, exaggeration, frivolity. It is, both as a sensibility and a process (the act of getting dressed), about adopting and embracing a disguise, a cover-up. Fashion, at its best and its worst, relies on an acceptance of the fake—the external. Fashion photography is, then, a festival of trickery, a heady, multilayered performance.

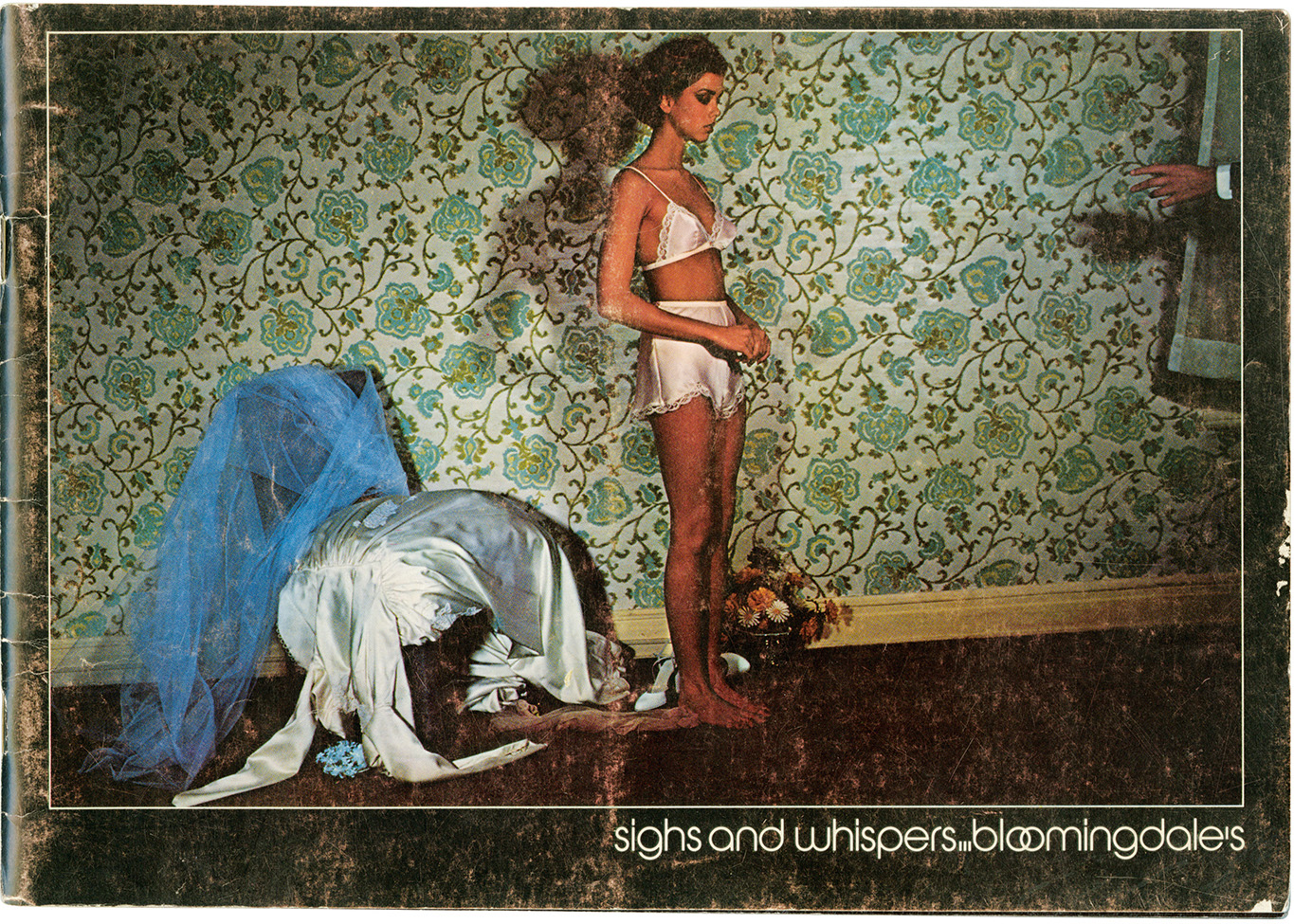

Ironic, then, that Nan Goldin, a photographer whose work is so frequently described as “truthful,” who makes pictures about the internal—pictures that, like jolts to the heart, move us, through the sheer relief of recognition and emotional relatability—is a fan of the fashion image. Goldin discovered fashion photography in the early 1970s through the work of Guy Bourdin. She was particularly enamored with his shoe advertisements for Charles Jourdan and his 1976 lingerie catalog for Bloomingdale’s, Sighs and Whispers (incidentally, the only “book” of Bourdin’s work published during his lifetime).

Goldin also loved Cecil Beaton and Louise Dahl-Wolfe, who was a pioneer in getting models out of the studio and to locations. Writing in Nan Goldin (2010), Guido Costa says that Goldin’s early works “aspire to a sort of fashion-magazine glamour, and look more towards Vogue than to the classical traditions of photography.” And yet, he says, “There is too much life, too much truth in them—consciously or unconsciously, they reject entirely the language of pretense or illusion. In short, these photographs have the roughness typical of reportage, but their context is different, more intimate and private, more participatory.”

It is the “truth,” to quote Costa, in Goldin’s images that has shaped the significant influence her work has had on young image makers and, in a vaguely appropriate cycle, within the landscape of fashion publishing, where her pictures have been rehashed, referenced, and everything in between.

© Estate of Corinne Day and courtesy Trunk Archive

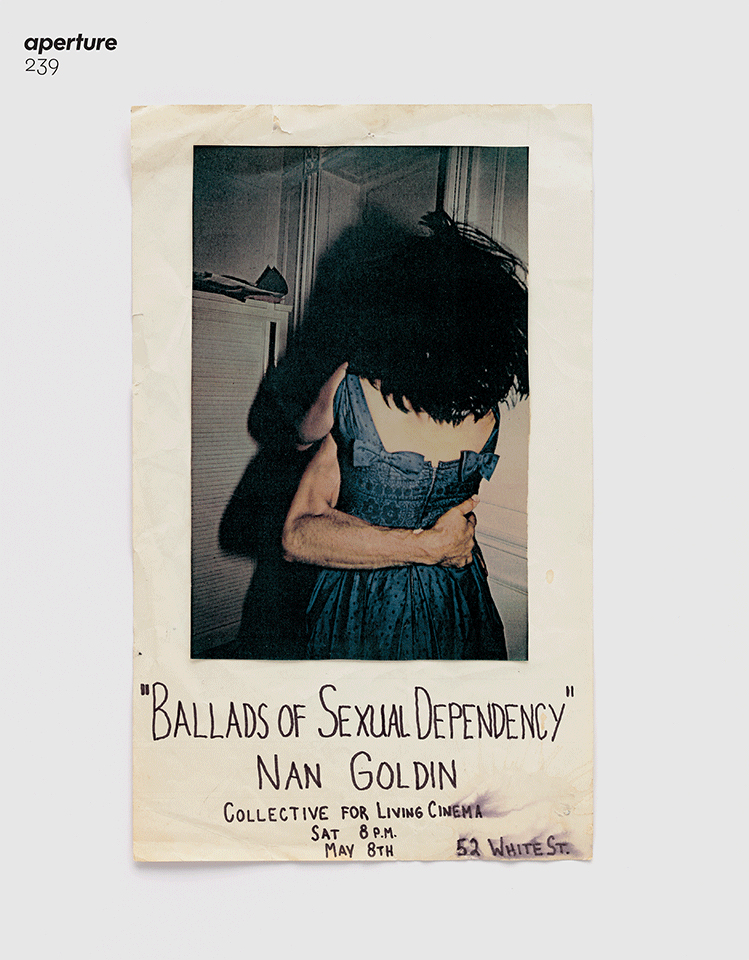

In the 1990s, one saw the specter of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1983–2008) in the goading grittiness of Corinne Day, whose images pushed for a balance of shock and tenderness toward her waifs and strays. In her personal writings, Day described discovering the book during a 1992 trip to New York, at a time when she was trying to convey her experiences through commercial magazines. “I wanted the ordinary person to see real life in those pages,” she writes. “I found Nan Goldin’s and Larry Clark’s work liberating and their work also validated the way I had started to take photographs myself.”

During the fashion magazine boom of the 1990s, dirt, heartbreak, hedonism, and, on occasion, drug use became something like props, wheeled out to convey rebellion or cool. Such a look is neatly summarized in Fashion: Fashion Photography of the Nineties (1998), in which we see Day’s subjects thrashing around in run-down apartments and hotel rooms. We see Kristen McMenamy, half-dressed, a fine, thin scar on her belly, lipstick scrawled on her skin, in images by Juergen Teller from 1996. We see fraying carpets and chipped paintwork and rumpled bedding and discarded clothes and as-they-are models with charged yet insouciant expressions in work by Jack Pierson, Paolo Roversi, Wolfgang Tillmans, and their peers.

Courtesy the artist

Today, Goldin’s influence can be seen in the vogue for fashion images that seemingly appear raw, real, authentic (a word that litters contemporary culture), or simply unretouched. The desire among young photographers to make such images is sparked, in part, by the success of newer image makers such as Ethan James Green (a Goldin admirer) and Jamie Hawkesworth (a devotee to Nigel Shafran, another champion of understated poignancy and realism), who have attracted commissions for their easy daylight, apparently stumbled-upon locations, and often street-cast subjects.

Courtesy the artist

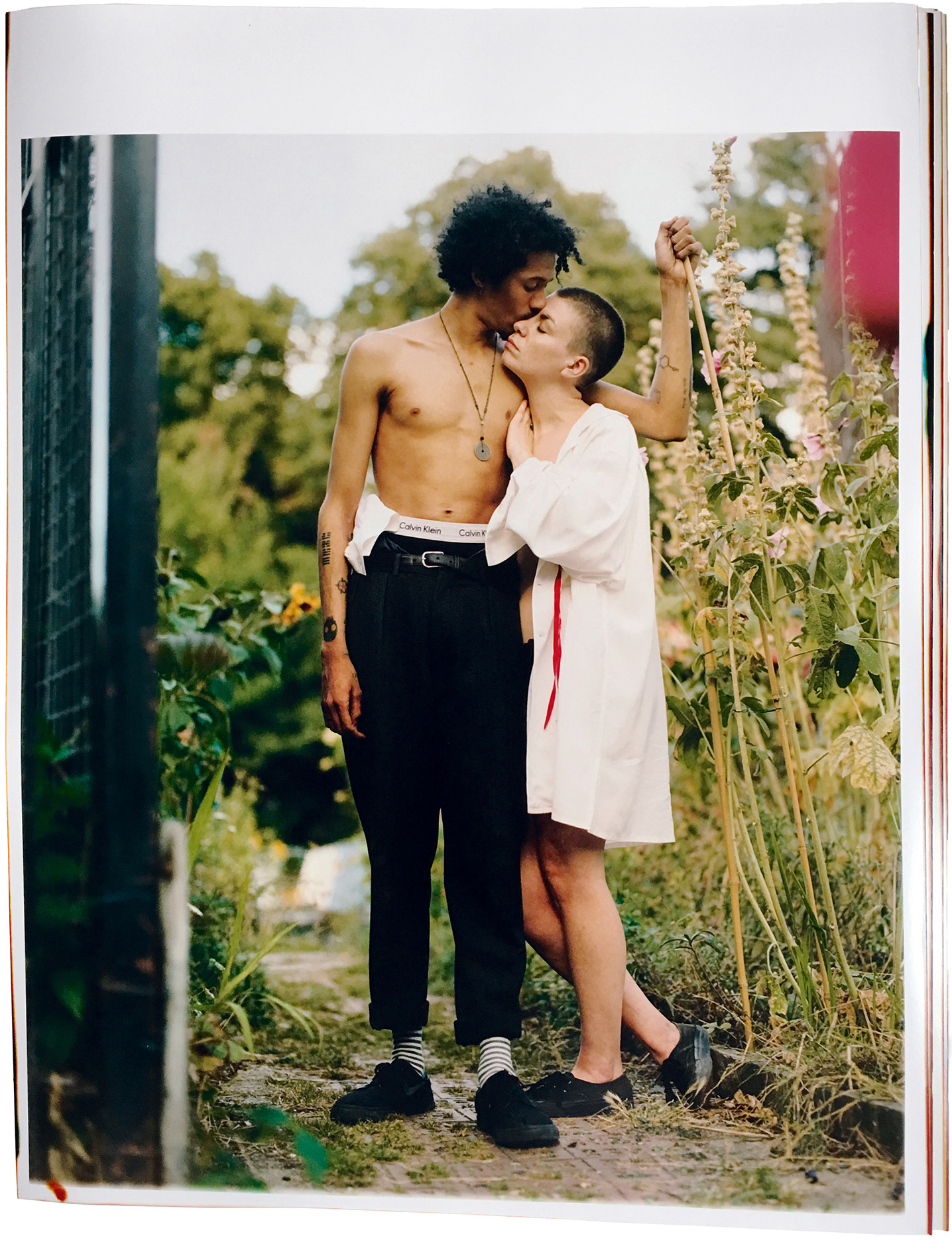

We see Goldin’s shadow on the balance of explicit sensuality and gentleness in Markn Ogue’s Lovers Series (2016–ongoing), which shows young couples entwined. We see it in the calm quietness of Jesse Gouveia’s images. We see it in the liberated, unselfconscious subjects in the work of Annie Powers. We see it in the conviction Guen Fiore has in the importance of showing women’s bodies as they are. Fiore cites Goldin as a key inspiration, pointing to images such as Amanda crying on my bed, Berlin (1992) and Rise and Monty kissing, New York City (1980) as references. “I like to think that I can bring back a hint of honesty in my work, proposing a variety of young women portrayed with simplicity,” she says.

Fashion has flirted with truth pre-Goldin. In the catalog for the Face of Fashion, an exhibition staged at London’s National Portrait Gallery in 2007, Vince Aletti writes, “Fashion magazines have always had a troubled relationship with reality; it’s often in their interest to keep it at bay.” Yet, he continues, they are in tune with cultural shifts. “After the austerity, sacrifice and can-do pluck of the war years, the exuberance of the late 1940s and 1950s was tempered with a new sense of realism . . . the gilt-edged romantic fantasies and neoclassic conceits of an earlier era gave way to a kind of stylized reportage. . . . Authenticity replaced theatricality.”

Courtesy the artist

One doesn’t need to look far to identify sociocultural reasons for the current quest for a semblance of authenticity or truth. Is it a reaction to the explosion of fashion images in other, new, contexts, beyond the magazine—e-commerce images, influencer selfies, Instagram posts—most of which embrace a sort of sanitized, pouty, cartoonish quality, their tweaking done, in many cases, via apps such as Facetune rather than Photoshop? Or is it that in times of climate crisis, when issues of sustainability are more visible, something that promotes high production, or high glamour, simply feels in bad taste? Perhaps, one could simply put it down to cycles; few could argue with the view that nostalgia is rampant in creativity today.

This focus on authenticity has to do with issues of representation. For so long, fashion failed to expand its vision beyond a thin, white body; image by image, it proved itself a censorious critic of anything beyond this narrow fantasy. Today, forums for criticism have expanded; the backlash is loud. “Fashion changes direction every time society is asking for something new and different,” says Fiore. “Nowadays people have a strong voice and are demanding for a more realistic standard of beauty, minorities want to be represented. Beauty as we knew it almost doesn’t exist anymore.”

Courtesy the artist

“For fashion today, reality often means casting people who don’t look like models,” says Gouveia. “Five years ago, you couldn’t use a kid in a piece of your own personal work and then have a commercial client come along and use that same kid on a billboard. It feels significant. People really want to be a part of movements in image making—they think, I believe in those kinds of pictures so I want to make those kinds of pictures.”

Today, a moral quality is given to fashion images that look like real life—they are presented as a step forward. One must be careful, however, to recall that the agents of construction—the stylist, the glam team, the casting agent, the location scout—are still at work; their contributions have just been better disguised. Clients are usually moneymen—they see that a veneer of realism edifies the product, the brand, the consumption, and makes people feel better. Look, it’s just a girl on the street, just like you. “It’s meant to come across as reality, but really it has so many filtrations happening,” says Gouveia. “A model could have just walked into the studio an hour before, maybe she doesn’t know the photographer, she has her hair and makeup done, but it’s sold as something intimate or private.” To acknowledge that this is not a documentary image, and to do so boldly, is perhaps more honest: “Is it ‘realer’ for a fashion shoot to look like a fashion shoot—to show the glitter?”

Courtesy the artist

In general, truth is a dangerous word when one is talking of photographs. The relationship between the two has been thrashed out by thinkers since the medium’s inception. In Diving for Pearls, Goldin’s 2016 book, Glenn O’Brien writes, “From its beginning, photography has been the most magical medium and in art, entertainment, and propaganda, it is the greatest liar of all, making the impossible appear palpably true and validating falsehoods.” The title nods to a quote from Goldin’s friend, the photographer David Armstrong, who said that making pictures is like “diving for pearls.” Goldin writes of his observation that “if you took a million pictures you were lucky to come out with one or two gems.” As implied, the editing process moves an image further away from reality—the banal or mediocre, the uneventful (the humble context, perhaps) are removed.

“Most people don’t really understand what photography is,” says Nick Knight, the British fashion image maker. He is drawn to the craft of making pictures—elaborate lighting, experimental postproduction techniques—though his early documentary Skinhead project (1982) has had a great influence on numerous photographers. (He argues that his heavily worked fashion images are no less “truthful” than his Skinhead images, as his intentions—the desire to “show people things they cannot see”—were the same.) Knight prefers the title image maker to photographer. “The sooner that we understand that photography and image making, are not in any way to do with the portrayal of reality, the better,” he says. “Humans experience reality as a progression of emotions and desires and fears and loves, different feelings which are based on what’s just happened, what’s happening next.” A single snippet can never show that. And photographers will always manipulate, however subtly, whether with the lens, the printing, the shadows, the contrast, or the “diving” Nan refers to. According to Knight, “The idea that it’s all down to the moment when the shutter lifts and the light-sensitive material is exposed, and nothing else outside of that is valid or true, is a real misunderstanding of photography.”

The “real” look, Knight reminds, is just “another filter.” “Nan’s pictures are great love poems they speak about the difficulties, and the beauty, of life. You connect with the emotions, not the surface plasticity of the image. Of course, the plasticity can easily be reproduced for scenes that don’t have any depth of emotion.”

Courtesy the artist

Maxwell Granger, a young image maker from the North of England, whose portraits are unfussy and vaguely droll, is similarly wary of the many fashion briefs asking for relatable, so-called authentic images. “No one really knows what that means,” he says. “People seem to think that something that looks candid is authentic, but I don’t believe that. There is this trend for images where people are not posed—but to get someone to stand there and ‘not pose’ is, if course, posing them. Take my mum, if she had a picture taken of her, it wouldn’t be authentic for her to just candidly stand there. It would be authentic for her to pose, because that is who she is.”

The idea that artifice can be somehow truthful is central to understanding Goldin’s work. This is where her understanding of fashion is so interesting—she sees that the surface is central to our sense of self, to the process of being, to happiness, confidence, love, life itself. She takes stylization seriously; it’s obvious from her photographs of great looks, of performers and drag queens, of nights out dressed up, of makeup smeared and newly applied. Look, she seems to say, The surface creation may speak more of reality than the unmarked, untweaked body underneath. Look again: Isn’t all self, all gender, simply a performance? In that case, how can any photograph be truthful if the subject matter, the person in it, is a construction—an act, a cover-up, a dreamed-up fantasy?

Hilton Als put it best in his 2016 profile in The New Yorker, “Nan Goldin’s Life in Progress,” when discussing Goldin’s images of the performer Suzanne Fletcher in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. “The images are a tender evocation of a young woman who shows the camera as much of her real self as she can.” As much of her real self as she can. And, in turn, the camera captures as much as it can, and as much as Goldin intends (and, to an extent, as much as a certain slither of chance allows). Goldin is aware of the camera’s slippery nature, savvy to its limitations, serious about its power. The punch is the pathos—what we read into each image, what we imagine, and how much of ourselves we bring along to each viewing.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads.”