George Floyd, Gordon Parks, and the Ominous Power of Photographs

From the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter, can images help fight injustice?

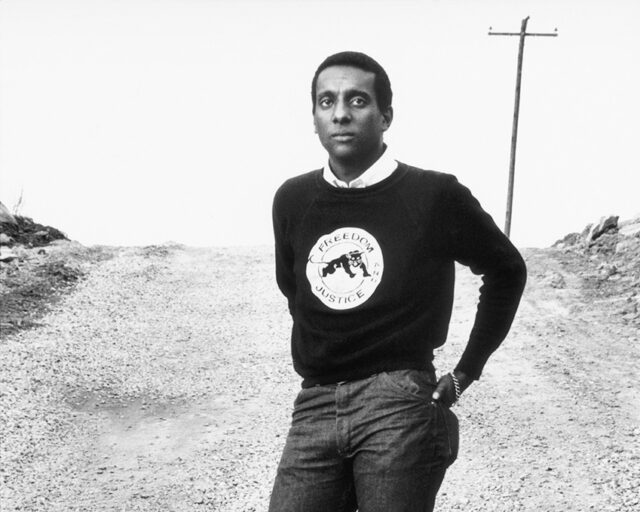

Gordon Parks, Malcolm X Gives Speech at Rally, Harlem, New York, New York, 1963, 1963

“I find it difficult to look at these photographs without flinching from the memories and from the anger they invoke. But I must look. I must remember, as you must. For this was history in the making. Like it or not, you cannot hide from the camera’s eye.”

—Myrlie Evers-Williams, foreword to The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History, 1954–68, 1996

As I reflect on photography and protest, I see it as my life in America from a lived experience to an act of memory. I am troubled by the images I’ve seen over the last two weeks, and I have been asked—by various people—what these images mean to me. Black death has been photographed, broadcasted, painted, recorded, tweeted, and exhibited for the past ninety days. It has been nine days since a teenager posted footage of George Floyd’s murder. It has been nine days of collectively watching George Floyd’s last moments of life, seeing a man struggling and crying, while a white police officer digs his knee deeper into Floyd’s neck, the officer’s left hand slipped casually into his pocket. I watched in horror as the other police officer stood guard, protecting his fellow officer, while the person behind the camera screamed and pleaded with the officers to stop. I heard others begging for his life as George Floyd pleaded “I can’t breathe” over and over again.

The video went viral! Each time I watched the news, my heart cried. It is recorded thanks to cell-phone imaging and surveillance cameras and, because of the camera, we see history repeating itself. Just this past March, Breonna Taylor was killed in Kentucky; in February, Ahmaud Arbery’s death was recorded in Georgia, and not until weeks later did the national news media report his tragic death. COVID-19 killed 100,000 Americans, and their names appeared on the local news and some of their portraits were published in the newspapers. Activists, community members, students, first responders, essential workers, government and city officials, family members, and others have used the images to make change happen because of a history of injustices.

© and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

I started thinking about Black death well before the global pandemic and global lockdowns and measures of combating and coping that have become our everyday reality. I will never forget the photograph of the brutally beaten and swollen body of the young Emmett Till published in Jet magazine in 1955. Many young people experienced episodes of hostile confrontation with the police that intensified over the years because of social protests. Blacks were being killed, hosed, jailed, and subjected to unjust laws throughout the American landscape. Photographers witnessing both brutal and social assaults created a new visual consciousness for the American public, establishing a visual language of “testifying” about their individual and collective experience. On April 27, 1962, there was a shootout between the Los Angeles police and members of the Nation of Islam (NOI); Ronald Stokes, a member of the Nation of Islam, was killed. Fourteen Muslims were arrested; one was charged with assault with intent to kill and the others with assault and interference with police officers. A year later, Malcolm X investigated the incident and the trial. Noted photographer Gordon Parks remembered his photograph of Malcolm X holding the brutally beaten NOI member in this way:

I recall the night Malcolm spoke after this brother Stokes was killed in Los Angeles, and he was holding up a huge photo showing the autopsy with a bullet hole at [the] back of the head. He was angry then; he was dead angry. It was a huge rally. But he was never out of control. The press tried to project his militancy as wild, unthoughtful, and out of control. But Malcolm was always controlled, always thinking what to do in political arenas.

I share this history, as I am always mindful of the past because of visual culture. I value this history, even though I am distressed by it—even more so because Gordon Parks High School was destroyed by fire in St. Paul, Minnesota, this week.

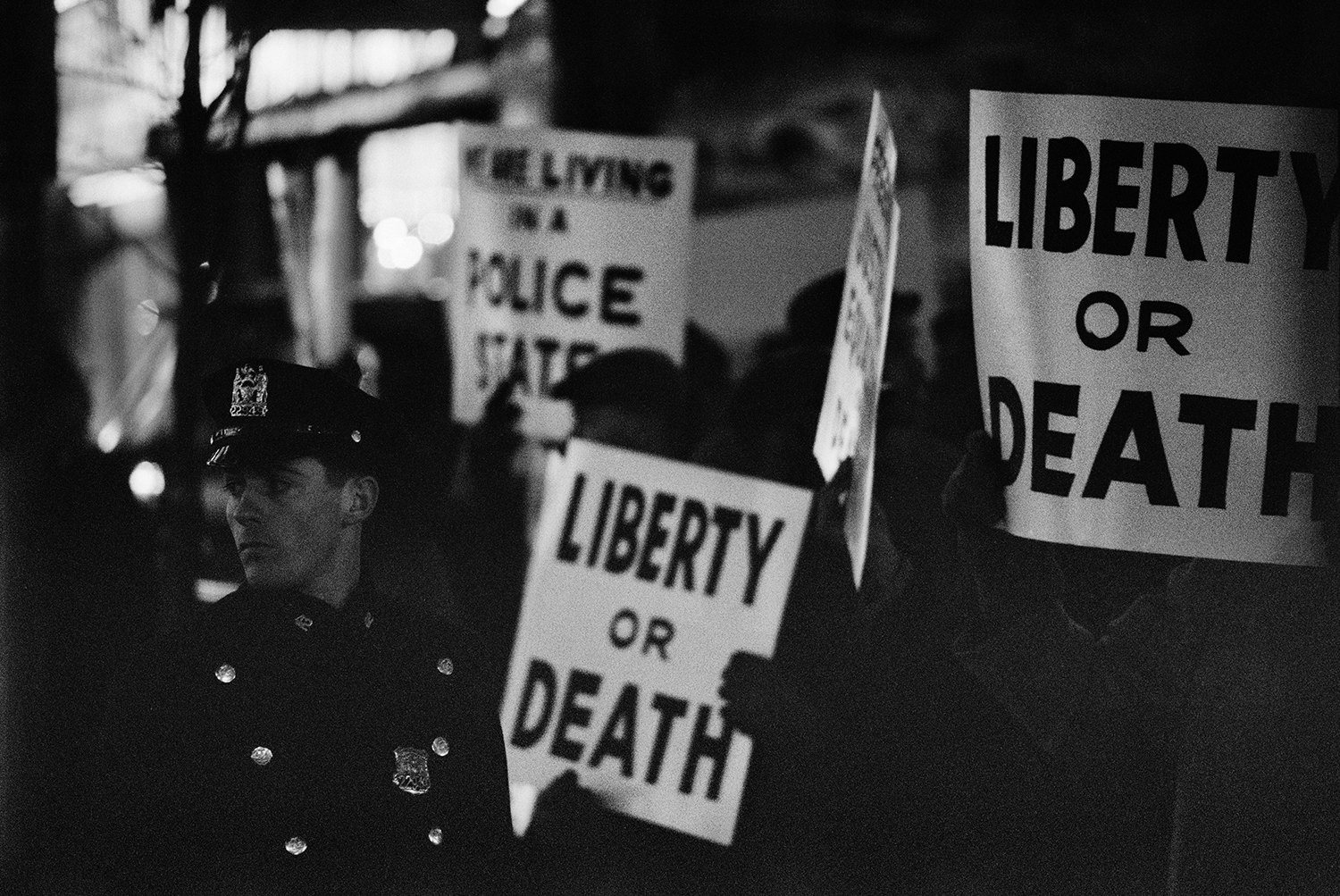

© and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

History!! James Baldwin said, “To accept one’s past—one’s history—is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it.” The last few months have confounded me for a variety of reasons, but perhaps most because Baldwin was meticulous as a writer and did not spare words, thus his use of the verbs learn and use in the above are clear iterations of this, of functionality. Learn to use art (image). And make history right. In 1987, Toni Morrison wrote in Beloved, “And O my people, out yonder, hear me they do not love your neck unnoosed and straight. So love your neck; put a hand on it, grace it, stroke it and hold it up.”

Collectively, we must continue to remember that photography and images can be both empowering and ominous; they can help us make changes to the laws as we struggle to find words for this painful moment. I am encouraged by our students’ activism as they photograph this charged moment, and at the same time, make photographs of the causes of inequities. I urge everyone to use this incredible energy to vote; to document injustices; to be encouraged by the voices of the people around this country telling this story globally and depicting the faces of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd on their face masks, T-shirts, signs, and murals; and to ensure that this will be the last time.

A version of this text originally appeared on New York University’s website as a letter to students.

Click here for further resources related to supporting Black lives.