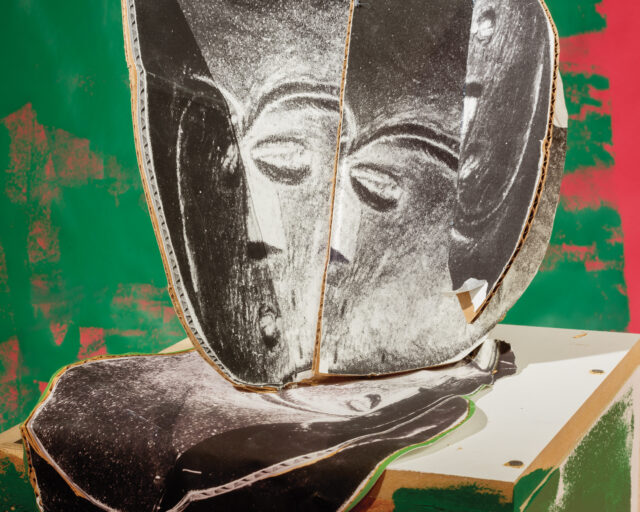

Black Is Beautiful

In the 1960s, Kwame Brathwaite’s fashion photographs sent a riveting message about Black culture and freedom.

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 228, “Elements of Style,” Fall 2017. See more of Brathwaite’s work in Black Is Beautiful (Aperture, 2019).

Everyone knows the phrase “Black is beautiful,” but very few have heard of the man who helped to popularize it. Brooklyn-born black photographer Kwame Brathwaite has lived most of his life behind the camera, devoted to capturing the lives of others on film. Spending much of the 1960s in his tiny darkroom in Harlem, he perfected a processing technique that made black skin pop in a photograph, with a life and energy as complex as that decade. Known by friends and comrades as the “Keeper of the Images,” Brathwaite has logged thousands of hours in the darkroom, dipping his fingers into harsh developing chemicals so often over the decades that the grooves of his fingertips have become worn. His labor reflects his deep commitment to black freedom and radical cultural production. With every dip, measurement of solution, and timing of exposure, Brathwaite styles blackness. His images, carefully calibrated to reflect a moment precisely, made black beautiful for those who lived in the 1960s, and continue to do so for a generation today who might only now be discovering his work.

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

I first stumbled upon Brathwaite’s photographs in 2009 at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. There I found a series of provocative images of black picketers taken at an August 1963 protest of a white-owned beauty supply store in Harlem called Wigs Parisian. The black women and men in the photographs carry placards that boldly declare: “We Don’t Want Any Congo Blondes!” and “He’s Got Straight Hair, but He’s Still an Ape!” Drawings of dark-complexioned women with large lips sporting blonde wigs and an ape with slicked hair dressed in a tuxedo accompany the texts. The photographs are riveting and unlike any that I had previously associated with the protests of the early 1960s, when slogans such as “Freedom now” and “One man, one vote” were rallying cries. They touch a sensitive nerve. They confront our collective feelings of pain and shame. Those feelings about our hair and bodies that we adopted in childhood and still fight to keep at bay. These piercing images, locked away in a small box in Harlem, represent a history that I had never learned in college or graduate school. I wanted to know: Who was this photographer? Who were these protestors? Google searches yielded little; Brathwaite seemed to exist only in the photography of the past and in minor quotes in black nationalist publications such as Muhammad Speaks and the Liberator. My countless email requests for an interview with Brathwaite went unanswered, until I was able to speak with him last winter for this article.

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

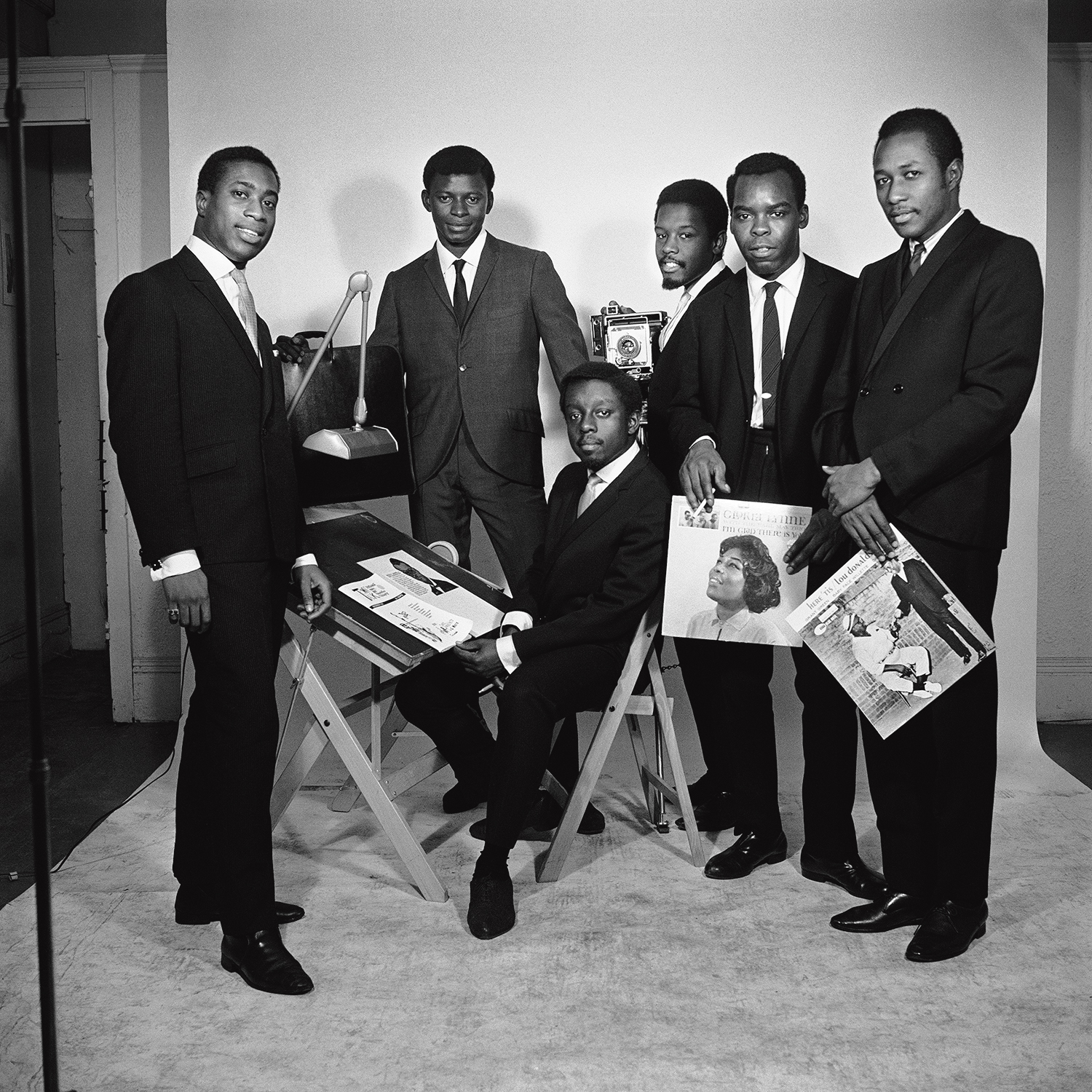

Brathwaite found photography through his love of the rollicking rhythms of hard bop jazz. In 1956, he and his teenaged friends, all recent graduates of the School of Industrial Art (now the High School of Art and Design) in Manhattan, formed the African Jazz-Art Society and Studios (AJASS), a radical collective of playwrights, graphic artists, dancers, and fashion designers. Jazz societies were common at this time, and AJASS modeled itself after the well-established Modern Jazz Society. They opted to use the then much less common word African, which made their group distinct and referenced their political leanings.

Years earlier, Brathwaite and his older brother Elombe Brath, a graphic artist, had heard activist Carlos Cooks espousing the politics of black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey: “Take back our land!” “Go back to Africa!” “Black is beautiful!” His message of black empowerment and economic independence resonated with the brothers, and they joined Cooks’s African Nationalist Pioneer Movement. “We weren’t fond of just being colored folks, being under the yoke of anybody else,” Brathwaite told me when I interviewed him. AJASS members were the “woke” set of their generation, calling themselves African and black when most people were still using the now passé colored or negro. In jazz, they found a similarly rebellious spirit, a music that communicated emotions that could not otherwise be articulated.

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

AJASS members spent most of their weekends promoting concerts at the legendary Club 845 on Prospect Avenue in the Bronx, the epicenter of the borough’s jazz scene, where they began booking rising stars like John Coltrane, Lee Morgan, and Philly Joe Jones. “We could pick some of the best musicians in the world,” Brathwaite recalls. “We’d have good, packed houses all the time.” One evening in 1956 Brathwaite strolled into the club, greeted customers perched at the bar, then headed toward the back of the venue and into the cavernous performance space, the sound intensifying as he neared the stage. One of his school friends was snapping pictures in the dimly lit club, and Brathwaite was astonished that he was not using a flash or any additional light source. Nothing. Brathwaite, the advertising-arts major who had never really worked with a camera, asked his friend, “How do you do that with no flash?” His friend’s professional camera and Kodak Tri-X film (the film that revolutionized photojournalism because of its speed and versatility) were far superior to the camera Brathwaite had received as a gift at graduation. “I couldn’t do what he was doing with that,” Brathwaite told me as he swatted the air in a dismissive gesture.

And just like that, Brathwaite was hooked. He used his earnings from the jazz shows to buy a professional camera and devoured every photography book he could find. Jazz set the rhythm for his photography, which became central to his artistic approach. “You want to get the feeling, the mood that you’re experiencing when they’re playing,” he explains. “That’s the thing. You want to capture that.” But translating the moody blue notes of jazz onto film is not a skill one can learn from a book; it is sensory knowledge that comes from an understanding of jazz culture—the syncopated rhythms, the elasticity of sound, the spirit of improvisation. The temperament of jazz is the lifeblood of Brathwaite’s work.

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

The new camera became young Brathwaite’s closest companion, kept within reach so he could take a snap whenever something intriguing crossed his line of sight. Most of his early images were from the Club 845 sets: jazzmen on their horns, spectators enthralled by the music. He also photographed the quiet intimacy of the musicians’ lives. “I’d go to Coltrane’s house at times. He would be playing the soprano sax in his kitchen with his T-shirt on. I got some shots,” Brathwaite told me. As the unofficial photographer of New York’s annual Marcus Garvey Day celebration, he quickly learned that photography required fearlessness. During the parade, Brathwaite would bend and contort his lithe body, often throwing himself into the crowd in order to document the extravagance and pageantry of the lively event.

As Brathwaite perfected his camera skills, taking hundreds of photographs each week in those early years, the movement for black freedom was erupting on the Harlem and Bronx streets around him, as much as it was in the American South. The federal government had overturned “separate but equal,” but black Americans like Brathwaite and his peers still felt the cold fear and unease of stepping too close to the invisible line of Jim Crow segregation. Photography was the insurgent technology through which everyday people and professional photojournalists alike captured the wild violence of police billy clubs and the quiet threat of “Whites only” signs in shop windows from downtown Manhattan to Montgomery, Alabama.

The “Black is beautiful” movement really started to coalesce in and around Harlem in late 1963, after the Wigs Parisian protest. “That’s when we started promoting ‘Black is beautiful’ even more. We had entertainment with fashion shows and concerts and stuff like that, which made us very popular in the community,” Brathwaite said. They began using “Black is beautiful” and other slogans such as “Think black” and “Buy black” on event flyers and other ephemera.

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

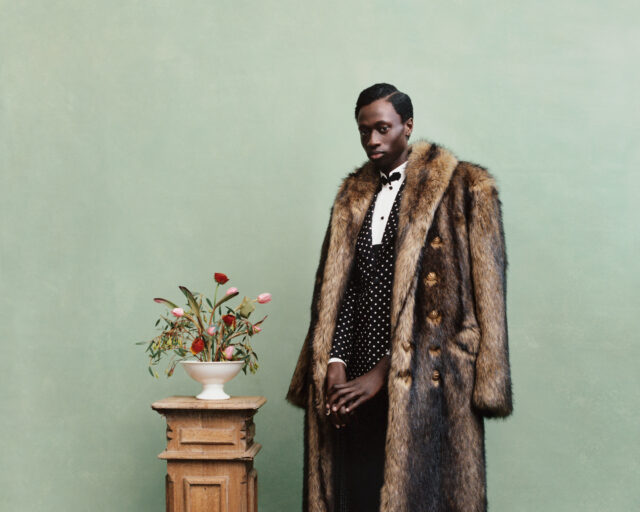

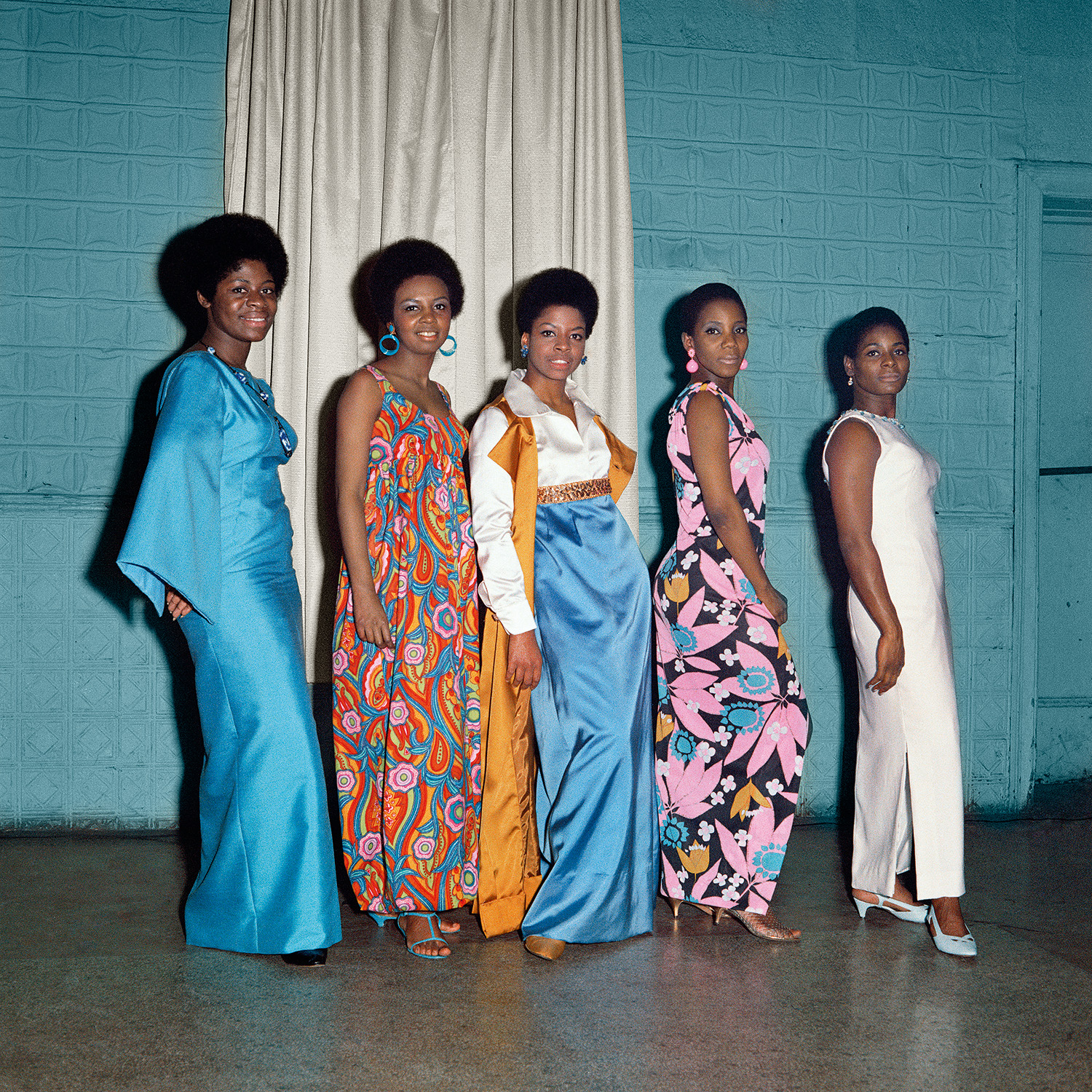

Brathwaite wore his “Keeper of the Images” title with great pride and conviction, allowing his brother to take the lead as the public voice of their movement. Yet, the mostly male group realized that beauty and body issues affected black women differently. “We said, ‘We’ve got to do something to make the women feel proud of their hair, proud of their blackness,’” Brathwaite explained to me. In order to truly communicate why black was inherently beautiful, they needed women at the helm. With the help of a well-connected AJASS member, Jimmy Abu, they began recruiting teenage and young adult women to model in a community-based fashion show. They named the group Grandassa, drawing from the word Grandassaland, which Carlos Cooks used to describe the African continent. The original models had deep chocolate skin, full lips and noses, and wore their hair in “natural” styles that highlighted their kinky textures.

The Grandassa models dazzled the crowd of mostly black folks from Harlem and the surrounding neighborhoods who assembled at the Purple Manor on January 28, 1962, for Naturally ’62: The Original African Coiffure and Fashion Extravaganza Designed to Restore Our Racial Pride and Standards. Actor Gus Williams served as host alongside jazz singer and activist Abbey Lincoln, while her husband, jazz drummer Max Roach, led the house band. The models sashayed across the makeshift catwalk in vibrant dresses, skirts, and sophisticated blouses constructed from fabrics with intricate prints. Each woman accessorized her look with large hoop earrings, chunky bracelets, and kitten-heeled mules and sandals.

The event was a smash. AJASS soon produced more shows, eventually making Naturally an annual event. “We started picking up designers, black fashion designers,” Brathwaite said, noting that Carolee Prince, who created headdresses for famed singer Nina Simone, also showcased her original pieces in the Naturally shows.

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Brathwaite and his crew realized they were now at the center of a brewing national conversation on colorism and race pride within the black community. The Grandassa models were not simply countering the images of pale and frail British models such as Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton who appeared in mainstream U.S. publications. They were also challenging the ubiquitous presence of lighter-complexioned, straight-haired black models in black- owned publications such as Ebony. “There was lots of controversy because we were protesting how, in Ebony magazine, you couldn’t find an ebony girl,” Brathwaite told me.

Spurred on by the cultural zeitgeist of the moment, Brathwaite transformed AJASS from a band of creative teens into a group of businessmen and -women who could “sell” their vision of blackness to an international audience. In 1964, they signed a lease on a studio space next to the Apollo Theater. Brathwaite and Brath produced “Black is beautiful” ephemera—as well as several Blue Note Records album covers—and charged a sitting fee to photograph local women and men. Later, they operated a café-style meeting space called Grandassa Land, on Seventh Avenue between 135th and 136th Streets, where they hosted poetry nights and plays organized by the AJASS Repertory Theatre. Lincoln and Roach introduced them to club owners in the Midwest who invited AJASS to present Naturally shows in Chicago and Detroit. Images of the stylish Grandassa models appeared in black publications in the United States, Britain, Nigeria, and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

The popularity of Grandassa and AJASS made Brathwaite a sought-after photographer for international magazines. His photographs of megastars such as Stevie Wonder, Muhammad Ali, and Sly Stone were published in Britain’s Ad Lib and Blues & Soul magazines, as well as in publications in Japan. With those early paychecks—much larger than the meager sitting fees he charged neighbors in Harlem—Brathwaite upgraded his equipment and traveled the world. He had encounters that a boy from the Bronx, whose only taste of the international had been his mother’s Caribbean coconut bread, could have only dreamed of.

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Naturally shows became less frequent as the 1960s drew to a close. Brathwaite and Brath delved deeper into pan-Africanist activism, and they traveled extensively across the African continent, working alongside activists in Ghana, Nigeria, Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt. Meanwhile, the catchy slogan “Black is beautiful” continued to spread and was used to sell everything from hair-care products and T-shirts to alcohol and cigarettes. The two brothers had helped to usher in this moment, making black nationalism artful and accessible to everyday black folks. But the brothers’ absence from the political, social, and artistic scene in the United States, and the ubiquity of soul music and black power imagery in the early 1970s, meant that most people never came to know them, AJASS, Grandassa, or the vibrant history of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance, of which they were at the center. Brathwaite’s photographs, which provide much-needed texture to our understanding of the black freedom movement, never became part of the movement’s visual canon. Instead, his images found a home in the Schomburg Center in Harlem, not far from where the AJASS studio was located, where they lay in wait for an eager researcher to access them and understand their significance. There were no retrospectives, no splashy write-ups.

And Brathwaite was fine with this. He never pursued photography for the accolades. He enjoyed the quiet life outside of the spotlight. Elombe Brath died in 2014, after suffering a series of debilitating strokes. The loss upended Brathwaite’s world. His brother was always the voice, the one who could galvanize the crowd with his booming speeches. With his passing, and that of most others in their collective, Brathwaite realized that he was not only the “Keeper of the Images”; he was now the keeper of the stories, too. If he didn’t share this history, it would be lost to time. At seventy-nine years old, Brathwaite is now telling the tale of how he—the son of West Indian immigrants—and a crew of black teens from the Bronx styled the world.