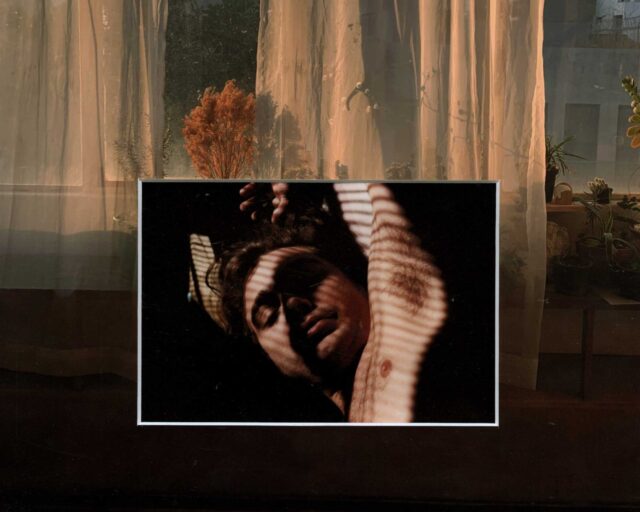

Muge, The man doing the laundry, 2006, from the series Going Home

Muge’s first memory of the Three Gorges Dam is from 1999, five years after construction began. He and his family were taking a trip to Yunyang, a county along China’s mighty Yangtze River so rich in vistas it’s known as the “Bright Pearl of Chongqing.” They were traveling there to get bulk items for their home in Chongqing’s mountainous Wuxi County, an eighty-nine-mile journey through soaring peaks and lush valleys. It’s a frequent trip Muge took during his childhood; a fond memory turned painful when he arrived in Yunyang that year to find the place demolished.

“I lost my beautiful memories,” Muge said recently, likening the feeling of seeing the past disappear to amnesia. “Although you know there is a past, you can’t witness it for yourself.”

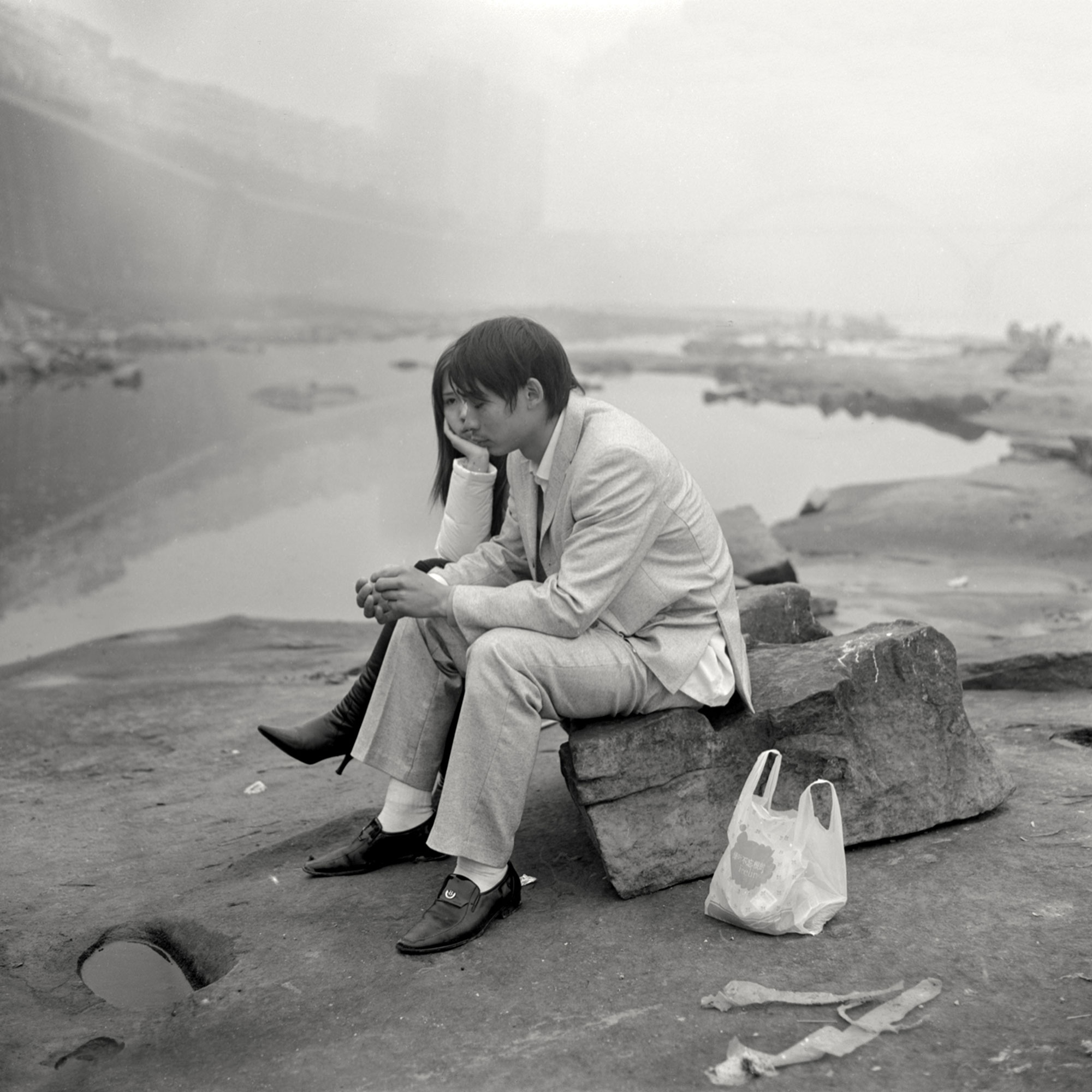

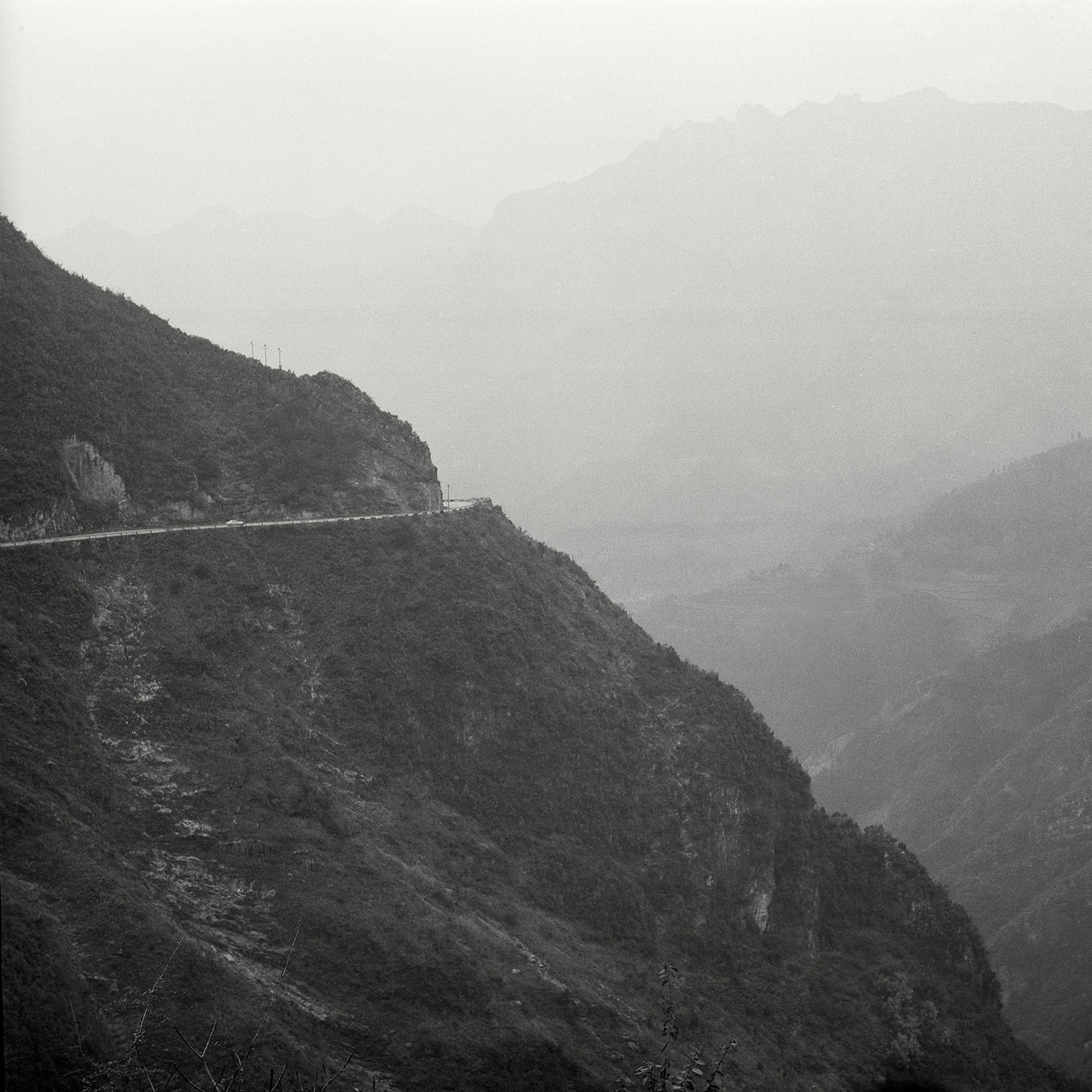

Going Home, begun in 2004, is an ongoing, nearly two-decade-long, endeavor to recover his memory, a monochrome series that captures the yearning of over a million people displaced from their homes along the Yangtze River—including Yunyang—caused by the construction of the six-hundred-foot-tall Three Gorges Dam, completed in the mid-2000s. In the years it took to build, the world’s largest hydroelectric dam wrought ecological and societal devastation. The dam swelled the Yangtze for three hundred miles upstream, creating an inland reservoir that submerged, or prompted the demolition of, hundreds of riverside towns and villages in the area where Muge grew up. Through photographs of dirt roads, rubbled shores, and abandoned cities, Muge chronicles a melancholy, spiritual journey in search of a home that is no longer there.

“In the end, you find nothing,” he says. “We wait for better living in desperation.”

Born in 1979 and raised in rural Chongqing, Muge grew up fantasizing about what lay beyond. Travel in those days was slow and crude. Whenever he wanted to do something or go somewhere, it was a journey through the natural world. When his family decided to get a television set when he was seven years old, it was a two-day expedition. “Every trip [was] a new life,” he says. The slowness of travel from Muge’s childhood sets the pace for Going Home. “I am obsessed with the state of being on the road,” he says. Every seemingly trivial detail—from the condition of the road to the majestic landscapes—is a glimpse into his “inner core.”

Because he grew up surrounded by government propaganda, much of Muge’s visual inspiration came later, while he was studying at Sichuan Normal University in Chengdu, where he earned a degree in broadcasting and television directing. There, he was introduced to the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, Jean-Luc Godard, Kenji Mizoguchi, and Yasujiro Ozu. He also discovered Peter Henry Emerson, Minor White, and Walker Evans, traces of whom are especially visible in his photogravuresque landscapes: epic, mystic, and lonely. In his later travels, Muge picked up his alias. Born Huang Rong, Muge’s friends coined his nickname after traveling to Tibet, where they learned that muge means “wild man,” which his friends jokingly called him because he moves so fast. (In Mongolian, muge means “rising sun.”)

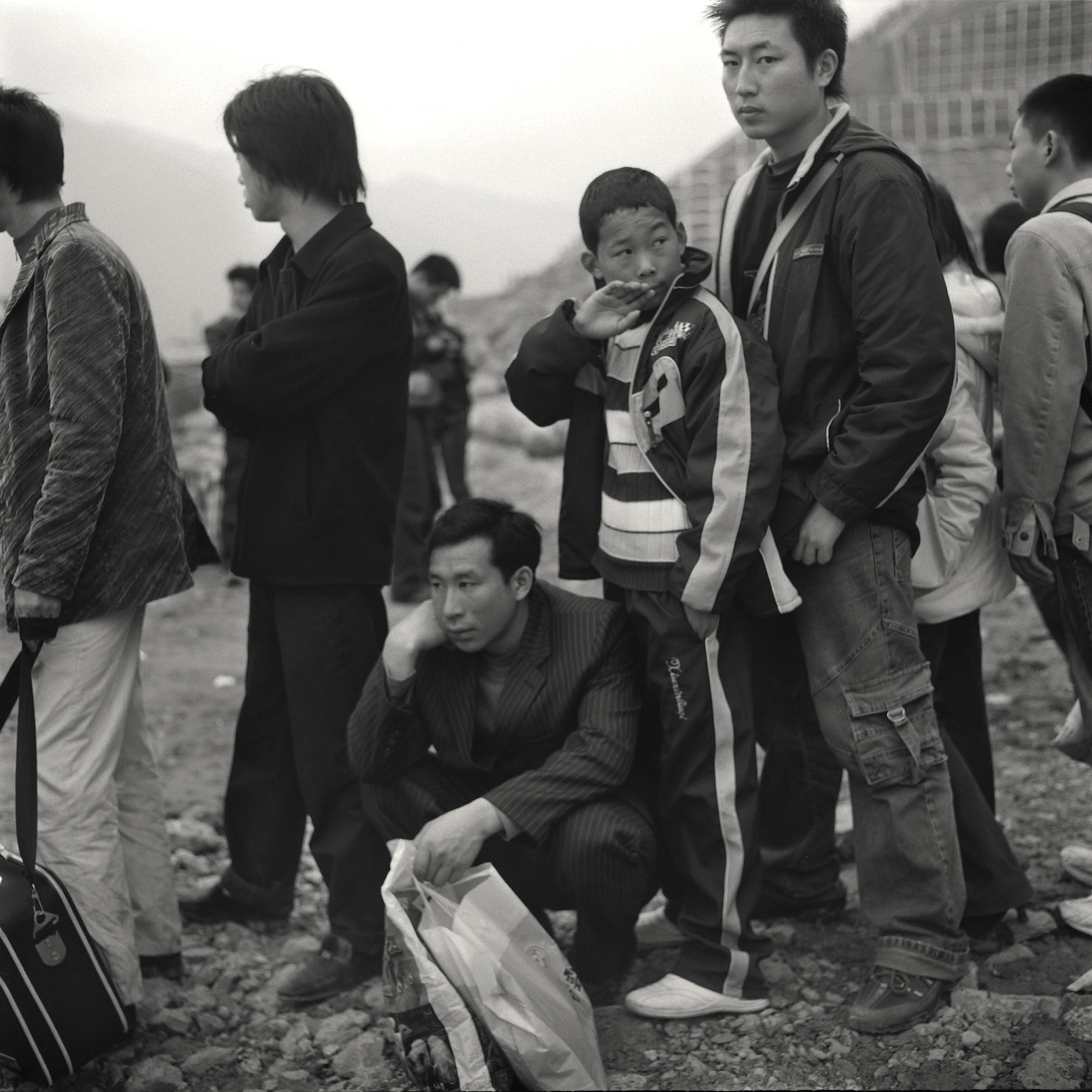

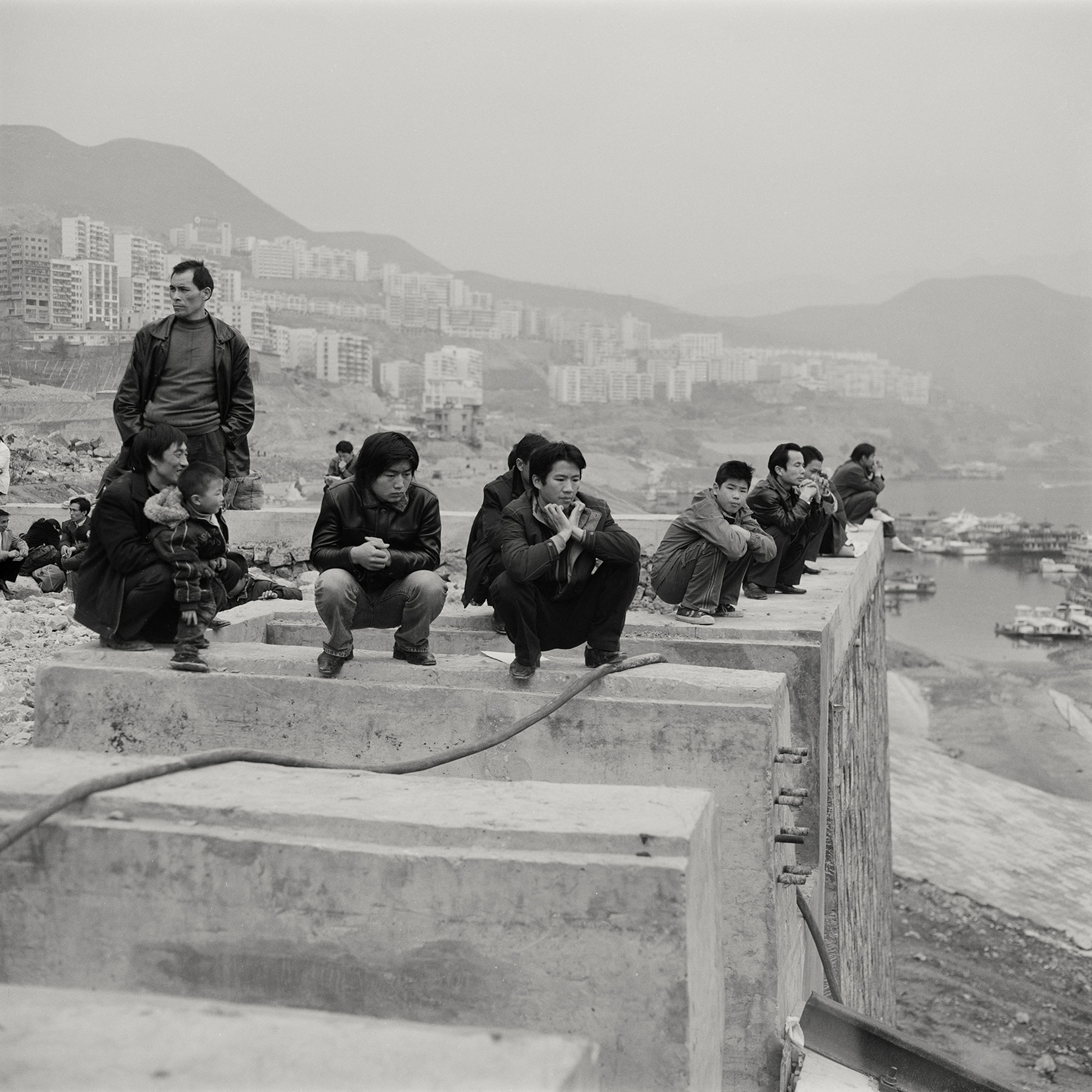

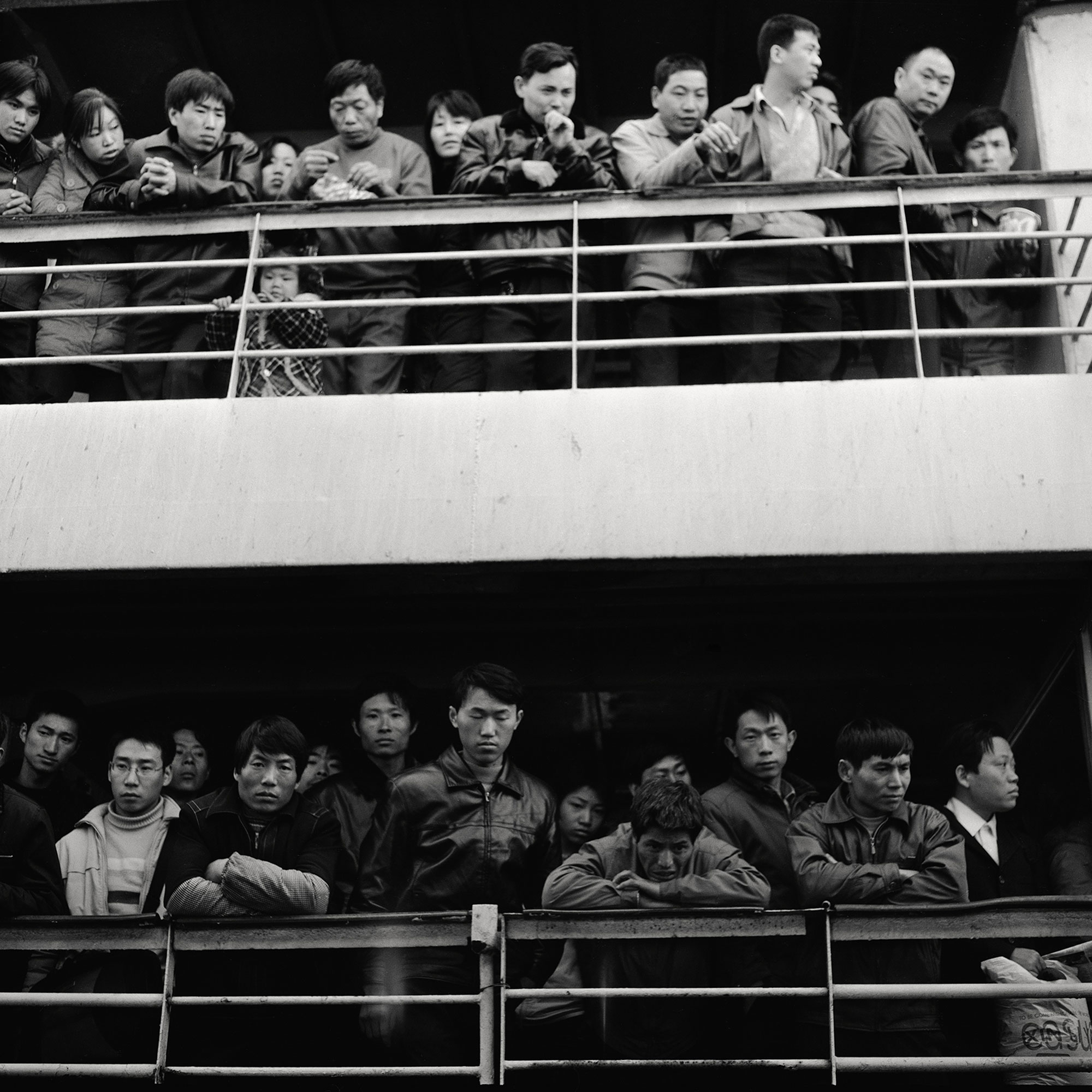

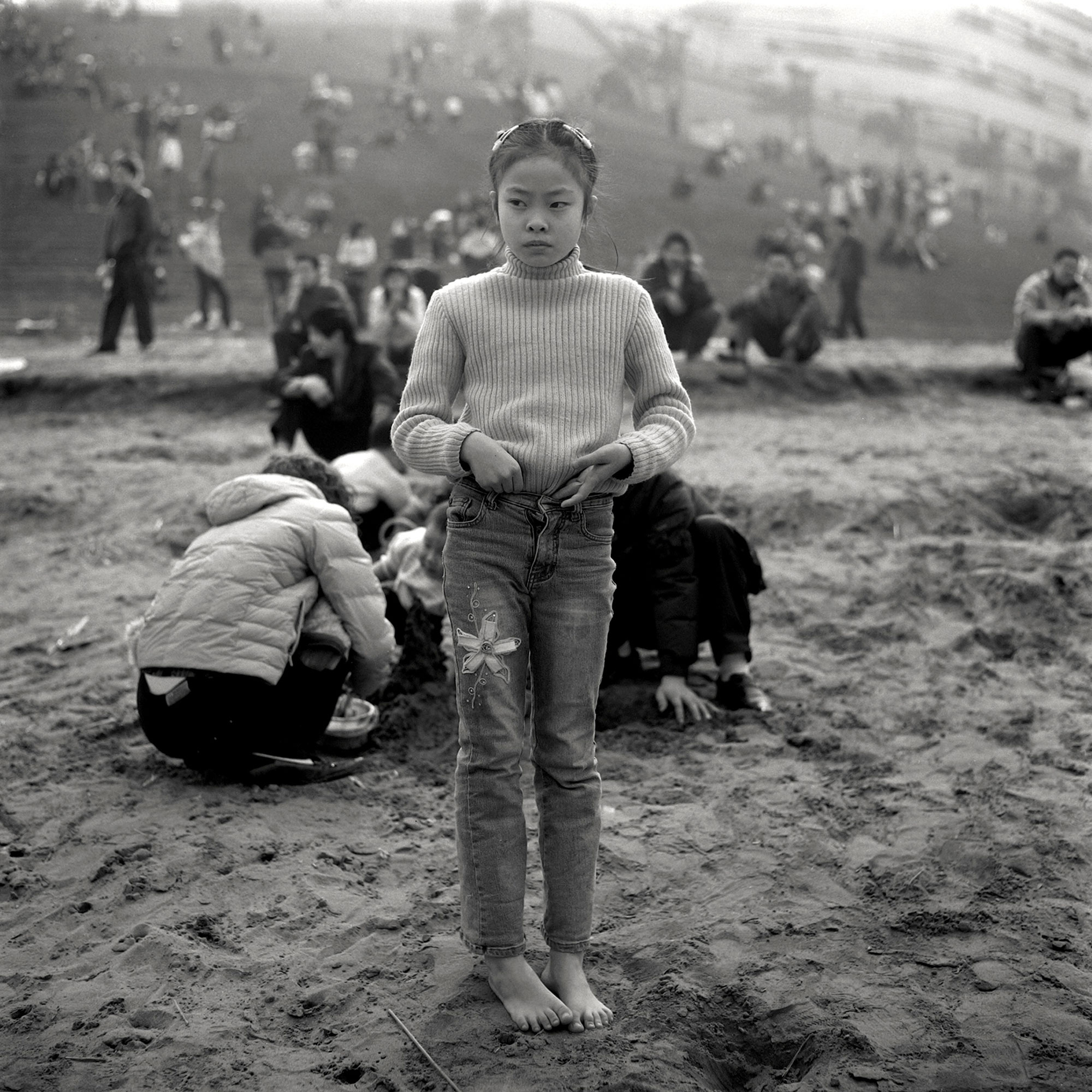

In the wake of the Three Gorges Dam, Going Home becomes more a wandering than a voyage. The expressions of Muge’s subjects—strangers, families, passengers, and migrant workers—are ones of loss and ache, unsure of what the future holds. Some squat along the cement shores of emptied cities waiting for a ferry to arrive. A couple burns a fire in a pile of rubble. Pollution or fog cloaks every sky. Mattresses pile up. A woman naps on an abandoned bunk bed along the river. Construction cranes loom. A policeman crouches in grassland. One man, standing atop a hill of rubble, looks up at a derelict home, looming like a steeple.

“The images are full of collisions between childhood memories and dramatic changes in reality,” says Muge.

While there is much to be said about China as a rising superpower, Muge’s photography was not created for that arena. To be sure, Muge’s subjects and their experiences are the direct result of China’s rapid economic development. But his intent is neither to comment on China’s macrostate nor to convey his personal feelings. Instead, he aims to “[step] in between,” he says, capturing the spirit of people caught in the nation’s slipstream.

“He’s somebody who’s very curious about people and likes to pay attention to their rhythms, patterns, and personalities,” says Xuan Juliana Wang, a Chinese-born American writer who met Muge in Chengdu, where he is currently based. With Going Home, the aim, above all, is to understand the dirt-level intimacy and complexity of people’s everyday lives. “You can never know about a place or about a people unless you visit it on the ground,” Wang says. “His work is after that.”

All photographs courtesy the artist. Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.