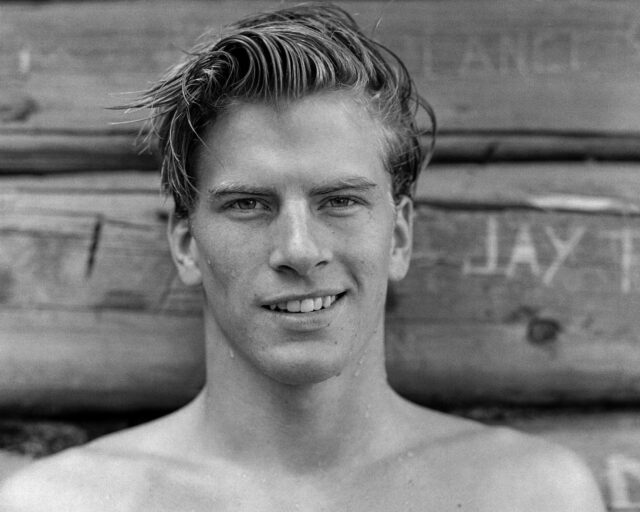

223, JinJing on the Couch, 2016

If you let him, 223 will come over to your place, open your fridge, rummage through your closet, and inspect your bedroom on a search for props he can use for an impromptu photo shoot. His friends have grown accustomed to his ever-present camera. Taking photographs has become second nature. “Some people, when I meet them, I immediately want to take their photograph,” he says. “Others, I’ll know for years, yet it never occurs to me to do that. I really can’t explain why. It’s just a feeling, a connection between us.”

Lin Zhipeng, the photographer known as 223, named himself after the lovelorn Hong Kong police officer in Wong Kar-wai’s 1994 film Chungking Express. Born in Shantou, China, in 1979, 223 spent his childhood on an army base in Fujian, eventually going to college and working in Guangzhou before drifting to Beijing, where he still lives today. He tells me has had no formal training in photography or obvious early influences in the arts. He’s never been someone who makes plans: “I make impulsive decisions. I take trips without preparation. I do that in my life, and I do that in my work.”

223’s images act as memory, a cadenced record of a life searching for things that intrigue him. “When I open any photograph I’ve taken, I am reawakened to everything happening at that very moment,” he says. He likes to be surprised, to find the numerous frequencies of existence no matter how mundane. A portrait might appear as a romantic overture, but then there is a turn. His point of view is set to the beautiful as well as to the grotesque, the ordinary, and the obscene.

223 captures friends kissing their lovers, running into the darkness, and eating noodles side by side with their heads cocked. An ex-boyfriend appears on a secondhand sofa, with the fallen leaves of their houseplant thrown at him. All easy gestures, aching with seemingly interminable youth. Then there is a black-and-white portrait of his friend, a young gay man. The photograph was taken in 2009. The following year, the friend committed suicide, and 223 wouldn’t find out for quite some time. “What I have is his photograph. I don’t tell his story often, only if people ask,” he says.

These days, 223 wants to live a quiet life and do as he pleases. “I am looking at the world with a sense of peace and serenity,” he says. “As I get older, I can feel my heart growing bigger and bigger. I am not trying to become emotional about every little thing.” If you follow his work, you will find that the same people reappear over fifteen years. He photographs some friends every time he sees them. One woman is first depicted as a teenager, but in a later series she is nearing middle age. People move, from Beijing to Shanghai or to the United States, and appear anew with gray hair and wrinkles around their eyes. “When I look at photographs from five, ten years ago, I can trace the small changes,” he says. “Some lovers have broken up, others have stayed together, and that will make me feel this immense sadness or joy for them. That is what I cherish most.”

All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.