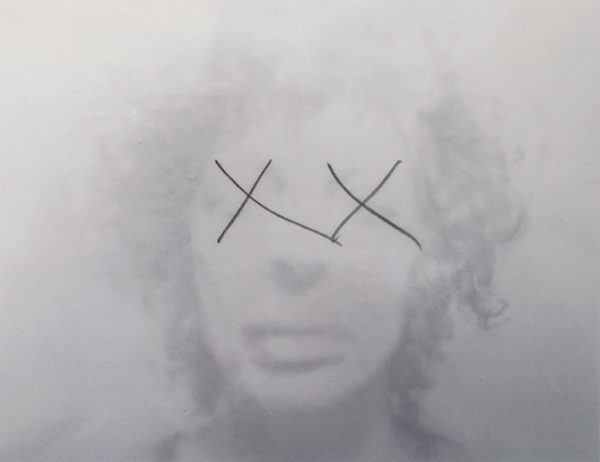

Barbara Ess, Peekaboo, 2014

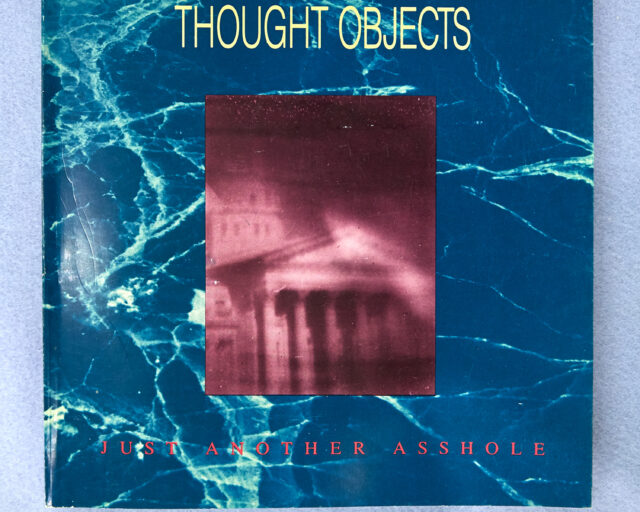

“There’s something very odd about trying to stop the world,” Barbara Ess says. Ess began her career not as a photographer, but as an experimental filmmaker and musician, engaging with mediums that embrace time rather than trying to stop it. While participating in international collectives and film festivals, Ess began using single-frame stop-motion cameras to create films, which she then turned into zines. A fresh dedication to photography was born as she then began self-publishing books featuring isolated still images such as This Happened Yesterday (1979) and Human Life (1979). Ess became fascinated with the divisions between movement, stillness, and sound.

Ess is also interested in the distance a camera creates and what viewing life from afar accomplishes, or as she describes, the chasm between self and other, the “in-here” and “out-there.” She has tackled this subject in past work, most notably in the book I Am Not This Body (1991), published by Aperture. Someone to Watch Over Me, recently on view at Magenta Plains in New York, features work made over the past nine years that explores themes of distance, subjectivity, and mediation. (Ess was my teacher when I was a student at Bard College.) Spanning both floors of the gallery, the exhibition included seventeen photographs, two videos, and a sound piece. Three series—Surveillance, Remote, and Border—employ photographs captured from live-stream footage; another body of work on view, Shut-In (2018–19), was created while Ess was isolated in her apartment for a month with bronchitis.

Someone to Watch Over Me explores the divide between where you are and where you are not—what it’s like to witness events outside one’s window or one thousand miles away. “I asked someone once, how is the world where you are not? You never know,” Ess told me when we spoke recently. “When you walk out of a room, what’s it like when you’re not there?” In Someone to Watch Over Me, Ess captures images in unorthodox ways: placing a small telescope before a lens, using a broken point-and-shoot camera and taking screenshots from her computer. Each method of image-making derives from a source of mediation, distancing Ess further and further from the actual world in which her subjects reside.

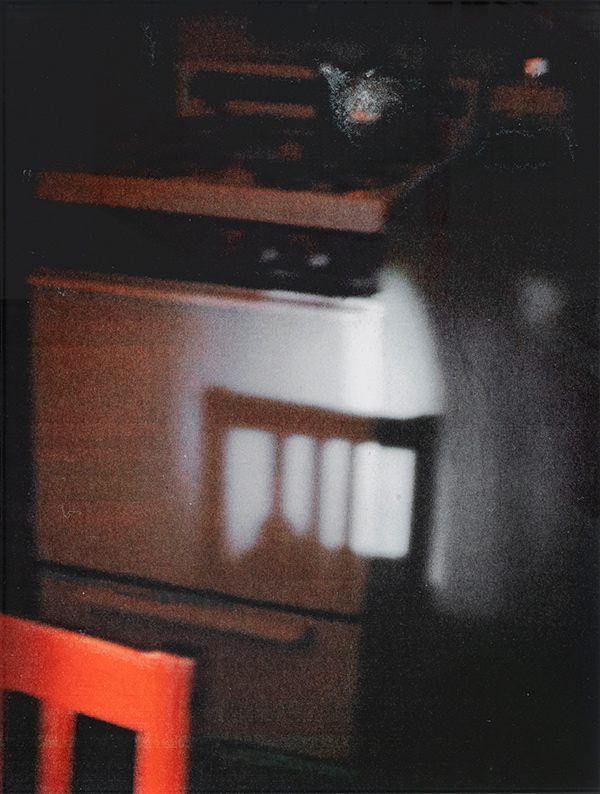

In Shut-In, which was installed in the basement level of the gallery along with several images taken from traffic and weather cameras, Ess depicts details of her apartment and the view into neighbors’ windows, only to show that their blinds are drawn. Vases and air conditioning units become the focus, obstructing viewers from gaining entrance into their lives, and drawing the attention back to Ess. These are the only photographs directly representative of the artist’s personal life. Ess created the images using a standard inkjet printer, drew on them with crayons to alter the texture, rescanned them, and then printed them large. Even Ess’s still images feel as if they are moving. The lo-fi quality vibrates in its graininess, producing the same stir-crazy feeling one might experience after a month of being stuck inside an apartment.

To Ess, the thematic center of the show was in two photographs, most visible when exiting the gallery, Peekaboo (See Not Be Seen, 2014/2019) and Attenti al Cane (Cyan Dog) (2007). Peekaboo, a silvery self-portrait of Ess, was the only image in the exhibition depicting a full face, yet Ess has drawn two Xs marking out her eyes, negating the ability to see her image fully. The two black Xs are both a punk gesture, as well as a reference to Rosalind Franklin’s photograph of DNA, Photo 51 (1952), according to Ess. Here, she is both fact and fiction, present and not, captured in a fog. Sitting below Peekaboo is Attenti Al Cane, or “Beware of Dog” in Italian, a blurred image of a German shepherd. The dog “acts as both a protector as well as some kind of surveillance, a watch dog, a seeing eye dog,” Ess explains. The original function of the dog is buried in the layers of distance from the dog itself. “This separation gives you some emotional and mental distance, from your subject, to roll around in your mind and your eye,” she says.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Magenta Plains, New York

Back on first floor were images from the Surveillance and Border series, all pulled from livestream footage on the U.S.–Mexico border. To have access to cameras monitoring the border along Texas, Ess signed up as a “Deputy Sheriff,” where she was tasked with reporting suspicious behavior. The resulting video from a heat-sensitive camera, Crossing (2011), is shockingly pastoral in comparison to a neighboring image, a sign warning passersby of an electric fence. The camera pans across trees blowing in the wind, and down a river, catching a pack of galloping horses, all while following a man as he tries and ultimately succeeds in entering the United States by crossing the Rio Grande. While Ess didn’t have any agency in what she saw, aside from what she decided to record, the video embraces the beauty in the mundane, of watching and waiting from a distance. It’s easy to imagine that someone who would sign up to survey the border would be eager to report illegal activity. Instead, Ess found interest in the forms of the water and the trees, and the deceptively small narratives of the people she encountered.

Someone to Watch Over Me was on view at Magenta Plains, New York, April 7–May 12, 2019.