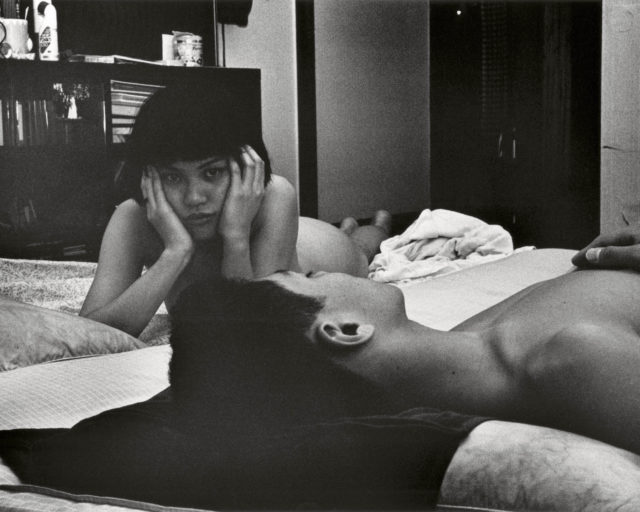

Bruce Jackson: On the Inside

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

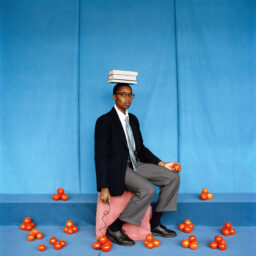

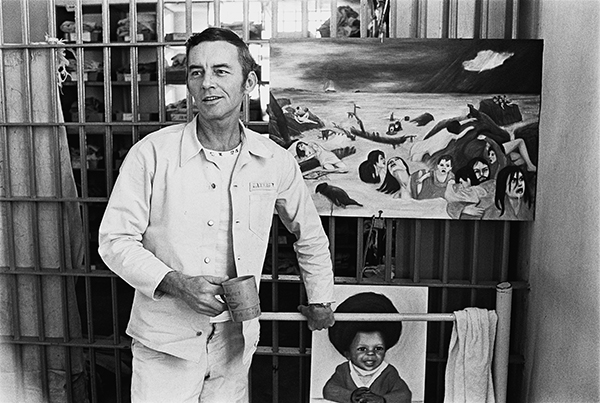

Among other things, the American prison system is designed to keep a purportedly disagreeable or disposable portion of the population out of sight and out of mind. The same walls that keep prisoners in are intended to keep prying eyes out. The secret lives of prisoners—their living conditions, their social systems, their codes—are, in the free world, virtually invisible, and, therefore, unknowable. Breaking through these barriers, folklorist and photographer Bruce Jackson has, for over fifty years, tried to get inside the penitentiary walls to tape-record, film, and photograph inmates, not only to document their unique cultural forms and social microcosms, but also to make a clamorous case for prison reform and prisoners’ rights.

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

Like many documentary photographers of the 1960s and 1970s, Jackson developed a unique approach to infiltrating and re-presenting otherwise unknown aspects of seemingly impenetrable and forbidding subcultures. Between 1964 and 1979, he compiled extensive studies of the social behavior of prisoners in Texas and Arkansas state prisons, and his research was presented in dozens of scholarly books, essays, films, and audio recordings. In 1964, while a visiting fellow at Harvard University, he first traveled to Ramsey prison farm, near Rosharon, south of Houston; it was Freedom Summer, a period of especially high racial tension in the South. Jackson’s goal—as noted in his 1965 text “Prison Folklore”—was to record “the ways of prison life, the factors that make for an independent world: the language and code, the stories and sayings, and, sometimes, the songs.” Following in the footsteps of early folk song collectors like Alan Lomax and Paul Oliver, Jackson was gathering the remnants of a rapidly disappearing African cultural tradition lingering in the diaspora in the forms of oral histories, toasts, spirituals, gospel music, blues, and work songs.

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

The archipelago of southern prison farms that Jackson encountered in East Texas from 1964 to 1967 consisted of vast tracts of forests and farmlands, often located on the sites of former slave plantations. Under the watchful eyes of mounted prison guards, segregated work details of inmates, in matching white uniforms, labored from dawn to darkness building roads and levees, picking cotton and tobacco, planting bottomlands and felling trees, swinging axes in unison to the chants of traditional work songs. Cadenced work songs were a survival technique, intended to synchronize the prisoners’ labor, pace them under the scalding sun, and keep slower workers from falling behind. In the free world such music had been forced away or co-opted by commercial interest, but in the isolated prison work crews and chain gangs this anachronistic music survived. “I was interested in the black convict work songs,” Jackson recalled, “because they go back to a slavery-time musical tradition which in turn goes back to an African musical tradition. It’s a pure, unbroken line of musical performance and style, and the way music and physical labor integrated with one another.”

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

In March 1966, Jackson joined with folk singer Pete Seeger and his family to film the last vestiges of African American work songs at Ellis prison farm, near Huntsville, Texas. The mesmerizing thirty-minute, black-and-white documentary film they produced, Afro-American Work Songs in a Texas Prison, records the chants and the rhythmic chopping, with very little narration. It’s the only known film record of a tradition that, by the following year, had literally vanished.

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

In this context, Jackson began taking photographs, initially as notes or aides-mémoire, and later to illustrate his many publications. Jackson was interested in capturing whatever elements of prison folklife could be recorded, using whatever documentary instruments were necessary to gather this information as thoroughly as possible. According to Jackson, “Documentary work entails a responsibility to an external reality. For me, that external reality is broad and complex. Human experience is not one thing, it is everything: it is what you have for breakfast, what you wear, what you make, and the stories you tell. So, what I was trying to do was to use as many instruments as I could to look at and to preserve as many aspects of that world as I could, to let other people see what I saw. Photography was equivalent to my tape recorder.” Jackson’s photographs formed a crucial part of the research for his several classic books on prison life, including In the Life: Versions of the Criminal Experience (1972), Wake Up Dead Man: Afro-American Worksongs from Texas Prisons (1972), and “Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me”: Narrative Poetry from Black Oral Tradition (1974).

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

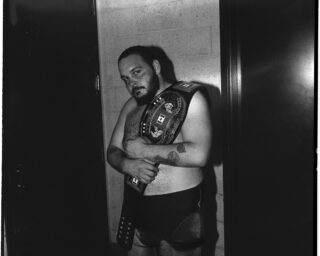

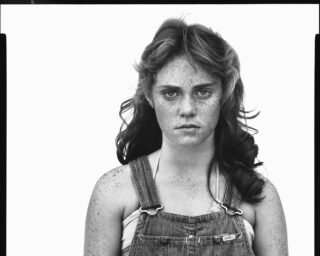

True to his training as a folklorist, Jackson tended to be more practical than poetic about his photography, saying, “What I wanted in my photographs was the sense of what it was like if you were standing where I was standing.” Jackson’s photographs from the antiquated East Texas prisons meticulously catalog the various components of the bureaucratic penal system: the entry, or sally port; the chain-link and razor-wire perimeter; the warden’s office, with its boar’s head decor; the uniformed guards, mounted on horseback with rifles; the prison yard, where inmates are forced to strip down; and the endless parched fields, where the prisoners work. A retrospective volume of Jackson’s photographs, Inside the Wire: Photographs from Texas and Arkansas (2013), reproduces these brutal pictures with merciless fidelity. And they are astonishing, in part, because they seem so alien and anachronistic.

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

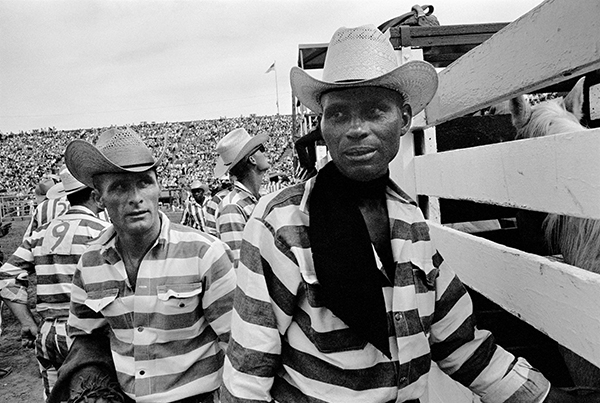

These stark black-and-white photographs capture the primitive social conditions and enforced slavery-like labor of a not-so-distant version of criminal justice. They show legions of prisoners with raised shovels and hoes marching to work in the fields; they show uniformed guards with rifles monitoring the workers from high on horseback; they show inmates in striped prison costumes performing at a local rodeo; and they show inmates at ease in anonymous and poorly lit prison lunchrooms, confronting boredom. Pictures of paunchy white prison guards sipping iced tea while a field of hunched-over, white-suited African American prisoners pick cotton are not only images of a bizarre cultural remnant of the Old South, but also are records of the deliberately dehumanizing, almost medieval, caste system that survived in American prisons as late as the 1970s.

To continue reading, buy Aperture, Issue 230 “Prison Nation,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.