Don McCullin Doesn't Want You to Look Away

Don McCullin, The Battle for the City of Hue, South Vietnam, US Marine Inside Civilian House, 1968

© the artist

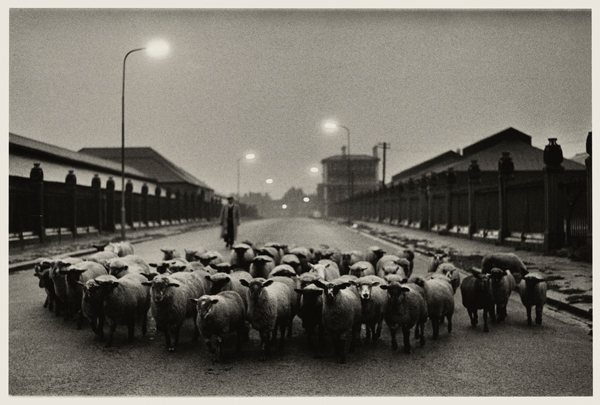

In the first of the ten galleries that make up the staggering retrospective Don McCullin, currently on view at Tate Britain in London, hangs a prescient photograph taken by McCullin in 1965, entitled Sheep Going to the Slaughter House, early morning, near Caledonian Road, London. A gloomy gray haze hangs heavily in the dawn air as a shadowy figure in a long coat and flatcap marches a tightly packed herd of sheep, more than forty strong, along a wide, straight road to their deaths.

Seen through the eyes of McCullin, who grew up among the ruins of Blitz-scarred north London in the early 1940s, and would later photograph for the Observer and The Sunday Times Magazine, what might have otherwise been depicted in previous centuries as a rather quaint and pastoral image of British shepherding life is infused with a haunting sense of postwar horror. Thick black fences, buzzing streetlamps, elongated factory-like buildings, and blocky towering structures line the street with an impeccable, cold regularity, inevitably evoking the startlingly bleak pictures of concentration camps taken only twenty years earlier, and which have resounded within our collective unconscious ever since.

Don McCullin, Sheep Going to the Slaughter House, early morning, near Caledonian Road, London, 1965

© the artist

In the making of the photograph McCullin firmly positioned himself directly in the herd’s path, situating the picture and the viewer precisely between his subjects’ immediate present and the brutal fate that soon awaits them, unflinchingly recording their last living moments: some bow their heads in resignation, others look anxiously into the distance, and, most distressingly, several of them look us straight in the eye.

McCullin’s exhibition is densely hung in a relatively linear fashion with his own handmade gelatin-silver prints, and proceeds chronologically through a remarkably diverse career that spans more than sixty years—from his documentation of the teddy boy gangs that loitered in the streets of his childhood neighborhood in the 1950s, to anti-fascist protesters in Trafalgar Square and the building of the Berlin Wall in the early 1960s.

Don McCullin, Protester, Cuban Missile Crisis, Whitehall, London, 1962

© the artist

He covered wars waged in Cyprus, Biafra, the Republic of the Congo, Vietnam, and Cambodia in the late 1960s and early ’70s; the Troubles in Northern Ireland; the rise of homelessness in London’s East End; the plight of industrial cities in the north of England throughout the 1970s; the war zones of Beirut, Bangladesh, and Iraq in the 1980s and ’90s; the AIDS pandemic in Africa in the early 2000s; and the ruins of Syria in the 2010s. And more. The sheer geography he traversed, the quantity of miles and the range of experience, is astounding. Yet throughout, a particular motif—direct and unwavering eye contact—persists, punctuating the show with a relentless and penetrating power.

When I visited the exhibition earlier this year, I was astonished to find that the galleries were absolutely packed, a tightly knit queue of enrapt visitors shuffling along the walls at a slow but steady rate, and growing discernably quieter and more subdued from one gallery to the next. McCullin’s photographs are captivating for both obvious and unnerving reasons, as they depict moments of human conflict, cruelty, suffering, desperation, depravity, and destruction with a wide-eyed and unapologetic directness.

Don McCullin, Northern Ireland, The Bogside, Londonderry, 1971

© the artist

It was heartbreaking to watch visitors move from one horrific scene to the next casually and in time with the surrounding throng. But occasionally, when a subject’s gaze reached out from the frame, this collective procession would come to an abrupt halt. Each one of us was struck not only by the force of what we were looking at—an instant of connection and recognition, often caught moments before death—but also by the unsettling fact that as viewers we were just looking, while the person facing us could look no longer. McCullin’s photographs demand that you stop and take a breath.

“I want people to look at my photographs,” McCullin once stated, trying to explain the complex motivations behind his work in the simplest of terms. “I want to create a voice for the people in those pictures. I want the voice to seduce people into actually hanging on a bit longer when they look at them, so they go away not with an intimidating memory but with a conscious obligation.” Despite such intentions potentially seeming naive or idealistic, especially today, within the hyper-skeptical, oversaturated, and often cynical media landscape, Don McCullin insistently serves as a troubling yet poignant reminder that we are still capable of being conscious and connected, and must therefore recognize our obligations as both spectators and citizens of the world at large. McCullin tells us, as he told himself in the field time and time again, “You have to bear witness. You cannot just look away.”

Don McCullin, Local Boys in Bradford, 1972

© the artist

Don McCullin is on view at Tate Britain, London, through May 6, 2019.