Fashion Photography in the #MeToo Era

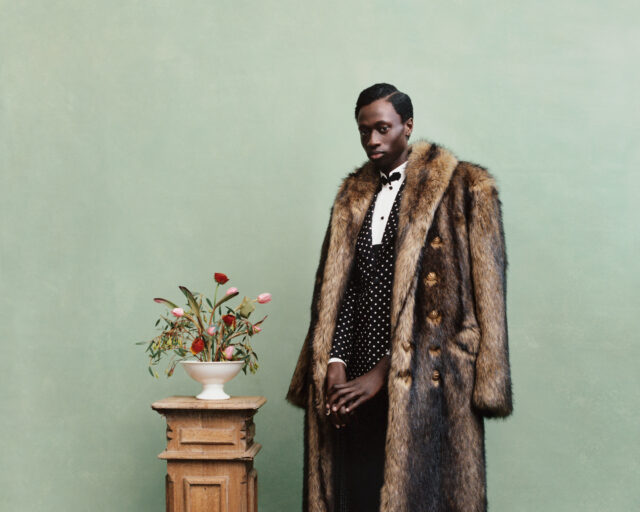

Mert & Marcus, cover of Vogue Italia, September 2017

“I’m not the UN, I’m just a fashion photographer,” says Mert Alas, who, along with his collaborator Marcus Piggott, is known for an uncompromisingly charismatic, glossy style of image-making. He’s commenting on the demand on fashion photographers today to be aware, engaged, political, and, perhaps as a result, increasingly cautious.

In October, it will be a year since allegations against Harvey Weinstein were reported in the press. In this post–#MeToo and Time’s Up era, fashion—which has had its own abusers and brave accusers—is under more scrutiny than ever. That’s good; powerful companies, and powerful men, should be held responsible for their actions. But fashion is in a particularly complex position, partly because fashion itself has never been so fashionable. It’s now a huge part of pop culture, watched by millions and commented on by many. While other industries can express a desire to change through words—expressions of remorse, discussions of new regulations, announcements of new appointments and sanctions—fashion is judged largely on what people see. Images have never been under so much scrutiny, and that scrutiny is shaping the kinds of photographs we see and dictating trends, content, and mood.

Mert & Marcus, cover of Vogue Italia, September 2018

To Alas, despite all the many victories of this modern time we live in, when it comes to imagery, we’re getting more closed-minded. He and Piggott started out in the mid-nineties and fashion was not the industry it is today. Then, shoots lasted days, rather than well-organized hours, and were often conducted by groups of friends for niche titles with a DIY, anticommercial mentality. It would have been impossible to imagine that such images would ever be subject to enormous levels of analysis, or could be digitalized and republished and reblogged by thousands, and taken as a definitive comment on society, politics, women, men, beauty, life. Today, images are simply more seen. And photographers are no longer regarded as image-makers, but increasingly as spokespeople for a set of values. “We used to go for a smaller audience and we had less pressure,” says Alas. “As the audience is so wide now, I feel there is an urge to please everyone. If you stick to your point of view you can always get a good shot.”

Photography, like fashion, is in fashion—it’s everywhere. Some like to say we’re all photographers now, uploading our own personal photo shoots onto Instagram. An average of sixty million images are uploaded to the app each day. Our eyes have never been so accustomed to digesting and dismissing images. Fashion photographer Sølve Sundsbø has seen the resultant spotlight on his industry grow: “I think it’s very important that photography, and fashion photography, are under scrutiny—I don’t think that there is any point being defensive about it. But I think what is interesting is the language and understanding that it’s being scrutinized with. When you go to school you learn how to analyze written texts, you look at books, you read poetry, you analyze written statements, you analyze geography, but the one thing you don’t really get to analyze is images—and if there’s one sense we use more than anything these days, and over the last thirty, forty, fifty years, it’s our sight; we consume images nonstop. But most of us don’t have a way of understanding images; we simply have an old notion that a photograph should tell the truth. And that notion is the underlying premise for most discussions about photography.”

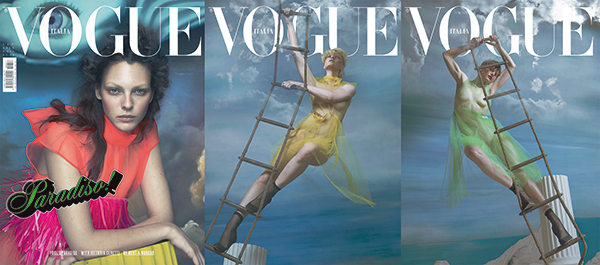

Steven Meisel, cover of Vogue Italia, April 2014

In her germinal book On Photography, Susan Sontag writes, “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened. The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what’s in the picture.” A lot has changed since Sontag wrote that in 1977, but the point she makes is as true as ever. As Sundsbø says, we look to fashion photography in search of some kind of reality. Increasingly, we not only expect that something exists that looks like the picture, but also demand that fashion photography only show things that could exist—hence why we criticize images that do not present a realistic body image, or suitably diverse casting, or a sort of moral sensibility that seems in line with the politics of the moment. Such comments are, of course, important. But they also establish guidelines and tricks for companies to hide behind: make a “diverse” campaign and hopefully no one will look behind it and ask about the demographic of your management board, or the working conditions in your factories. It is a veneer of an ethical industry. “There is a degree of expectation in the current moment that every individual shoot has to be representative in so many ways, and occasionally this feels like pressure to put political or ideological considerations before creative ones,” says Alas. “I personally do cast in a diverse way, but this is because of my artistic point of view. If there is a lack of representation of different kinds, maybe we need to see more points of view rather than token casting choices.”

In an age of “fake news,” it is understandable that people want to be able to trust the imagery they see. But increasingly, imagery that is fantastical or whimsical is seen as out-of-date or off topic. Glamour cannot thrive in this mood. Maybe that’s appropriate, given the uncertainty and difficulty of the times we live in. But it’s also hard to see how imagination can thrive, either. Prioritizing photography as a medium that should be dedicated only to truth-telling also defines the tools of the trade as simply a camera, relegating it to some kind of recorder or note-taker. It ignores the opportunity areas that have come with new technologies like retouch software, apps, and Photoshop. These can be dynamic tools for innovation but are often dismissed as opportunities for trickery, despite the desires of photographers to use them artistically. As Vinoodh Matadin said, when discussing his and Inez van Lamsweerde’s early experiments with digital manipulation in an interview for my book on collaboration, Fashion Together, in 2015: “It was almost like you could finally paint in photography. We never started using digital just to retouch people.”

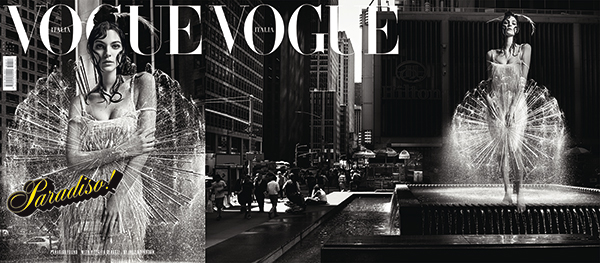

Inze & Vinoodh, cover of Vogue Italia, October 2018

In this climate, there has been a move away from “mise-en-scène” fashion photography, and the representation of dreams or nightmares, to a more documentary-like approach. There is a thirst for something “real” or “raw,” hence the current vogue for imagery that looks natural, clean, quiet, and almost entirely unchoreographed: girls shot by the side of the road, or in quotidian settings, as if they were just stumbled upon. But “real”-looking photography is problematic, too. “The fact that people always believed images should show the truth has always been the strength of fashion photography—it made people believe what they saw in the pictures,” says Sundsbø. In other words, it helps sell bags and dresses, because people really think that they could look just like the girl in the picture. “But now, people are starting to realize the imagery maybe isn’t as true as they first thought, and they almost seem angry about it. One way fashion has reacted is to go toward reality—well, making it look more like reality. But people have to understand that the reality in fashion photography right now is no more real than a fully fledged Helmut Newton Amazon woman in the South of France.” Indeed, you may see an image of a carefree-looking girl, shot in an unexceptional town. But still, that girl is a paid model. Hours will have been spent on getting her to look artfully undone, and art directors and location scouts will have spent days hunting for just the right spot to take the image. Oh, and she’s wearing thousands of dollars’ worth of clothes.

Seven Klein, cover of Vogue Italia, October 2017

Lucy Moore is director of the photography bookshop Claire de Rouen in London, which specializes in fashion and design and regularly supplies to icons of the industry. She’s observed the change in mood in fashion photography. “I have definitely noticed a turn away from an interest in the constructed or abstracted image in the shop’s visitors—instead they focus on archival social documentary and portrait photography as well as self-representation,” she says. “For a very long time, fashion photography needed to generate desire in a very small coterie of wealthy people, who actually had the means to realize their dreams. But with the dramatic turn-of-the-corner into a commercial world where digital space is where the power is won, and where the majority of the users of that space are young, communicative, and not afraid of sparring with their thoughts, maybe aspiration is more about forming alliances—being part of a specific group—than about standing out or entering the rarified world of the elite in a very visible way.”

As Moore observes, most fashion is now consumed in digital spaces: fashion shows are watched on live streams, clothes are bought on e-retailers, and photo shoots and magazine covers are most widely seen on Instagram. Fashion images have thus come to reflect the off-the-cuff, intimate mood on the digital space. That said, it is perhaps ironic that the most criticism of fashion photography—as unrepresentative, or in bad taste, or overedited—occurs on social media, where increasingly users’ own uploads and selfies are as manipulated, tweaked, and tuned as high-budget fashion images. Social media also has its own rules and regulations, which are shaping the future of fashion imagery. It is often described as an area of unbridled freedom and democracy, but really it is rife with censorship. “Image-makers are definitely becoming more daring while, generally, platforms are far from being accepting or willing to facilitate this progress,” say Stefano Colombini and Alberto Albanese, the duo behind Scandebergs, who offer cinematic, narrative-driven images. “Instagram, for instance, is heavily subjected to censorship because of the wider audience it reaches daily.” The most notorious example of this is the ban on showing female nipples, which is surely undermining fashion photography’s long history of breaking down taboos around nudity. “Also,” Colombini and Albanese continue, “with ‘engagement and reach’ being the most important marketing strategy points for brands, images are increasingly being created to be easy to read, rather than complex ones that would reach a smaller audience. It is important to preserve the complexity of every artist’s visual language.”

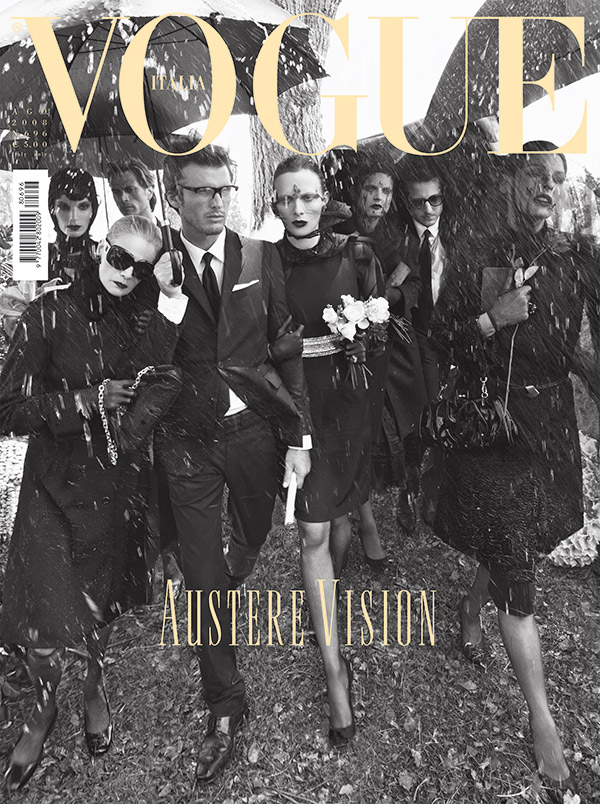

Steven Meisel, cover of Vogue Italia, July 2005

One wonders how some of the more provocative, politically charged images from Vogue Italia’s history, such as Steven Meisel’s shoots exploring society’s obsession with plastic surgery or violence against women, would fare on Instagram in this age of outrage. Social media allows for instant commentary—a quick like or dislike, dictated by a tiny movement of the thumb and a millisecond of thought. “If you do even the smallest mistake, your career might be over,” says Sundsbø. Mert Alas tries to stay brave. “Fashion photography is a tool for escapism, a break from reality, a little dream. I feel like there is a fear of being politically incorrect, and fear creates moderation. Quite frankly I hate moderation—I’m a man of excess!—so I still search for that little dream and try to portray it in our photography.”

So, what is next? Will the taste for the “real” disappear? Will glossy glamour ever feel right? And will fashion ever be able to handle sex? That’s debatable. “I’ve heard men in the fashion industry say they are ‘scared’ of making sexual work. But I hope this doesn’t last. Humans need to be sexual,” says Moore. Sundsbø has had editors shy away from sensual imagery, even in a case where a female portrait subject chose her own dress, which happened to be semitransparent. Somewhere along the way, some people seem to have forgotten that Me Too isn’t saying that sex is bad; it is saying that exploitation is bad. The answer certainly isn’t tasking female image-makers with coming up with a totally new style of imagery. It has become fashionable to talk about a “female gaze,” which is almost becoming an aesthetic in itself, with its own set of limitations and recognizable tropes. “It’s important to not fall into that easy trap,” says photographer Julia Hetta. “What’s important is that we really feel we believe in the picture.”

Steven Meisel, cover of Vogue Italia, August 2008

In the end, the diversity we demand to see within pictures should be reflected in the photographers themselves and the style of images we see: they should be surprising, unexpected, ambitious, and—the most unattainable goal—new. Sundsbø remains optimistic: “Every person hopes that the next thing you do will be the best thing you’ve ever done—whether it’s the next meal that you have, the next purchase you make, or the next person you meet. I have to believe that the next picture I do will at least be better than the picture I did yesterday—you have to have that hope.”

Aperture, in collaboration with UNSEEN Amsterdam’s Living Room Series, will present a panel discussion on the “Elements of Style,” featuring Lou Stoppard, on September 21, 2018.