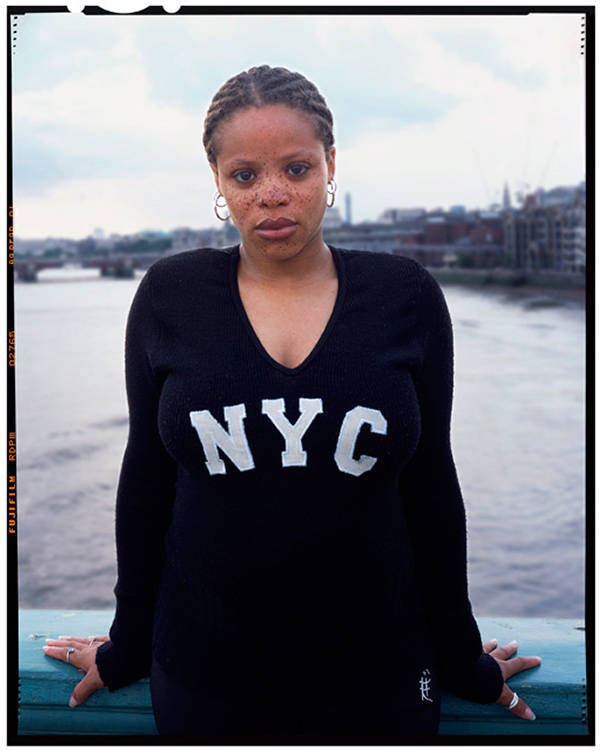

Lola Flash, karisse, 2003, from the series [sur]passing

Lola Flash has spent her career documenting and celebrating the lives of queer people of color through photography. Entering into the field in the 1980s as the HIV/AIDS epidemic began to take hold, Flash became an ardent activist through her image making as she told stories of queer life in New York City during a time of change. A core member of ACT UP, Flash was deeply entrenched in the work of caring for a generation that was reckoning, at the time, with a new disease that transformed the LGBT community; as a result, her art and activism were intimately connected. Today, Flash’s germinal bodies of work—such as SALT, an intimate portrait series of women over the age of seventy, or surmise, which explores gender perception and (mis)representation—continue to serve as an important touchstone for any student of photography, and certainly the lineage of art produced by black, queer women. On the occasion of the opening of her first retrospective at Pen + Brush, I spoke with the critically acclaimed photographer about what it means to reflect on a career of activism and art.

Courtsey the artist and Pen + Brush

Jessica Lynne: Organizing a show of this scale requires you to think about how you’ve evolved as an artist, formally and technically, which must also bring up so many memories. What does it mean to be in this moment of reflection?

Lola Flash: It is very emotional. It’s great to be working with a gallery, although, to be honest with you, I never really wanted gallery representation. My focus as a photographer is really just to say to my beautiful subjects, “Lola Flash thinks you’re beautiful. She’s going to drag her big old camera over and take a portrait of you.” But it’s been great working with the gallery. I really trust Parker Daley and Dawn Delikat at Pen + Brush. As art historians, they saw how my older work, the cross-color work, led to what I’m doing now. In hindsight, I did not really see the connection.

All last year, I was just driving myself crazy. I was thinking, “I’m invisible.” I was making all these posts saying, “Do you see me?” And continuously—it’s nothing new—I’ve been going to galleries and museums forever and feeling invisible. So, thanks to this exhibition, I’m finally getting the recognition that is long overdue.

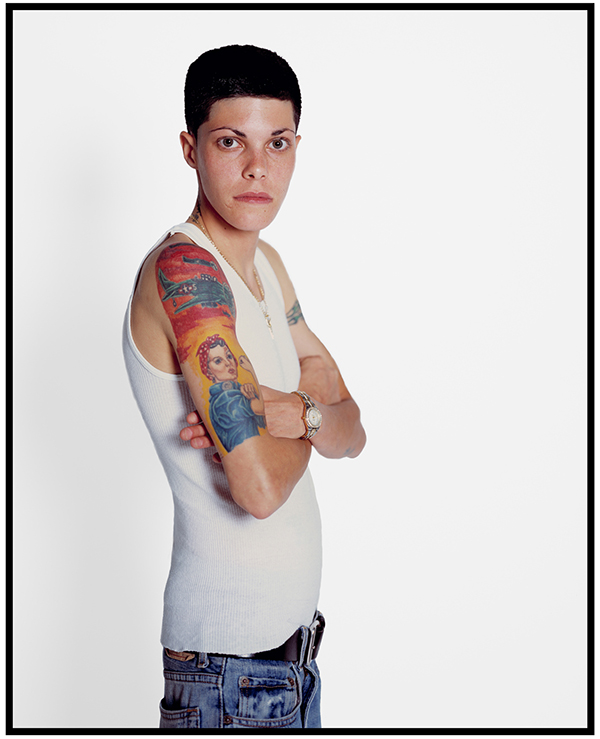

Courtesy the artist and Pen + Brush

Lynne: Why do you think that’s happening now? What feels different for you about this moment versus a year, five, ten years ago?

Flash: So much has changed: the Obama era, the outstanding folks like Deborah Willis, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and even artists such as Carrie Mae Weems and Kerry James Marshall. These people have helped create a different and positive model of the African American experience and I am riding that wave. And, of course, I am terribly thankful to Pen + Brush for seeing me and promoting my work in such a gorgeously professional manner.

Courtsey the artist and Pen + Brush

Lynne: What does it mean to celebrate and think critically about the lives of gay, lesbian, and queer black folks and other queer people of color, and also recognize that sometimes those people may not find their way into these kinds of art institutions—that the infrastructures are often set up to not allow that in the first place?

Flash: Right. That is why I never really wanted gallery representation. For years, when I was younger, I used to show in pubs or restaurants, because I wanted the people who I was photographing to be part of the conversation. One of my friends, Arnie Charnick, he used to do—he still does—a lot of amazing murals in the East Village. He was one of the artists I really started to admire early on, and he never really wanted a big show. He was just really happy with making his murals.

But it wasn’t until I saw the Kerry James Marshall retrospective at the Met Breuer and noticed the way that people were looking at his paintings that I thought to myself, Maybe there is value in exposing my work to audiences that I am not particularly concerned with, thematically speaking. I think it opened up my mind to a subject that I was really kind of against for so long. Of course, I want my work at the Met, of course I want my work at some of these big places. But it’s definitely not the root of why I do what I do.

Courtsey the artist and Pen + Brush

Lynne: Was there a moment when you realized that photography was the tool that you wanted to use as you reckoned with all of these larger, complex concerns about identity?

Flash: When I was a child, the camera was a toy that brought me hours of fun. Once I became a photography major at MICA, I created a process which I coined “cross-color.” This process was before Photoshop, and was a comment on the notion of perfect “Kodak days”—in reverse. I was known for this process; it was my signature style. The colors were so vibrant and all hues were reversed. Blue became red and white became black. I was consumed by the psychological meanings of what colors were supposed to mean. My work continues to focus on issues around race, gender, and sexism, but in a more direct way.

Courtsey the artist and Pen + Brush

Lynne: Now that you are in this moment of reflection, what’s coming next for you, Lola? How do you think about the futurity of your work and practice, your self-sustainability, and legacy?

Flash: Legacy is a very important part of my drive. I think about all the people who stood up for our rights—my ancestors—I feel like I have a commitment to them, and I’ve been given the tools. I have a presentation about legacy that I show the kids I teach in the first days of the school year. I say to them, “If you don’t feel like you have a legacy, then maybe it’s you who’s going to start it.” And so, for me, I want to make sure the work is contextualized properly, alongside the work of my peers, so that people can see the validity of my photography.

Lola Flash: 1986–Present is on view at Pen + Brush, New York, through March 27, 2018.