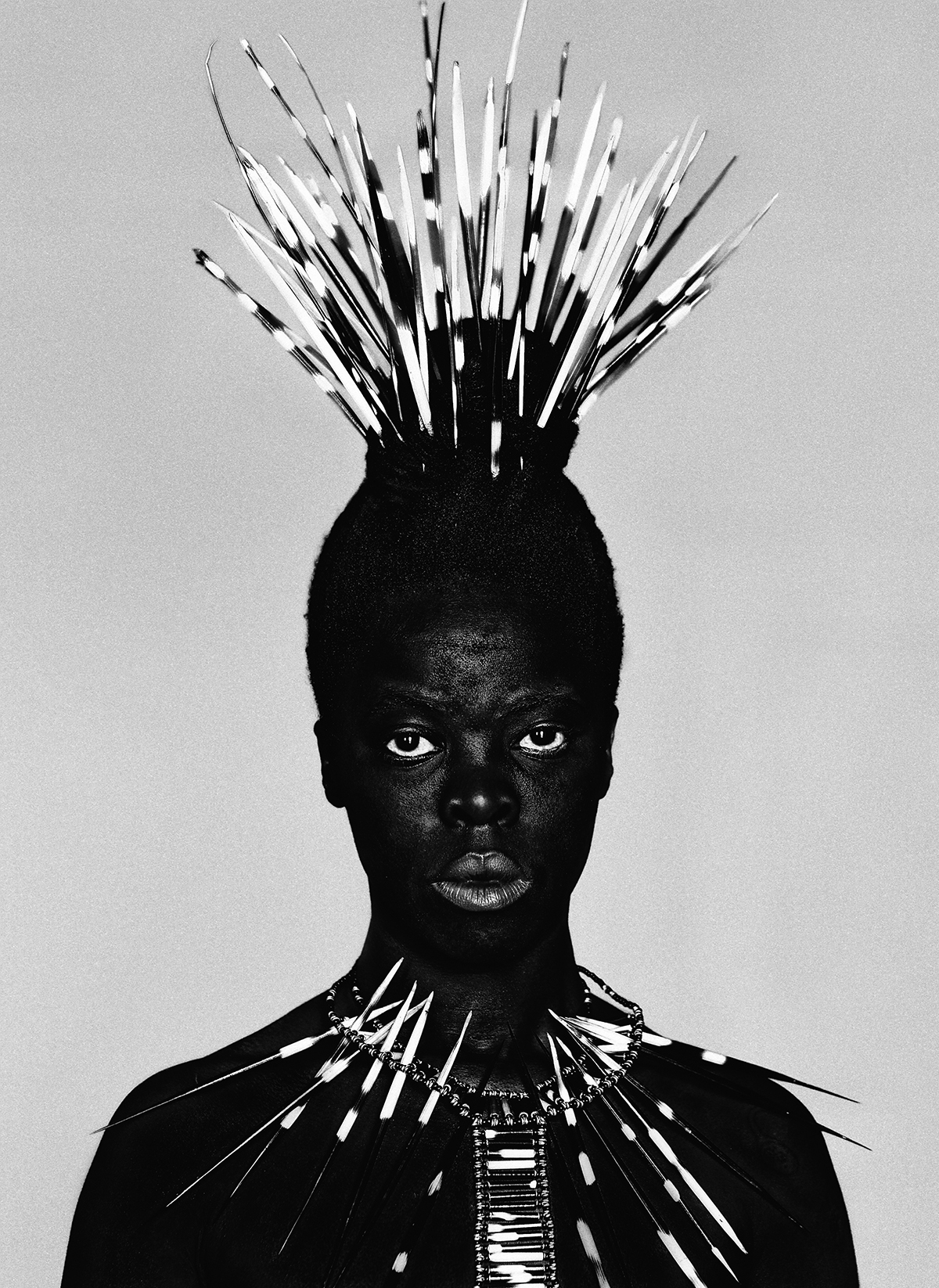

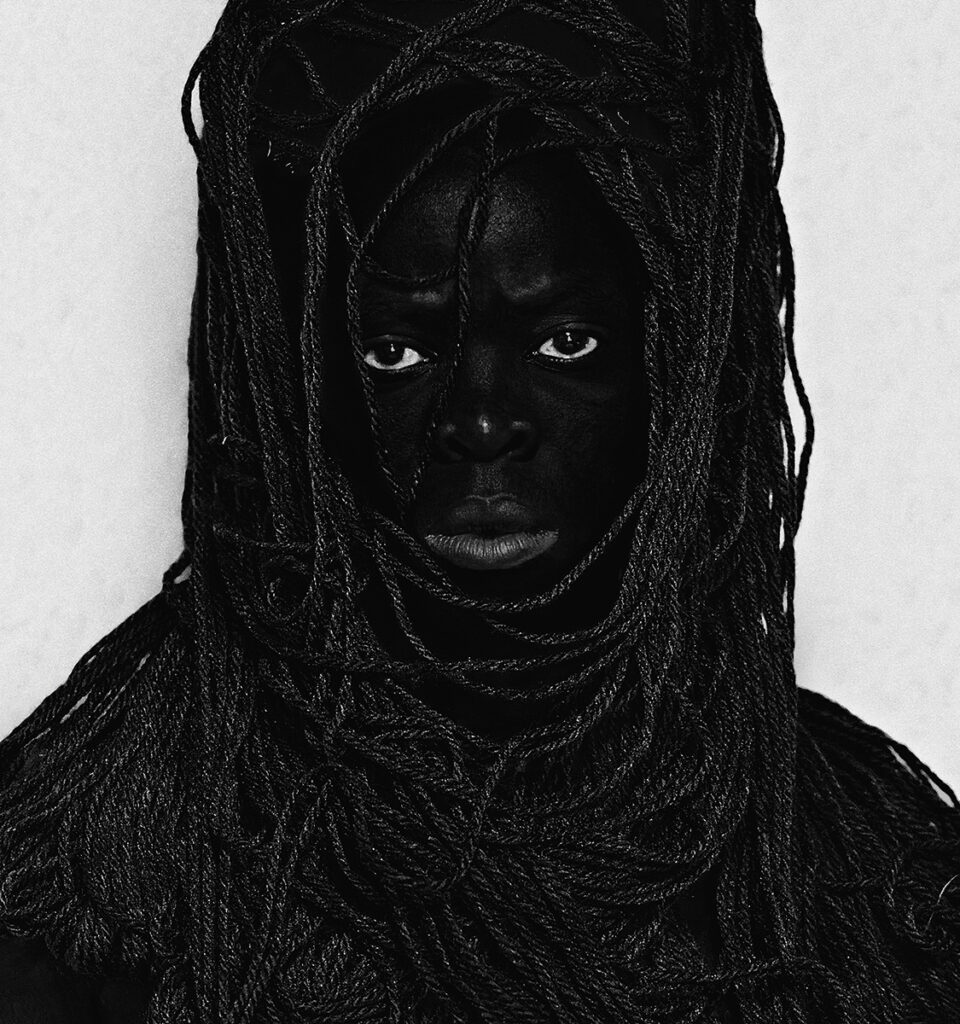

Zanele Muholi, MaID X, Durban, South Africa, 2015

Renée Mussai: Let’s begin by talking about how the images in Somnyama Ngonyama offer a repertoire of resistance, both for yourself and for empowering others. Collectively, they represent an invitation to see yourself in a different light. You take on the image archive in the racial imaginary, addressing a range of personal experiences, social occurrences, cultural phenomena, past histories, and contemporary politics through self-portraiture. Each portrait poses critical questions about social (in)justice, human rights, and contested representations of the black body, confronting the viewer with a stance that is at once personal and political. How does the project sit within your wider bodies of work?

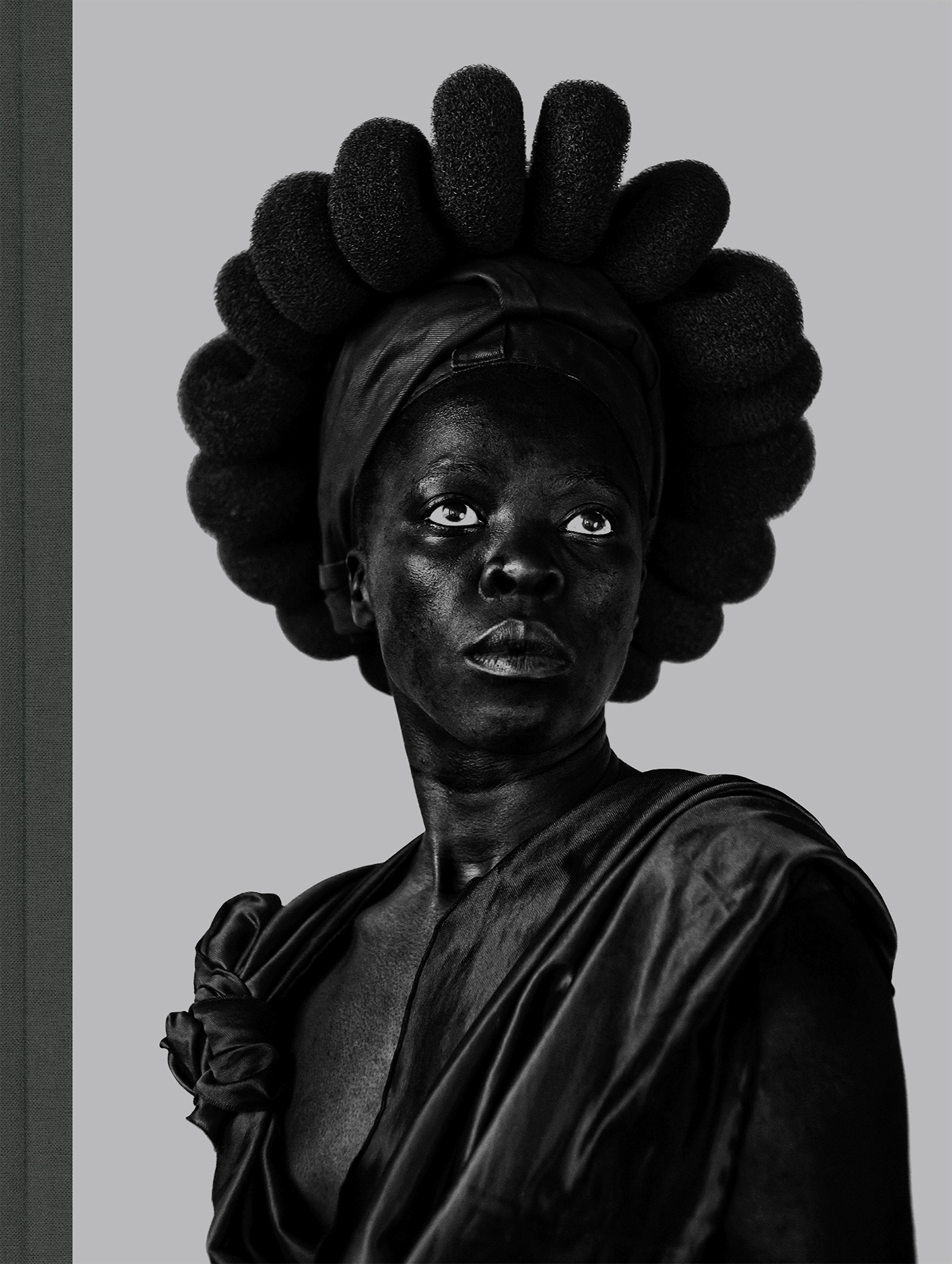

Zanele Muholi: My practice as a visual activist looks at black resistance—existence as well as insistence. Most of the work I have done over the years focuses exclusively on black LGBTQIA and gender-nonconforming individuals making sure we exist in the visual archive. (In Faces and Phases, I focused exclusively on LBTQ individuals, for instance, bearing in mind that gender politics are complex, and fluid; the acronyms are always shifting and changing.) The key question that I take to bed with me is: what is my responsibility as a living being—as a South African citizen reading continually about racism, xenophobia, and hate crimes in the mainstream media? This is what keeps me awake at night. Thus Somnyama is not only about beautiful photographs, as such, but also about bringing forth political statements. The series touches on beauty and relates to historical incidents, giving affirmation to those who doubt whenever they speak to themselves, whenever they look in the mirror, to say, “You are worthy. You count. Nobody has the right to undermine you—because of your being, because of your race, because of your gender expression, because of your sexuality, because of all that you are.”

Mussai: I see at the heart of your project the desire for remedial, permanent inscription into a wider visual narrative, and to affect future histories through visual interventions. We have spoken in the past about how your affirmative portraiture practice evokes W. E. B. Du Bois’s Paris Albums 1900. Challenging the historically racist imaging machine—though with a distinctively heteronormative focus—Du Bois’s strategic assemblage of several hundreds of photographs depicting African Americans in turn-of-the-century Europe similarly represented a site of resistance, enhancing existing visual histories that had tradition-ally rendered certain communities not only invisible, but inferior. I’m thinking of your Faces and Phases (2006–) series in particular, but I feel this equally holds true for Somnyama; the many “faces and phases” you conjure not only bear witness to your own existence, but persist, and insist on, making a claim for humanity. Inviting us into a multi layered conversation, each photograph in the series, each visual inscription, each confrontational narrative depicts a self in profound dialogue with countless others: implicitly gendered, culturally complex, and historically grounded black bodies.

Muholi: Somnyama is my response to a number of ongoing racisms and politics of exclusion. As a series, it also speaks about occupying public spaces to which we, as black communities, were previously denied access—how you have to be mindful all the time in certain spaces because of your positionality, because of what others expect you to be, or because your tradition and culture are continually misrepresented. Too often I find we are being insulted, mimicked, and distorted by the privileged “other.” Too often we find ourselves in spaces where we cannot declare our entire being. We are here; we have our own voices; we have our own lives. We can’t rely on others to represent us adequately, or allow them to deny our existence. Hence I am producing this photographic document to encourage individuals in my community to be brave enough to occupy spaces—brave enough to create without fear of being vilified, brave enough to take on that visual text, those visual narratives. To teach people about our history, to rethink what history is all about, to reclaim it for ourselves—to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back.

Mussai: Yes. Gordon Parks’s notion of the camera as his choice of a “weapon . . . against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs” comes to mind, as well as Audre Lorde’s potent rejection of being “crunched into other people’s fantasies . . . and eaten alive.” And perhaps most relevant, Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s bold declaration to use “Black, African, homo-sexual photography” as a weapon to resist attacks on his integrity and existence on his own terms. I’ve been thinking further about the idea of “weaponizing” one’s practice lately, in relation to Somnyama—not necessarily in a militant fashion, but as a visually seductive call to arms, a protective mantle, a necessary reclamation. An occupation, manifesto, and invitation. These portraits are, essentially, about courage: the courage to emerge; the courage to reflect; the courage to exist, insist, resist; the courage to step in front of the camera—to literally “face oneself.” While you have featured in your work before, you refer to these earlier images as “portraits of the self,” as opposed to the self-portraits in Somnyama. Why did you choose to become an active participant and image-maker at this stage in your career? Why now?

Muholi: I wanted to use my own face so that people will always remember just how important our black faces are when confronted by them—for this black face to be recognized as belonging to a sensible, thinking being in their own right. And as much as I would like a person to see themselves in Somnyama, I needed it to be my own portraiture. I didn’t want to expose another person to this pain. I was also thinking about how acts of violence are intimately connected to our faces. Remember that when a person is violated, it frequently starts with the face: it’s the face that disturbs the perpetrator, which then leads to something else. Hence the face is the focal point in the series: facing myself and facing the viewer, the camera, directly. Coming from South Africa, I doubt that it would have been possible to execute this project as a black person prior to 1994, for instance, because of the apartheid system and laws that were in place.

Mussai: Given both the personal nature and sociopolitical critique that underpins so many images in the series, I imagine that’s especially true. Was there a specific event that inspired the first portrait in Somnyama?

Muholi: In 2012, I was on an artist residency in Italy, where I stayed in a very, very beautiful place: an old castle. But every morning I’d be woken up by gunshots. Even though the space was protected, and we were guaranteed our safety, these continuous gunshots were unnerving for me. When I inquired, I was told they came from hunters, hunting for boars. The catch of the day was described as a “wild, black pig.” At the same time, there was controversy around [the soccer tournament] UEFA Euro 2012: black Italian players were subjected to overt racism, with “monkey” chants and bananas being thrown at them on the pitch. It made me think of how we are perceived as black people—and how black bodies are routinely exposed to danger. Anything black is always positioned as wild, animalistic, uncontrollable.

It’s a painful notion, and I don’t want to go too deep into it, although it does not go away. Only recently, in December 2017, one of the most important photographs in our history—the famous image of Hector Pieterson by South African photojournalist Sam Nzima—was abused by Selborne College in East London, South Africa. The original image shows Hector’s lifeless body being carried by his fellow student Mbuyisa Makhubo on June 16, 1976, when South African police opened fire on marching schoolchildren in the township of Soweto. To illustrate a flyer for a class of 2017 event, Pieterson’s head was removed, and the faces of Makhubo and Antoinette Sithole, Pieterson’s sister, were replaced with dog heads. If an iconic image exposing the violence of the apartheid regime can be turned into a caricature, then what have we learned (or gained) in twenty-three years of democracy, with regards to the ethics of image production—or in terms of empathy and understanding, forty-one years after the Soweto uprising? This is the reason why Somnyama exists.

Mussai: Unfathomable, to think that not even an image this deeply emblematic of the anti-apartheid struggle is protected from parody. It also serves as a testament to the urgency and unabiding relevance of the series in this contemporary moment. I want to return briefly to the inaugural portrait: I vividly recall you telling me about a new project back in 2012, then tentatively titled the Black series before it became Somnyama. When you returned home to South Africa after Italy, you created Sthembile, Cape Town (2012), in response, correct?

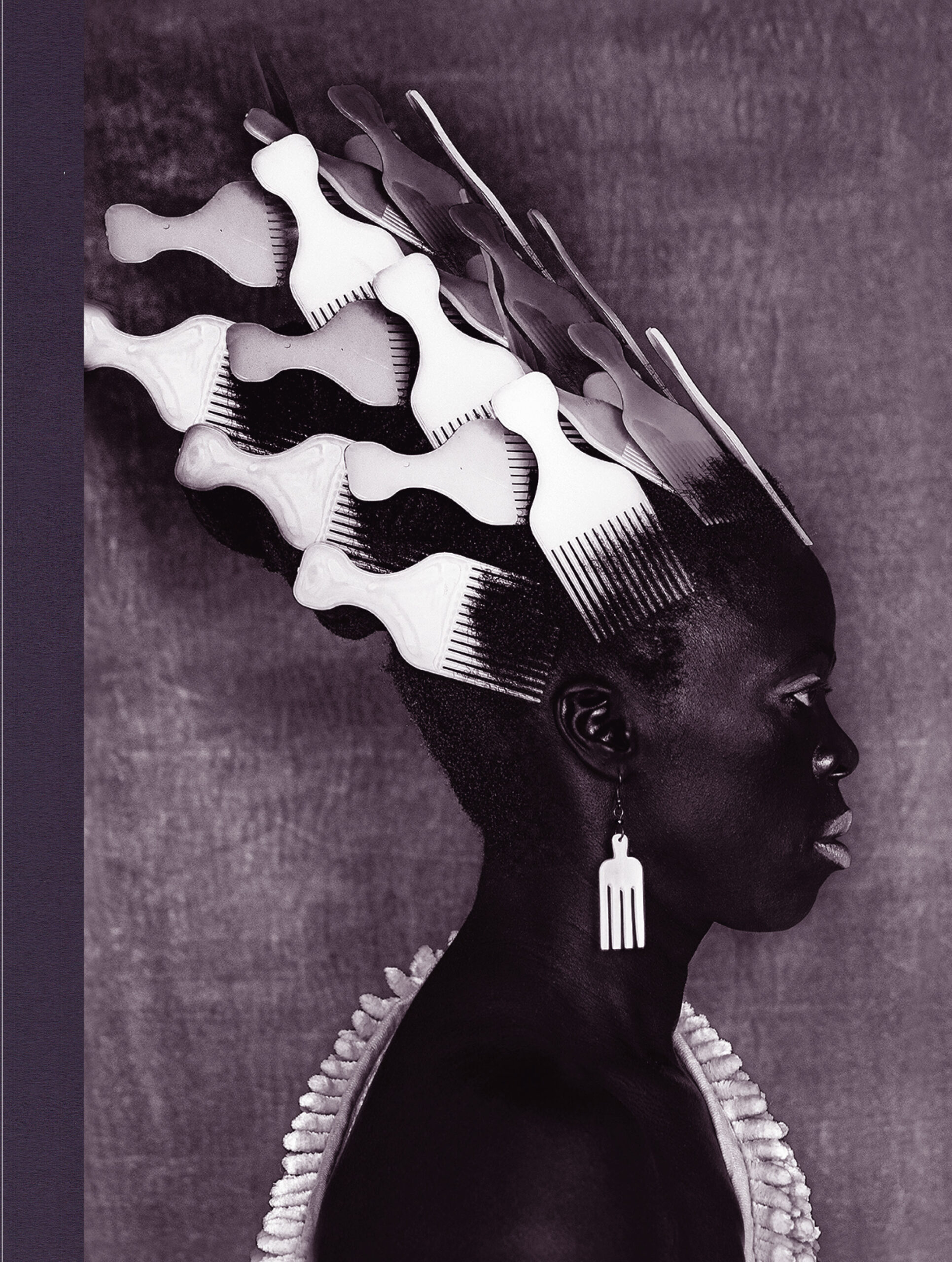

Muholi: Yes. I used materials that spoke to my presumed cultural identity as an African, while referencing a particular historical mode of representation. All of this stereotyping inspires a deep-seated hatred of the black body, from head to toe: facial features, eyes, lips, everything. It could either be wild, as in uncultured, savage, or how your hair is defined as “nappy,” “dirty”—all those things. In August 2016, there was a high-profile case in South Africa at the Pretoria High School for Girls where pupils were reprimanded by one of the teachers because of their Afro hairstyles. As a student, how are you expected to concentrate if your educator tells you that your natural hair is “untidy”? You see this person on a daily basis, in a space where you are supposed to be receiving an education.

Mussai: And, instead, you are effectively told to police your expressions of blackness.

Muholi: Exactly.

Mussai: It’s poignant to me that the inaugural portrait in Somnyama was inspired by an experience in Europe, as this sense of “otherness” becomes so much more . . . pronounced, perhaps, or dangerous, when you find yourself in spaces where your blackness is often experienced as the defining marker of difference. How has being on the road, constantly in transit, and living a nomadic life affected the series over the years?

Muholi: It’s obviously different between here and there. In America, Europe, or Africa, the experience is never the same. But that judgment, that discrimination, that lingering sense that you are not supposed to be here, persists—having to continually justify your presence. Especially at hotels, the ritual of checking into your room can be so traumatizing. Sometimes you’ll be the last person attended to; at other times, you are made to feel as though you are lost, or looking for directions, rather than treated as a paying guest.

Mussai: And these experiences are then translated into Somnyama?

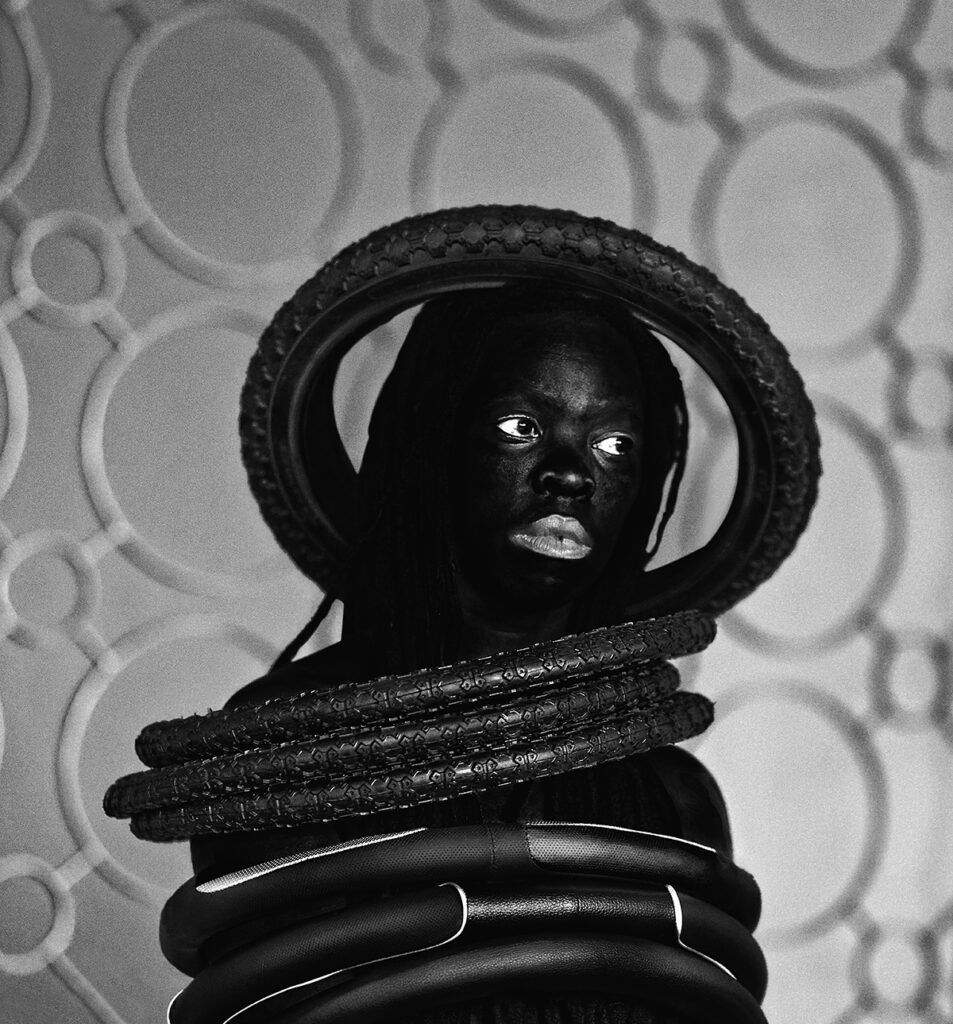

Muholi: Yes. I made a portrait following one of my negative hotel experiences in September 2016 in New York, with strings of wool framing my face, like a scarf. The title of this piece, Dalisu, New York (2016), means “make a plan.” A majority of the photographs in Somnyama Ngonyama are based on my personal experiences. On their own, they might not appear extreme, but they accumulate; all those minor irritating questions add up to something. Sometimes it feels as if you’re inside a web—a web covering your face that you have to constantly peel back in order to breathe. Yet you are still giving yourself access to see—to check if what you are seeing or hearing is real. Dalisu talks about the feeling of being strangled alive. I felt entangled and confined, confused and angry. At the same time, it’s an affirmation to myself and others like me—a call to action. A reminder to ourselves not to allow anyone to undermine us, or to be restrained by exterior forces or others.

All photographs © the artist and courtesy Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

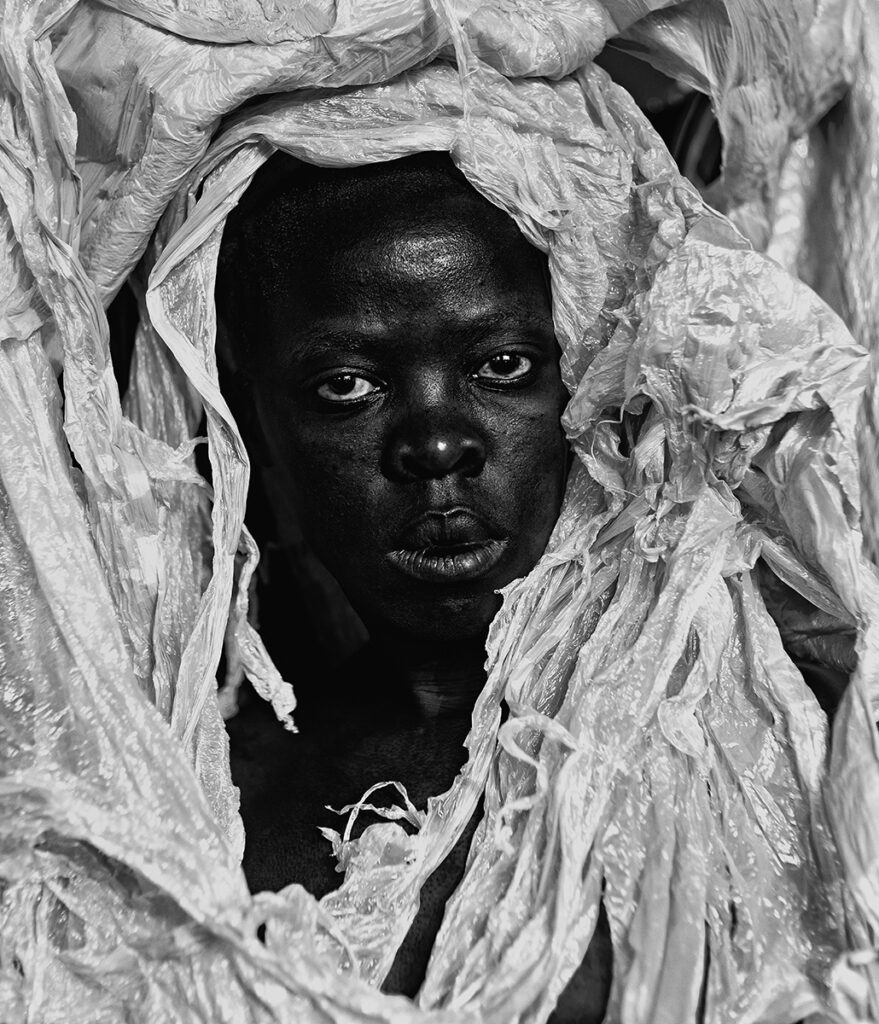

Mussai: Conceptually, this recalls another portrait in the series, Kwanele, Parktown, Johannesburg (2016), where your face is enveloped by layers of plastic wrap.

Muholi: Kwanele responds to the experience of traveling through immigration at different airports where one is often racially profiled. The plastic around my face is the same material that covers my suitcase. So the image speaks about the need for protection, as well as the sense of feeling exposed, stripped of one’s dignity, and continuously scrutinized when passing through border control. In those moments, one often feels like a piece of trash as one moves from one space to the next. It speaks to the painful inconvenience of being delayed by these reoccurring experiences—humiliated, and unnecessarily exposed, as though you have committed a crime. Over and over, security guards will interrogate you: “Where do you come from? What’s the purpose of your visit? How long are you going to be here for? Who invited you?” And so on. You answer all of their questions, and you listen. But you are also very tired because you have been traveling overnight, and you think to yourself, I feel like my bag right now; I feel like trash; I don’t deserve to be asked all these questions.

While you watch another person, who might be of a different race or ethnicity, pass through the border without being troubled, for you, the questions continue: “What are you doing for a living?” “I take photographs . . .” “What type of photographs? Please show me.” But you are not supposed to open your phone at security, acknowledging the sign that says, “No mobile phones.” As you know, I don’t travel for leisure—this is work, always. The portrait is about traveling as a black person, as a photographer.

This interview is adapted from Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness (Aperture, 2018).