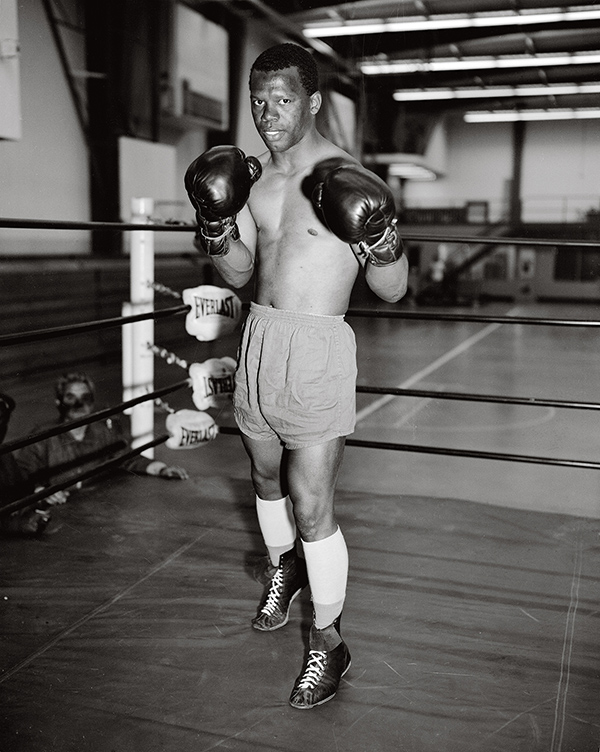

Photographer unknown, WH Woodside, CO Fight, April 8, 1961

Courtesy Nigel Poor, San Quentin Archive, and Haines Gallery, San Francisco

In 1999, at the tail end of a trip to Saint Petersburg, Russia, the artist Nigel Poor found herself standing outside Kresty Prison, the infamous eighteenth-century compound where Leon Trotsky was once held and Anna Akhmatova visited her incarcerated son. Scattered on the ground were dozens of paper cones, weighed down with pieces of bread, small missives tossed out by those behind Kresty’s brick walls. Poor bent down, picked up one of the cones, and took it back home to San Francisco. She has never opened it up. “I wanted to live with the mystery,” she told me one morning as she sat in her car, preparing to make a now frequent commute to California’s San Quentin State Prison.

Photographer unknown, Gym Crew, November 5, 1975

Since the 1990s, Poor’s photographic series of found items, or banned books laundered like clothes, or portraits of the hands of people who visited her studio have navigated the borders between the known and unknown, using objects or visible features as a means of traversing the divide between the two. These days Poor is best known as a cocreator of Ear Hustle, a widely acclaimed podcast released in 2017 that was produced entirely inside San Quentin State Prison and takes its name from prison slang for “eavesdropping.” In each episode, Poor and her cohost, Earlonne Woods, and sound designer, Antwan Williams—both of whom are serving sentences at San Quentin—engage prisoners in funny, frank, and devastating explorations of topics such as solitary confinement and finding cellmates, but also what it means to confront love, intimacy, hope, aging, sickness, and death while incarcerated.

Photographer unknown, Smith Assaulted, February 3, 1965

“We’re not journalists,” Woods and Poor frequently tell listeners, an unsubtle reminder that their stories should not be taken as literal documents of what it means to be an inmate at San Quentin. “Our project is about inside and outside people working together, and how we understand each other and misunderstand each other,” Poor told me. It’s exchanges that interest Poor—the paper cones dropped outside Kresty, her elaborate childhood collections of Popsicle sticks and other things people discarded on the ground, the accidental ways we leave behind impressions of ourselves. In one of the luckiest of those accidents, Poor stumbled on an astonishing visual archive from San Quentin, some ten thousand images depicting prison life at its most murderous and its most mundane. It led to San Quentin Project #3: Archive Typologies (2012–ongoing), a project predating Ear Hustle that continues to occupy Poor today.

Photographer unknown, San Quentin School Special, 1958

The roots of the San Quentin project stem from 2011, when Poor and her colleague Doug Dertinger began coteaching a history of photography class through San Quentin’s Prison University Project. They had to drastically adapt the course they taught at California State University, Sacramento: neither books nor cameras were allowed into the facility. In one exercise, Poor asked her class to create “verbal photographs” instead—describing a memory for which they had no photograph, detailing how they would re-create it, frame it, light it, print it. Her students, she discovered, were keen observers. “If you survive in prison,” she told me, “you have to notice everything around you.” In another exercise of “mapping,” Poor gave each student a 17-by-11-inch photograph, each by a different artist and each printed with a wide margin, where she asked her students to dissect the image and then write a response, formal or creative.

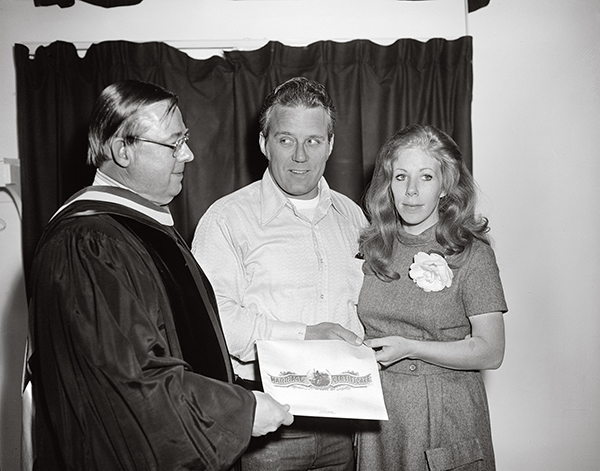

Photographer unknown, Wedding, n.d.

Every image shown in class had to be cleared by administrative officials, who initially deemed anything depicting children, drugs, violence, or emotionally complex issues to be off-limits. “I thought, What’s left?” Poor said. She was ultimately allowed to bring in almost all of the photographs she wanted, with the notable exception of a few by Sally Mann and Nicholas Nixon. Her students cataloged minute details of light and angle: A William Eggleston photograph of a Ford Mercury’s open hood triggered, for one student, the most evocative and meaningful memories of his life. Joel Sternfeld’s McLean, Virginia (December 1978) prompted another story of loss and abandonment, as well as a recipe for pumpkin pie. After the first semester, “one student told me he could now see fascination everywhere in San Quentin,” Poor said. “That was just so beautiful.”

Photographer unknown, Untitled, n.d.

One day, in 2013, Poor noticed a few boxes of photographic paper in the office of Lieutenant Sam Robinson, the public information officer whose voice Ear Hustle listeners hear at the end of each episode (he personally approves each broadcast). “That’s nothing,” Robinson told her. He opened a file storage box; inside were hundreds of 4-by-5-inch negatives, each in a little manila envelope with a date and a cryptic description: “Assaulted in Print Shop,” “Football Game,” “New Exercise Fence.” Poor learned from him that more storage boxes were filling a room. “I’m not exaggerating when I tell you my heart just stopped,” Poor told me. She was granted permission to take home a box to scan. This first batch turned up violent images, including one of an assault victim, but also some of men in a classroom and a man carving a giant ice sculpture.

Photographer unknown, Prison Rock Band, June 26, 1975

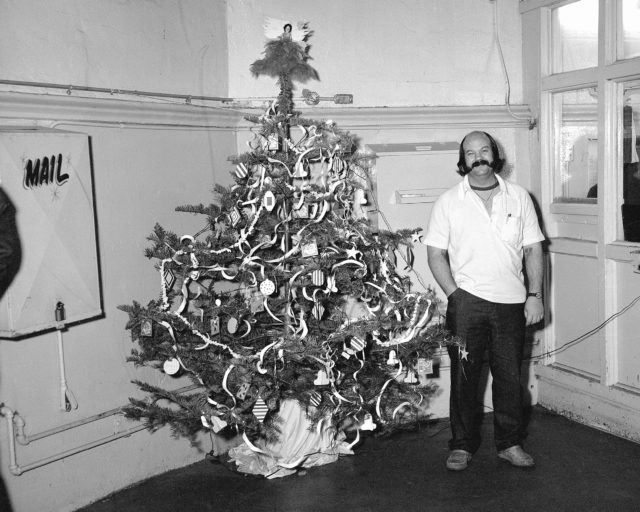

The thousands of images represent the work of corrections officers, who ostensibly made them in a purely documentary sense: to keep a record of incidents and events, weddings and stabbings, Christmas trees, lunchtime, the prison band, the eerie masked dummies some prisoners concocted when they attempted to escape. “It’s everything about life in prison that you see when you go in there,” Poor said, “the most depressing and funny and bizarre.” Poor is assembling an archive of the photographs, for teaching and as part of San Quentin Project #3 organized under twelve categories that reflect the aching divide between inside and outside. Among her typologies: “Holidays & Ceremonies,” “Animals & People,” “Escape & Confinement,” “Murders & Suicides,” “Blood & Evidence,” and, her favorite, “The Ineffable.”

Photographer unknown, Football, October 19, 1974

Poor has discovered no negatives made after 1987. Presumably someone is digitally recording similar scenes in San Quentin now, but it’s curious why a true archive was never attempted, or why, in still predigital times, the photographs stopped. “I’m not interested in them as documents. That’s someone else’s job,” Poor said. “But there are so many details in the photographs I sometimes felt I needed an escort to guide me through them.” With Lieutenant Robinson’s approval, she began asking her students to map onto the San Quentin images too, prompting the kinds of discussions that unfold on Ear Hustle, excavating issues of race and violence and humiliation. “Ultimately, I think showing them these pictures is validating their experiences and giving them a way to talk about their trauma, how unfair life can be. It gives them some tangible truth.”

Photographer unknown, X-mas Tree, December 28, 1975

All images courtesy Nigel Poor, San Quentin Archive, and Haines Gallery, San Francisco

But these anonymous photographers, she tells her students, were framing the world too, making implicit choices about what the camera revealed and, most importantly, what it did not. “It may be in this state of not knowing that we are ultimately given the opportunity to engage in the most difficult of life’s questions,” Poor writes. She calls the San Quentin Project #3 photographs “unreliable witnesses.”’

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 230, “Prison Nation,” under the title “San Quentin Archive.”