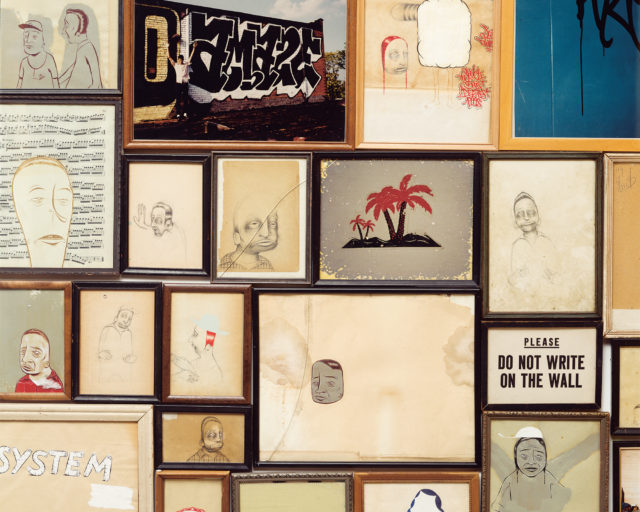

The Surreal Landscapes of California City

From the air, photographer Chang Kim discovers a city that never was.

Chang Kim, Utopia incomplete 160616_05, California City, CA, 2016

Courtesy the artist

In his recent book, The City That Never Was: Reconsidering the Speculative Nature of Contemporary Urbanization (2016), architect and urbanist Christopher Marcinkoski writes about the strange fate of entire cities created for the speculative possibility of future financial gain. For Marcinkoski, these are places of urban development predicated not on real, existing demand in the current marketplace, but on projected possible consumer interest in an unrealized tomorrow. They are cities for people who don’t exist yet, funded by “increasingly complex transactional instruments” whose value is divorced from anything resembling civic good or democratic well-being.

The resulting developments often fail before reaching the point of being even partially inhabited, Marcinkoski warns. At times, they are abandoned long before construction is complete, deserted by their heavily leveraged investors and left in an eerily half-finished state that has no clear resolution. The result is a kind of zombie urbanism, both undead and stillborn at the same time.

Chang Kim, Utopia incomplete 160629_05, California City, CA, 2016

Courtesy the artist

California City is roughly two hours north by northeast from the desert edge of Greater Los Angeles. It was launched in 1958 as the dream of real-estate developer Nat Mendelsohn, who saw it not just as a healthy investment, but as a place that would someday exceed Los Angeles itself in both scale and quality of life.

By land area alone, California City is today the third largest municipal area in the state of California. Yet outside of its small, developed core—complete with a park, fast-food restaurants, liquor stores, and a pharmacy—it is fantastically, surreally, even unsettlingly incomplete. You can drive through California City for twenty minutes or more without even knowing it’s there.

Chang Kim, Utopia incomplete 160603_16, California City, CA, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Seen from an aircraft, however, as in this ongoing series of aerial images taken by photographer Chang Kim (born in Korea in 1974 and now living in Los Angeles), California City’s true scale is revealed. It is, in fact, a bewildering array of gridded streets and culs-de-sac—many named after American automobile companies, such as Buick, Oldsmobile, and Pontiac—scratched into the arid terrain. At times, it seems endless, an immersive geometry textbook of primary shapes all but invisible from the ground, extending forever. The houses meant to appear along these roads and avenues never materialized, of course; the residents meant to live there have yet to arrive.

Sites like California City—or the many failed superdevelopments discussed by Marcinkoski—have, in a sense, become ruins in advance of their own construction. Although radically incomplete, these ghostly locations are not so much remnants of a place or city that once was; they represent the spatial by-products of abandoned financial transactions. They are 3-D receipts for business deals that went nowhere, tragic accounting errors in urban form.

Geoff Manaugh is the author of BLDGBLOG and A Burglar’s Guide to the City (2016).