What It Takes to Be a Photo Editor

The staff of the Capital Gazette, 2019. Photograph by Moises Saman/Magnum Photos for TIME

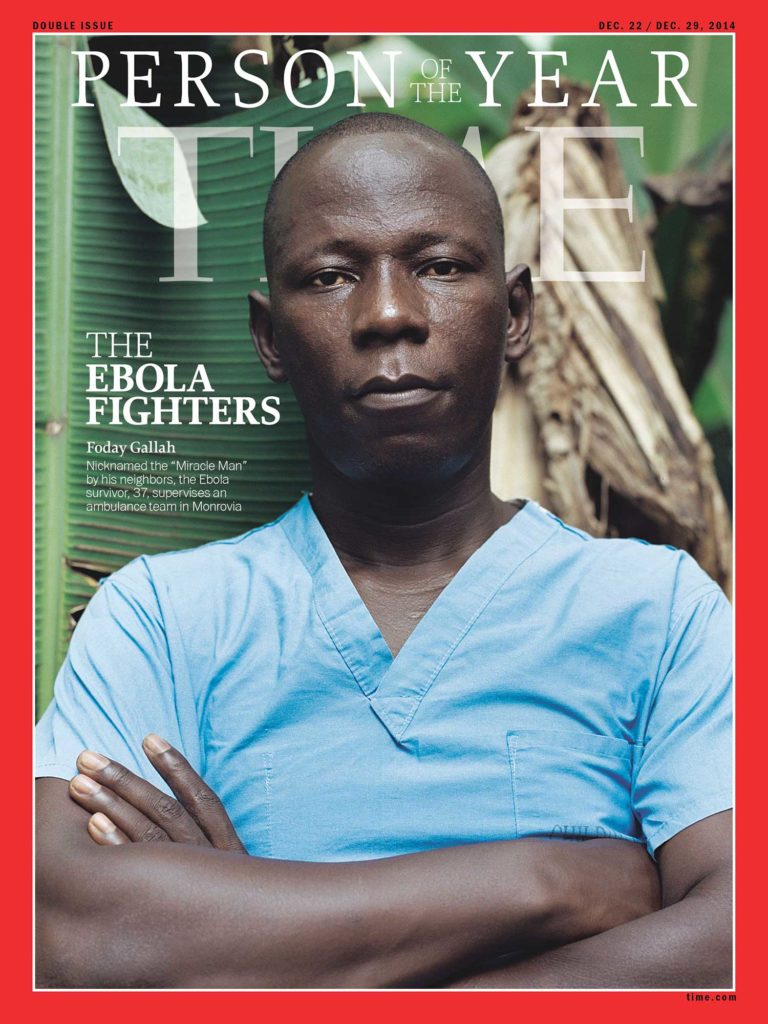

In November 2014, Paul Moakley traveled to Liberia with the photographer Jackie Nickerson to make portraits of the doctors and frontline workers fighting against the Ebola epidemic for TIME magazine’s “Person of the Year” issue. As they waited to see Dr. Jerry Brown, a medical director in Monrovia, Moakley and Nickerson witnessed a burial team preparing to move Ebola victims to a site for mass cremation.

“All I could think about was how no family members were present to witness this final moment,” he wrote in TIME for a behind-the-scenes diary about the photo shoot. “All I could do was hold my head down in respect.”

Covering the Ebola crisis prepared Moakley for the challenges posed by COVID-19, as visitors are restricted from hospitals and funeral homes, and people throughout the world—including reporters—face isolation in all forms. The need to protect photographers and subjects, he says, is as important as telling a story accurately. “Our job as journalists is to point these things out, to show the visual evidence.”

As TIME’s deputy director of photography and later editor at large for special projects, Moakley, one of the cocurators of the 2020 Aperture Summer Open, has produced ambitious visual stories and iconic covers, from a 2018 special issue about the devastating opioid epidemic in the United States, to Ryan Pfluger’s controversial portrait of presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg. He values long-standing creative relationships with photographers, but he also seeks out new voices. “There’s room for everyone,” he says.

When I spoke with Moakley recently, he was calling in from TIME’s temporary photo headquarters—the kitchen at the Alice Austen House, a museum on Staten Island, where he lives and moonlights as the museum’s caretaker. He was working around the clock, figuring out with the team at TIME how to approach the most consequential story in recent memory.

Brendan Embser: How quickly did you and everyone at TIME have to adapt to the new working situation caused by the coronavirus?

Paul Moakley: I went to a shoot in Brooklyn on the March 11—we were shooting the chef José Andrés with photographer Martin Schoeller—and our security person told us we had to follow CDC guidelines and ask everyone who’s entering the room where they’ve traveled. It was really weird being in Brooklyn that day. When I went home on the train, there was one person with a mask on. He had just got it, and he had an Amazon package on his lap. I asked if I could photograph him. I said, “I feel like everyone’s starting to prepare.” He was really excited about his mask. It was camo and kind of cool looking.

Embser: Do you carry a camera with you all the time? Or do you just take lots of pictures on your phone?

Moakley: I do carry a camera around, a little Sony RX100 VII. It fits in my pocket, has a great flash, and takes awesome pictures.

Embser: Some of the best photo editors are also photographers, because they know what’s good and they can cut through things quickly.

Moakley: Yes, sometimes. Jason Fulford, for instance, is a wonderful editor and collaborator. And I think back to the history of photography, to Alfred Stieglitz’s journal Camera Work (1903–17) and the way photographers used to publish magazines and have galleries and also take pictures. I’ve made people like that the model for myself. I’ve often felt some anxiety about needing to specialize in one thing—to be either a photographer or a photo editor.

Embser: And now you have it all!

Moakley: I don’t know if I have it all, I don’t think so! Being a photographer keeps me sharper as an editor. If I’m taking my own pictures and editing them, I feel like I’m better at editing other people’s pictures. It’s like exercise for me. I live in the Alice Austen House, a museum on Staten Island, which is a whole other way of thinking of pictures, as compared to laying them out in a magazine, which is so much more about delivering information.

Embser: We are living in a moment when people are obsessed with information, looking at their news feeds every hour, and possibly even have an unhealthy relationship to the news. On the other side of that are people like you—essential workers, I would say!—who are helping us interpret and understand what’s going on. What has changed for you over the last few weeks? What has it been like to put together visuals and images for a major magazine that is so much a part of the American news DNA?

Moakley: It really hit me in a weird way the first time we had a phone call about what might happen with the virus. We have a security specialist at TIME who worked for the FBI, and she keeps an eye on all of our photo shoots that might have a dangerous aspect to them. All of a sudden, every shoot became dangerous, and this possibility of being locked down as a city came up. It scared me. It took me some time to process how to approach it visually.

Embser: When you realized what was happening, at least in the U.S., how did you develop a cover for the magazine?

Moakley: As things got stranger and stranger by the day, I called the photographer Angela Strassheim. She’s a really wonderful artist. I knew she knew how to make work about forensics. I told her the story is getting really big, and it’s dangerous, and I think we’re afraid to have photo shoots and to bring people together right now. I thought she could do something with fingerprints on everyday objects, all the things you carry around, to raise consciousness about what people touch. We kept talking, a little bit through email and text.

Eventually, Angela called me and said she had a friend in Connecticut who thinks she has COVID-19. “She can’t leave the house, and she’s a single mother,” Angela said. “I was dropping groceries off for her, and I saw her inside her house in her robe with a mask.” And then she said, “That’s the picture I want to make for you.” (Angela makes incredible pictures of people in domestic spaces, and they have this really strange tension that she taps into, like Doug DuBois—they just pick up on another part of the ether that we’re not seeing.)

I had to call the security people at work to evaluate the situation and explain that Angela would never go into the house or have any direct contact with the subject. (We weren’t even thinking six feet yet.) We told her, “Don’t go in the house, photograph through the window, stay far away.” That shoot went really well—Angela made a startling picture of this person trapped in her home with a mask on. This was early on, when we had government leaders telling us we didn’t need to wear masks. But this woman was being really responsible, worried about other people and her son, quarantining in her bedroom, and depending on family and friends to bring her food. So it was a great story.

We then decided to crash a bunch of covers around the world of people who either have COVID-19 and are stuck at home, or have some kind of role as essential workers, like delivery people. It was difficult in China, where they make everyone stay in quarantine. But in the UK, Iran, the United States, Brazil, and all of the other places where our photo department did shoots, we approached them the way Angela did. We had everyone shoot from a safe vantage point, a doorway or window, and it created a series that was very effective. One cover our deputy photo director, Andrew Katz, produced was by David Ryder, a Reuters photographer who works on the wires primarily in Seattle. He was photographing the nursing home in Kirkland, Washington, where there was one of the biggest outbreaks of COVID-19. David made a powerful photo of a middle-aged woman staring into the window of a nursing home and trying to talk to her mother, who was in bed inside. It was like Angela’s picture—this idea of being separated by glass and walls and space.

Embser: Angela’s image strikes me as iconic. It’s a classic TIME magazine cover, quintessential TIME. And the others radiate outward into different styles.

Moakley: That’s the fun thing about working at TIME. You’re communicating to this mass audience and you’re trying to come up with a really smart way to tell a story, like any other magazine—like the New Yorker, New York Times Magazine, or California Sunday Magazine. I love the clarity of Angela’s photograph, along with the message the other covers send that this was not only happening in the U.S.

Embser: What kinds of conversations are you having with photographers about how they’re doing their reporting? Would it be fair to say that everyone is a war photographer now?

Moakley: Yeah, that is exactly what’s happening. Almost every assignment is treated almost like a war assignment. We run through a checklist with photographers, and we make sure we have emergency contacts for them in case something happens while they’re traveling. We have to prepare special letters and IDs for them, so people know they’re essential workers. We have to check and see if they have health insurance, and if they don’t, we can look into getting them some kind of temporary insurance. Then there’s the issue after the photo shoot of what happens to the person, and when does our responsibility to take care of photographers end?

Embser: Have you had an experience like this before?

Moakley: In 2014, I traveled to Liberia with the photographer Jackie Nickerson and writer Aryn Baker to produce our “Person of the Year” shoot. That was a series of photographs around the Ebola fighters, and we were looking at people on the ground in Liberia, specifically Liberian doctors figuring out how to cure people. The Liberian doctor Jerry Brown was the first person to figure out how to get people to recover and walk out of the hospital. It was one of those issues we were so proud to work on, because we were honoring people doing incredible, dangerous work.

Embser: Is it typical that the photo editor would travel with the photographer like that, especially for such a dangerous assignment? Or was that specific to your role producing “Person of the Year”?

Moakley: I would say I’m definitely a rare hybrid of being a producer and photo editor—I produce photography and video, and I also work a lot as a reporter. So I’m useful in these kinds of situations, to multitask. I was also worried about Jackie. We wanted a photographer I had a relationship with, someone who could work without lights and make elevated, beautiful, monumental portraits. Jackie had no hesitation—she understood the dangers immediately, but she was willing to take the risk and felt it was a story she wanted to tell. I wanted to be there as a photo assistant, as a producer, to be an extra set of hands for her, in situations where she needed someone to hold a reflector, hold an umbrella over someone’s head, and to do all the fact-checking for captions.

Embser: I remember the pictures from that period, in Liberia and elsewhere in West Africa, were incredibly distressing—in some cases, they were apocalyptic. Jackie’s covers are regal. They’re not sensational. And I think that’s why, at least in my opinion, they hold up really well.

Moakley: Thank you, that was precisely our intention.

Embser: What was it like for the two of you working together on the ground?

Moakley: It was a moment that really prepared me for COVID-19, I have to say. There was a period during the Ebola crisis when we said, “We are not sending photographers into this, it’s too dangerous.” It was a wall of “No.” But our job as journalists is to point these things out, to show the visual evidence—at TIME, the photo editors all feel strongly about that.

For the shoot, we had the most elaborate security plan—I have it in a binder to this day—and directions to airlift us if one of us got Ebola and we had to be taken out of the country. We were some of the only foreign journalists in the country at the time, and it was spooky to be alone almost, and not see any other press around. I remember learning about PPE [personal protective equipment] and how to apply it properly and how to put it on someone else—it’s really a two-person job to don full PPE.

I went to Liberia with trunks of equipment, and when I got off the plane, a man in a white space suit checked my temperature. Our fixer picked us up at the airport with Aryn Baker, our reporter. I remember he opened the car door, and he had a sweat rag sitting on the seat he wanted me to sit on. I was too polite to say, “Can you move the towel that you’ve been sweating on?” I was just like, Okay, this is where I’m in it. I can’t touch my face anymore. I moved the towel and locked my hands onto my knees until I was in a space where I could wash my hands again.

Embser: When you were working with Jackie and Aryn, did you have a sense that this was a moment you would share for the rest of your lives?

Moakley: Yeah, we all really bonded. There were moments when it really started to escalate—watching Dr. Brown and his hospital, I had a moment as a journalist where I was seeing something that I’d only seen in pictures of genocide: a dump truck loaded up with bodies. Seeing people working so carefully and diligently at a time when they couldn’t really have funerals, they were just trying to take care of the dead, and the dead were sadly being buried without funerals and without family members around. It was one of the most unforgettable scenes I’ve ever witnessed as a journalist, and it marks me to this day.

I remember looking at Jackie, in our gear, and making eye contact with her. We were working quietly, and I thought, This is where you just have to focus and get this. After almost two weeks in Monrovia, the best day was when we were with Dr. Brown and he told us they were sending a whole family home who had recovered. To see this family come out of quarantine, it looked like they were in a camp (like in Holocaust pictures), the gates opening, this family walking out, and they were weakened but smiling and so excited and happy. That really lifted our spirits after seeing such death and destruction. Knowing that people were getting better and that we were on a mission to celebrate the people who were helping them.

Embser: Over the course of your photo editing career, I imagine there have been photographers you have called on repeatedly. What makes those creative relationships work?

Moakley: It’s truly the energy of the collaboration. If I tell a photographer I love some part of their portfolio, I really mean it. I don’t say those things lightly. When you hire someone and they do a job for you, you trust them. On the inverse, you have to publish their work well, treat it with the utmost respect, be their representative at the magazine, and they begin to trust you too. I would say how that relationship grows is the most essential thing about photo editing, because from that point of trust, I can ask them to go a little bit out of their comfort zone. If it doesn’t go well, they know I’ll be respectful, and that I’ll only show their best work.

Embser: How do you engage with photographers you’re commissioning for the first time?

Moakley: When you work with a photographer who has a lot of raw talent, or someone who’s in a place where they are given an opportunity to rise up to the challenge, you have to set up circumstances for them to be successful. And that is really where a photo editor comes in. I think people don’t realize how much production, research, mood board–making, and therapy go into photo shoots. Everyone needs different levels of help. Whether they’re experienced or not, I just want it to be exciting for them. I value the energy of what somebody puts into an assignment, how friendly they are in the back and forth, and their openness to ideas. We spend a lot of time thinking of what the outcome of a shoot’s going to be, because that’s our job, but we also want to be open to the unexpected, and that’s where amazing work happens.

Embser: You are one of the curators of the 2020 Aperture Summer Open, which this year is called Information, inspired by the 1970 exhibition of the same name at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At a time when we have divided ideas about authority and truth, what does “information” mean to you?

Moakley: As a photo editor and journalist working in the new social-media landscape—where you’re called into question more and more, where the audience can respond directly—we’ve all had to work harder. We’re three years into a presidency where this idea of “fake news” has escalated. There’s a whole segment of our country, and the world, that doesn’t believe journalists. I think it’s good to be skeptical—we all need to be—and we need to take a lot of different sources of information into account to come up with our own ideas. But it’s also hurtful and deeply harmful to have such powerful people dismiss organizations that are doing good work. We’re fighting against that every day.

I think we have to let people know what we do, bring them into the process a bit, and be really clear about what’s real and what’s not, especially when it comes to photography. At TIME, we have a mass audience, so we have to account for different levels of visual literacy—letting people know when images are manipulated in some way or when we’re calling it an illustration, and what’s the information that runs next to a picture that might be staged. That is all really tricky and delicate. I think when people come to TIME magazine, there’s an expectation that they’re going to look at news pictures that aren’t retouched or altered in any way. This week, we needed to protect the identity of somebody in a hospital, blurring out the name of somebody in a room, and with that picture, we have to run a statement saying that it has been altered, so the viewer knows that this is a very special picture, that we wouldn’t do this to any other picture. That also sends the message that everything else is real.

Embser: Yet, don’t you think that artists—photographers who are not only working in journalism but also making lens-based artwork—need space to blur the lines between fact and fiction a little bit?

Moakley: Yes, on the other side of things, when we’re talking about art—definitely. My interest in photography has always been in that ambiguous part of it, that power to really play. I love documentary work, but I love documentary artists who challenge the idea of photography’s authority. Some of the most exciting things I’m seeing right now are photographers playing with ideas of sequence and repetition in their work. One of the last bodies of work that stuck in my head was Sohrab Hura’s The Coast (2019). He makes these very intense pictures, but there is something about the repetition, and this idea of seeing a repetition and a sequence, that makes the pictures even more powerful.

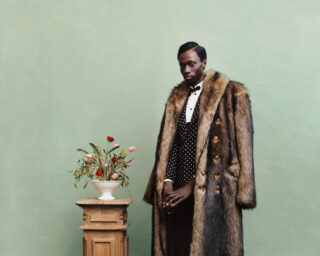

Embser: I have to ask you about the Pete Buttigieg cover. The cover of a magazine, especially the cover of TIME, still holds an amazing symbolic value, even if you don’t buy the magazine or ever see it in print. The TIME cover is like a way station toward immortality. And the concept of the cover has completely survived the leap into the world of Instagram—just look at Tyler Mitchell’s 2018 Beyoncé cover for Vogue. Mayor Pete’s cover is part of a queer trajectory in TIME, from Ellen’s cover from 1997 to Laverne Cox’s cover in 2014. You commissioned Ryan Pfluger for the portrait of Buttigieg and his husband, Chasten, and Ryan is someone who is known for his beautiful and sensitive work around LGBT themes. Can you talk a little bit about how that image was made?

Moakley: Definitely. Ryan Pfluger has been a contributor to TIME for about ten years. As our relationship has grown, I think of Ryan for a number of things. I think of him definitely for queer subject matter (I love the way he photographs men), and he’s obsessed with cinema, so I think of him for movies. I also like his artwork, what he posts on his personal Instagram feed. For this cover, I had twenty-four hours to set it up, and I knew the shoot was going to be ten minutes and that Ryan could work under pressure. I actually felt a little self-conscious, because I was like, Is he going to think I’m calling him just because it’s a queer subject? But Ryan was excited about it.

Last spring, when I flew to South Bend, Indiana, for the shoot, Ryan was waiting at the hotel, ready to have a conversation and to start work right away. This is one of those situations where you have to trust each other. I was really pushing Ryan toward this clean picture of Pete, and we spent a lot of time lighting and setting it up. Pete was on the cover of New York magazine the previous week, so we knew we would have to do something different.

Embser: And you ended up with this totally American portrait, with the front porch and the natural light.

Moakley: Yeah, it was all very fast. I remember Pete opened the door for us, and he was the most normal person in the world. He offered us coffee. (He was walking around with a JFK mug, which made me crack up—I asked him if he would pose in the picture with the JFK mug, and he was totally into it.) Anyway, we made these beautiful painterly portraits of Pete, and then I wanted a secondary shot with Chasten—I didn’t know if Pete and Chasten were going to go on the cover together, but I knew one picture would end up on the cover and one would end up on the inside. We were trying to get as much as possible out of ten minutes. Ryan said he was going outside for a look. I give it to Ryan because he had the instincts to see the house, to see American Gothic. The picture is this queer American Gothic.

Embser: Greta LaFleur in the Los Angeles Review of Books said that this cover offers “the promise that our first gay family might actually be a straight one,” meaning it’s a very straight image of a gay couple, who are adopting the posture of a “regular” American family.

Moakley: They were just being themselves. And that’s a big part of that picture, whatever perception the Los Angeles Review of Books has about them, it’s just Pete and Chasten being themselves. That’s the picture they would have taken for their engagement, they would have stood that way—but then it’s filtered through Ryan, and it’s filtered through TIME, and packaged by TIME.

Embser: And seen around the world. So, perhaps the suspicion derives from the spectacle of someone who is getting all this attention on the American stage, and who happens to be gay, and therefore his perfect nuclear family image is inaccurately associated with a queer community that’s, in fact, completely fragmented and diverse—a population that has many different ideas of what a family can be.

Moakley: Yes, I think so. In my own search for my identity as a queer individual, as a gay man in America, in this generation that comes post–AIDS crisis, I think about how our self-perceptions have changed and what acceptance means. I think it means something different for people in different parts of the country. Pete Buttigieg, like all of us, is growing into his queerness and discovering his sense of masculinity or whatever that means to him.

Embser: The best portraits, and especially those on a magazine cover, have more than one meaning. Ryan’s portrait of Pete is destined to cause disagreement: it’s a touchstone, or it’s offensive, or it’s conformist. It’s “queer” in every sense. It’s also the last of its kind. The next time we have a gay candidate, you won’t need to do a cover like this, because it won’t be a TIME magazine cover story. It’ll just be like, yeah, that’s another presidential candidate.

Moakley: Exactly. If we can make important pictures that people share and talk about—what else could we do that would be better right now? That’s what we hope to do as journalists, writers, and artists. We’re living through extraordinary times since Black Lives Matter and Me Too, and I feel like the internet and social media propelled a revolution around all of our lives and the way we’re rethinking who tells stories. As photographers and the publishing community, we all are in a place where we’re trying to emphasize diversity of perspectives in storytelling. And this goes back to your question about photography: it’s really the artists that lead this. Artists drive all the ideas. And the great art photographers, their ideas trickle down into other things. We all need that inspiration and that energy.