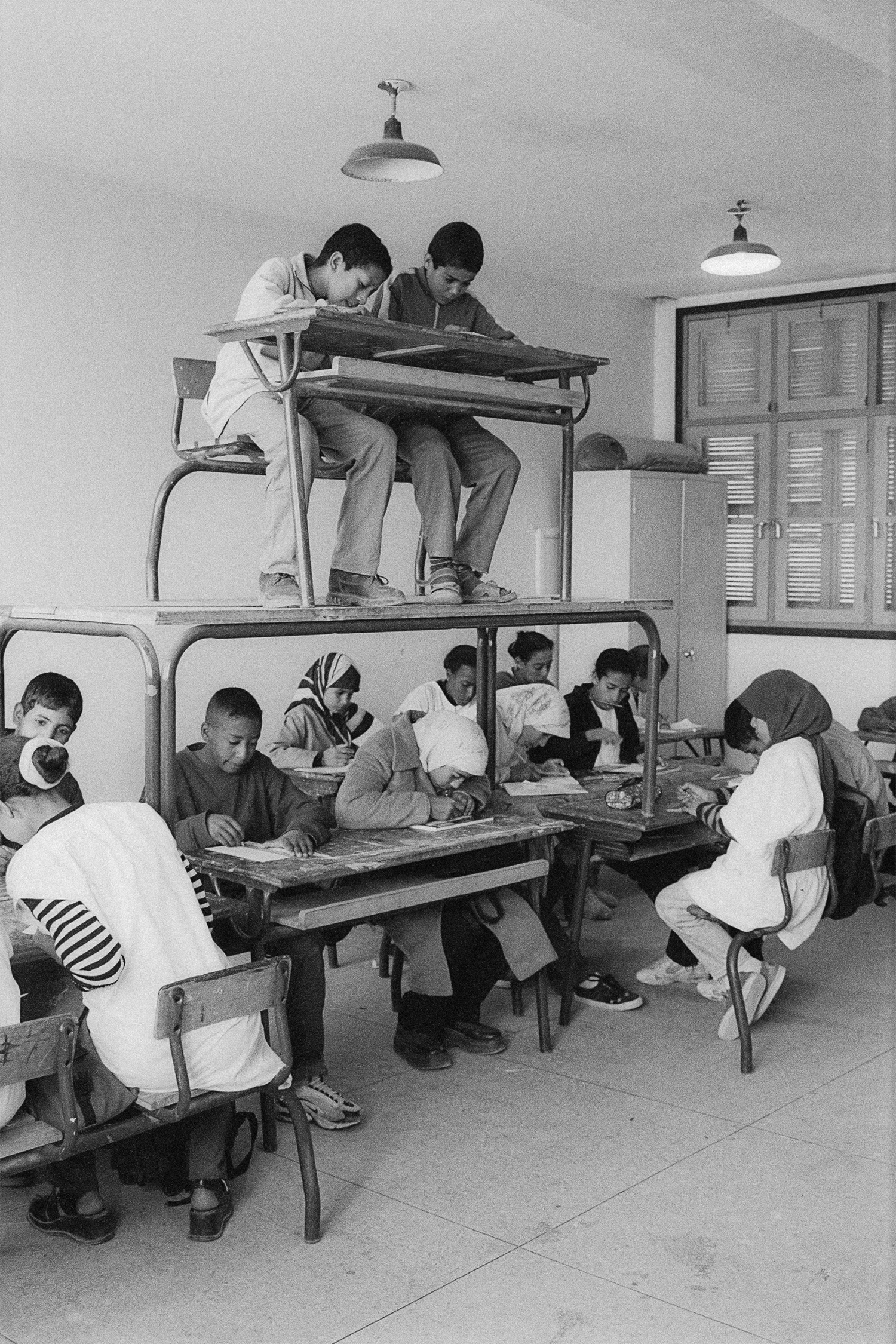

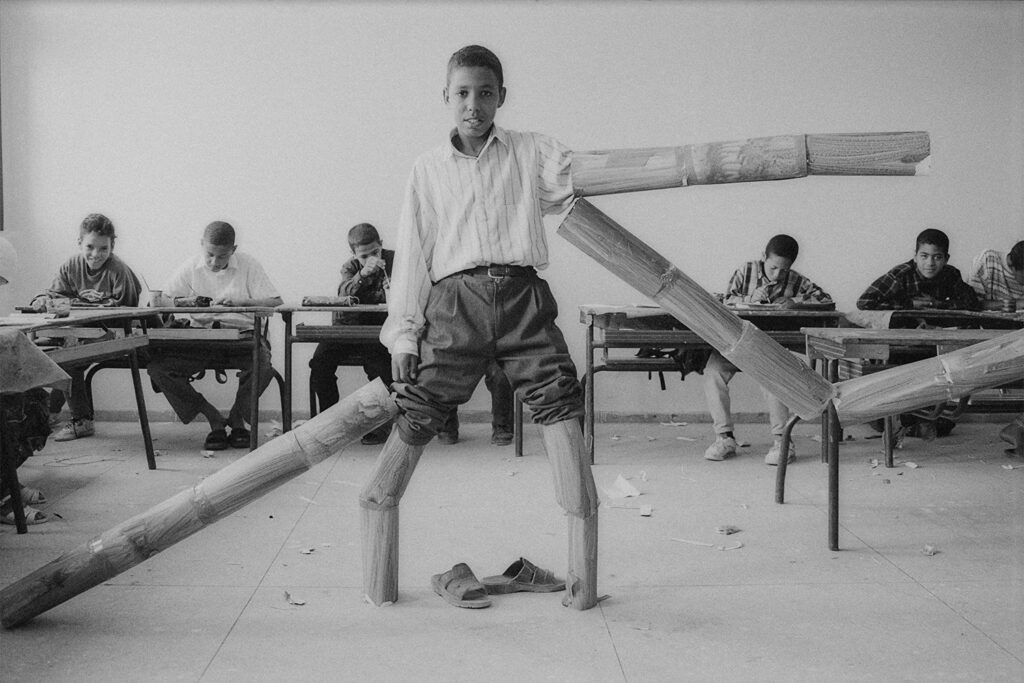

Hicham Benohoud, La salle de classe, 1994–2002

Museums aren’t usually compared to playgrounds. Such institutions tend to rest on their projection of authority and expertise. In the 1980s, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam sought to challenge this assumption through a series of group exhibitions devoted to exploring what play might mean in a typically buttoned-up context. One show titled Moves: Playing Chess and Cards with the Museum, curated by the philosopher Hubert Damisch, sought to transform the exhibition space into a chessboard, where visitors could essentially play a game with the collection. This experiment is cited as inspiration by curator Francesco Zanot in an essay accompanying GAME, the sixth edition of the Foto/Industria Biennale, organized by MAST Foundation in Bologna. Founded in 2013, MAST holds a collection of photographs related to the history of industry and features programming on technology, art, and innovation. The organization also runs a grant program for artists. GAME: The Game Industry in Photography, which was on view this fall, comprised twelve exhibitions at eleven venues.

© the artist and courtesy Sprüth Magers

© the artist and courtesy Galerie Francesca Pia

MAST occupies a sleek glass-and-steel building. An arching reflective sculpture by Anish Kapoor sits outside the ramped entryway, reflecting passersby and the sky. On view was a large exhibition by Andreas Gursky, who for decades has examined the systems and aesthetics of global capitalism. His large-scale, often digitally composited images, feature well-stocked industrial ports, the chaos of a stock exchange floor, jewel-box luxury retail spaces, an Amazon shipping center teeming with a dizzyingly eclectic selection of products, organized by algorithmic preferences. Gursky has wowed audiences by nodding to large-scale history painting to reveal a spectacular world shaped by globalized production and trade. There isn’t much obvious play in these images, aside from that involved in the artist’s own process—where reality is amplified through digital intervention—but the show set the stage as a macroview of consumption, profit, and consumerism. After all, gaming today is a multibillion-dollar industry and gameification of customer experience has become another tool in the marketer’s kit.

Courtesy Berlinische Galerie – Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur

Making one’s way around Bologna on foot, with its many porticoes, can in itself feel like a game where one must traverse a mazelike urban space. Across the eleven locations, the Biennale offered a range of exhibitions that riffed on the theme. Heinrich Zille (1858–1929) photographed a German fairground, around 1900, an early instance of public entertainment. Presumably this proto–theme park was a place to indulge in carefree fun, but this cannot be taken as a given, as the photographer depicted the games and rides there with an eerie sense of absence. At times, they resemble a noir film or a crime scene.

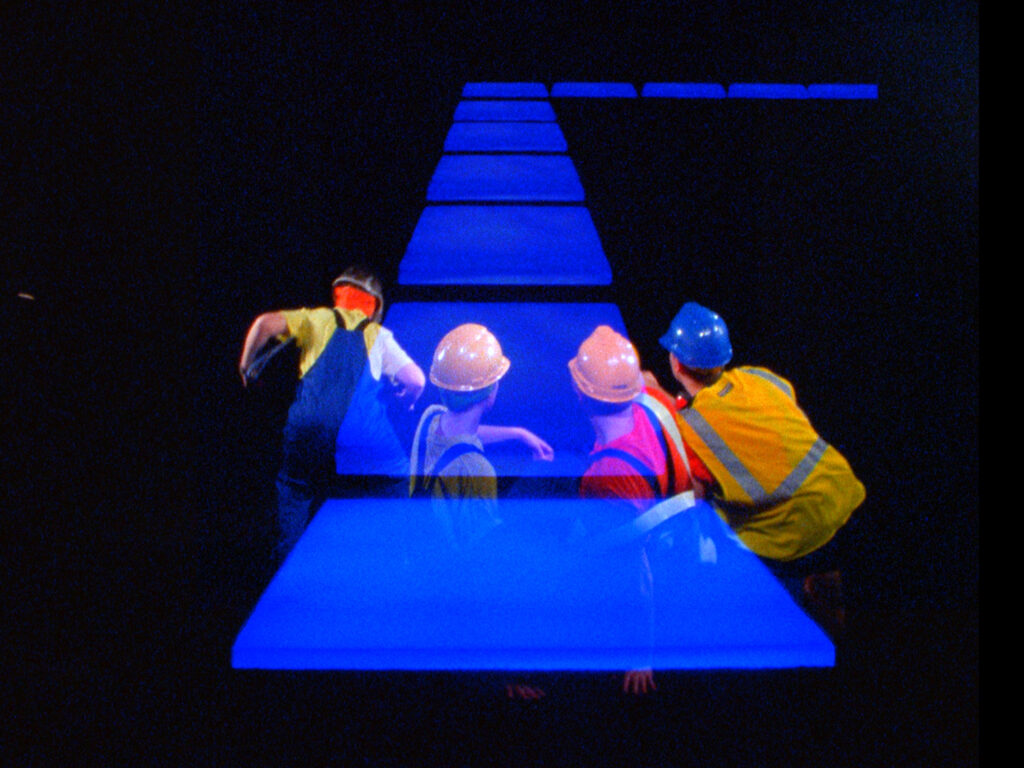

Public games are also seen in Olivo Barbieri’s early series, Flippers, from 1977-78, featuring pinball machines that he came across in an abandoned warehouse. He photographed not the location, but the details of these machines, decorated with illustrations from film and comics, markers of different cultural moments, designed to transport the player into imagined worlds of space travel or the American West. Ericka Beckman used one of the most iconic board games, Monopoly, as the starting point for a film that addressed real estate greed. Having lost her longtime studio in Tribeca to developers, Beckman channeled her frustration into an analog film with the look of a Devo music video. Of course, much gaming today exists online, or in interactive video games. Danielle Udogaranya’s series looked at bias within these games, and how the videogaming community might address racial inclusivity, and another exhibition featured experiments with automated image making by a group of students from ECAL/University of Art and Design, an art school in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Courtesy Erik Kessels, Sergio Smerieri

Photography naturally lends itself to play. Posing or mugging for the camera are as old as the medium. Playfulness tends to be most visible in photography’s more everyday forms, when the maker isn’t striving to make art or thinking about an audience. For years, Erik Kessels, through his project In Almost Every Picture, has given new life and form to found photography albums, turning them into clever books and installations that follow a single subject, trope, or typology. In Bologna, he presented a series of images made by a husband and wife, Carlo and Luciana, who photographed each other over many years while traveling the world. They pose in the same position as each other, in front of both iconic and ordinary sites: the Eiffel Tower, a nondescript Ibis hotel. The viewer knows that they are together, despite the fact that they always appear to be on vacation alone.

Courtesy the artist and Katharina Maria Raab Gallery, Berlin

Between 1994 and 2000, Hicham Benohoud was employed as an art teacher at a school in Marrakech. During that time, he worked with his young students to create an intriguing series of collaborative, performative portraits. In these seemingly simple, black-and-white images, the rules governing a school come undone. Rolls of paper unfurl from a wall. The classroom becomes a studio for improvisation and self-invention. The power of group creativity is unleashed in a kind of DIY theater. Props, costumes, and sets are improvised. Paper-tube appendages, geometrical streamers, precariously stacked desks—there is an art here of photography, but also of choreography and collaboration. The series makes a powerful case for play as the key ingredient in the creative process, and for how games—and arresting photographs—can be crafted from just about anything.

The sixth edition of the Foto/Industria Biennale was on view in Bologna, Italy, October 18–December 8, 2023.