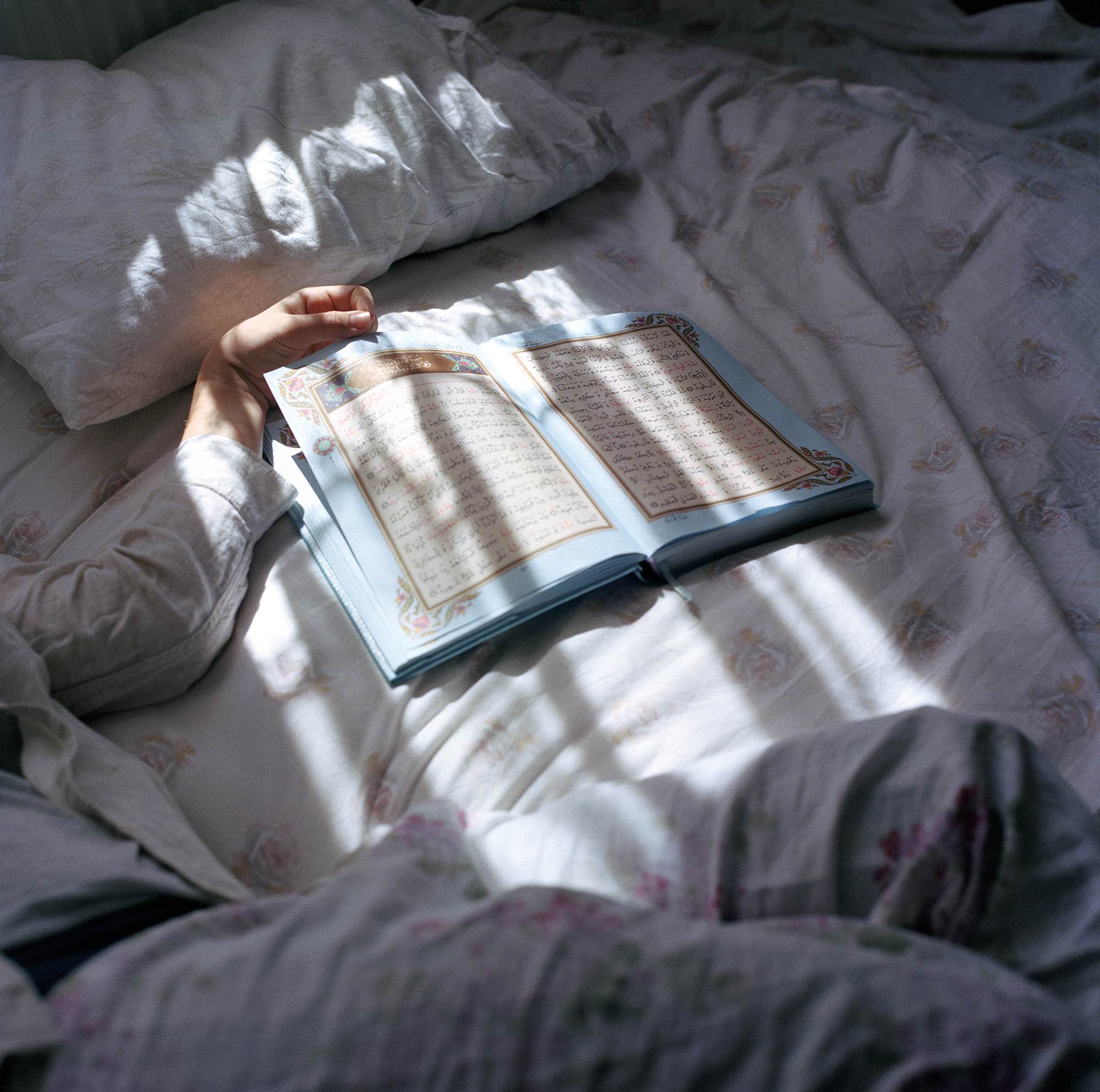

Sabiha Çimen, A student who has left the school mid-term waits for her father to pick her up, Istanbul, 2018

Sabiha Çimen was twelve when, in 1998, she enrolled at a hafiz okulu (guardian school) in Istanbul. Since 1970 more than 160,000 girls in Turkey, aged eight to nineteen, have studied in these single-sex schools, memorizing the Koran’s 6,236 verses, which takes around three years, and becoming protectors of Islam’s sacred book. Çimen’s upbringing made such a deep impression on her that, a quarter of a century later, these schools became the subject of Hafiz (2021), her first photobook. Intensely intimate, Çimen’s portraits, made between 2017 and 2021, surveil the double lives religious students lead in contemporary Turkey, where it is legal for parents to send children even as young as two years old to study at Koran courses.

Çimen belongs to an ethnically Kurdish Persian family. Her older sisters had gone through the same education, which was a rigid and traumatizing process; Çimen attended the Koran course with her twin sister. “I used to imagine these schools like prisons as a kid, but once inside, I saw I was mistaken,” Çimen, who was named a Magnum nominee in 2020 and has published her photography in The New York Times Magazine, Le Monde, and Vogue, told me last fall in an Istanbul coffee shop. “It was a vibrant environment. You couldn’t find such wise and bold women together anywhere else in the world.”

Studying there alongside six hundred other girls for three years formed a large part of Çimen’s DNA. But on graduation in 2001, Turkey’s headscarf ban postponed her plans to attend college. In those listless years, she became infatuated with photography. During an umrah pilgrimage in 2002 to Mecca, Islam’s holiest city, Çimen saw a Canon camera in a Saudi Arabian shop window. Over the next two years, she used it to keep a diary, making portraits of her mother and one of her sisters, and finessing her craft as a self-taught photographer. At college Çimen studied international trade and business, a field she had no interest in. She pursued a master’s in cultural studies, savoring Homi K. Bhabha and Giorgio Agamben’s texts, and wondering whether she should be a scholar. For her graduate thesis, she worked in Fatih, the Istanbul neighborhood where she resided, photographing Syrians who had once been dermatologists, engineers, and architects, but who now worked at kebab and barber shops.

In 2015, Çimen bought a secondhand, medium-format Hasselblad. Once assured of her technical competency, she searched to find a subject for an extensive project. “These memories from my religious- education days haunted me,” she recalls. One day, Çimen summoned up her courage, visited the school she had attended, and gave a presentation to the current group of girls proclaiming: “Like you, I was a student here, in 1998. Now, I have this project about which I don’t know precisely what to do. We’ll discover it together! Would you like to spend time with me?”

Girls reluctantly agreed. On the first day, Çimen placed her camera on a desk to acquaint the students with its features. She spent a fortnight with them, living in their quarters, eating lunch, hearing their stories, and mostly avoiding the teachers. She went on to photograph Koran schools across Turkey: in Kars, Hatay, Malatya, and Rize. “Those girls are bashful, and I struggled to earn their trust,” she says. “Those I photographed in Istanbul were more outward looking but harder to work with.”

Hanging out with the girls, Çimen witnessed their strict discipline. Reading novels was banned. Smartphones were out of the question. Girls went to sleep at nine at night and woke up at five with the morning call to prayer. “They were like recording devices, memorizing the Koran around the clock,” she says. Getting permits to portray their world proved a challenge. One mufti (religious administrator) bluntly murmured: “You can’t photograph Muslim women. It’s forbidden in Islam.” Undeterred, Çimen realized her dream.

Hafiz’s world is Dickensian, with gangs of girls abounding in its corridors. There are fragile girls, tough girls, playful and traumatized girls. They hide behind a locker, a curtain, or a palm leaf. They Rollerblade, tend roses, play hopscotch, hold dead fish, look at caged birds, pore over a loaf of bread, eat ice cream, perform at a religious play. They’re primarily daydreaming—something Çimen did often in her student years. She explains that Koran-school graduates retain “organic ties” to each other throughout their lives. When some of these girls showed an interest in photography, Çimen mentored them, giving tips on which cameras to buy and how to look for interesting subjects. “Incredible talents will emerge among them. It was fate that placed me here, and the same can happen to them,” she says. During the photoshoots, Çimen resisted lifting her camera and remained on the same level as her subjects. She gave girls the time and space to slowly open themselves up to her. While Çimen was photographing a wall at a Koran school one day, a girl asked: “Why don’t you photograph me instead?” This question became a turning point in what Çimen calls their “invisible agreement.” Afterward, on an outing, students spotted an exploded watermelon on the pavement—“I said: ‘Stop, girls! I want to photograph you around this watermelon.’ Having internalized my style, they soon began to gravitate toward things I like to put in my compositions.”

All photographs courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

I wonder who the audience will be for Hafiz, a poetic book that took Çimen three years to compile from three hundred images. Turkish photographers? Pious young girls? What will her book tell foreigners about their lives of religious devotion? “I wish that these kids and their families would be my audience,” muses Çimen, “but sadly, it won’t be them.” Out of Hafiz’s print run of two thousand, only one hundred books are in Turkish. “As for those Islamist men who have always been against me, never looked at my art and instead tried to ban it—they won’t be my audience either.” Yet Çimen seems fated to be a guardian for the young students whose experiences she shared and captured, serving as their hafiza—the Turkish word for memory.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the column “Viewfinder.”