A Screenwriter’s Forgotten Photographs of American Televisions

In the 1970s, Dennis Feldman photographed living rooms across the US. What do his images of TVs reveal about the national consciousness?

Dennis Feldman, TV (political show), San Francisco, 1977

In 1969, shortly after graduating college and returning home to Los Angeles, Dennis Feldman found himself photographing televisions. It was a time when TV organized the American home and society at large, pervading everyday spaces, public and private, and transfixing its consumers as the radio never could. There were three national networks and programming genres galore—quiz shows, soap operas, Westerns, situation comedies, sporting events, the news. Feldman, the son of a distinguished television and motion picture producer, grew up in Beverly Hills, and was a part of the first generation in history to be glued to the television screen, or any screen whatsoever, for essentially a lifetime. Since his family was among the first on the block to have a television set, kids from the neighborhood spilled into their home after school to watch the puppet program Time for Beany. He would go on to write in his epochal photobook American Images (1977), a project with a national scope in the tradition of Walker Evans’s American Photographs (1938) and Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958): “There is something overwhelmingly appealing to me about containing the world in one of those rectangular shapes—to live my life in one room.”

At the time, TVs were a site of both desire and anxiety, providing a magnificent portal to other worlds inasmuch as it confined vision to an addictive electronic box. By 1970, 95% of American households had at least one television set, watched on average for 5.9 hours per day. While the concept of “screen time” emerged in parenting discourse about TV in the early 1990s, becoming an unshakable cultural fixation with the rise of smartphones in the 2010s, the prominence and temporal demands of screens indeed dates to the postwar period. Children and adults were captivated by their television sets in ways not entirely dissimilar to our contemporary engagement with screen devices.

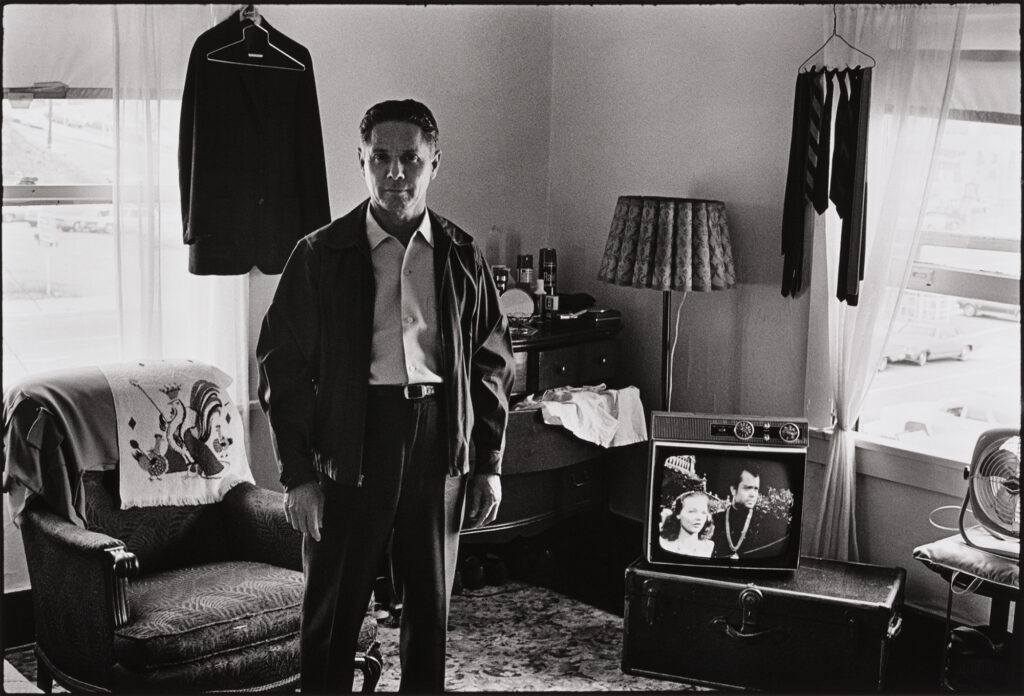

Feldman’s interest in TVs and the fantasies they propagated arose from a photography project he was pursuing after college. Visiting cheap residential hotels in the downtown Los Angeles district once known as Skid Row, he politely asked the inhabitants if he could both take their portraits and turn the camera around to record the other side of the room. Some agreed; others didn’t. For him, these impoverished dwellings symbolized his anxiety of being a failed artist; fear of withering away in one of those dreary rooms was what led him to photograph them. Because the individuals, down on their luck, were often watching TV, the second set of photographs he took almost invariably showed a boxing match or a rerun episode of The Lone Ranger, frozen in time. The process of finding subjects was reminiscent of his former summer job selling encyclopedias to working-class households in the Los Angeles suburbs. Though short-lived, the position taught him to knock on doors and cajole people into inviting him into their living rooms to recite his sales pitch. He drew on this skillset as he went door to door with a Leica.

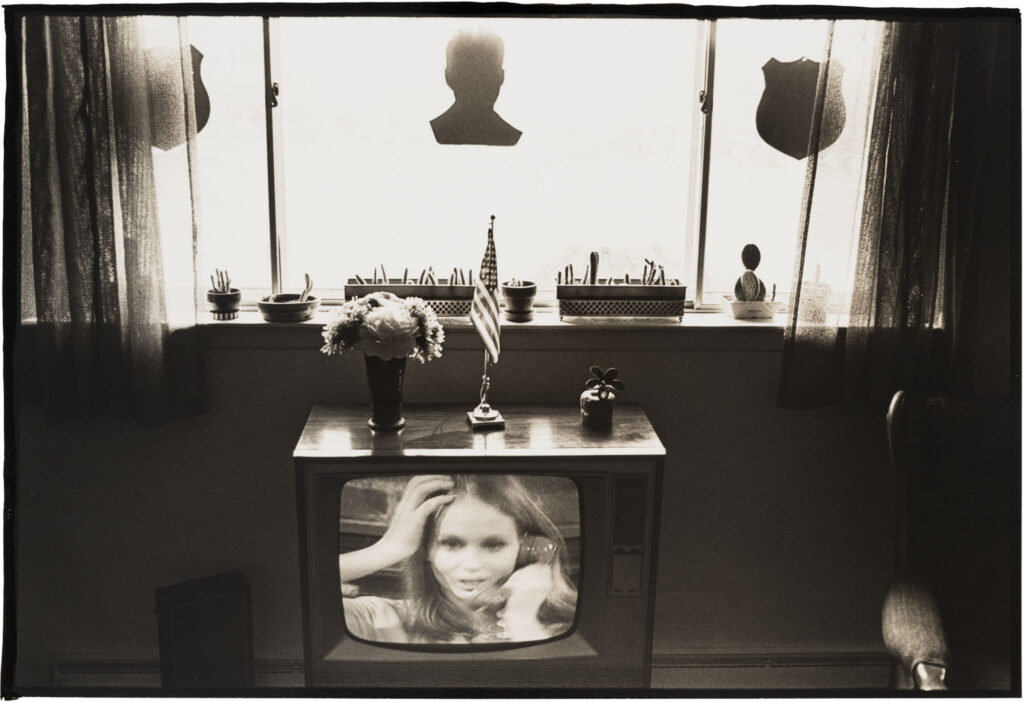

A committed documentarian, Feldman never manipulated the environment or took more than a few pictures total. He photographed each television set in the full specificity of its domestic setting, whether it served as makeshift shelf for prescription bottles or rested askance on a dirt-encrusted floor. In this respect, his photos contrast with the sterile, more decontextualized apparatuses of Lee Friedlander’s Little Screens from 1963 to 1969—a series Feldman was only marginally aware of. As he recently told me, “The interiors of peoples’ homes, the images they had in their homes, their clutter and disorder were a portrait of their mind, of their consciousness. And the TV was the national consciousness, generating images and words, dialoging characters. Those fantasies and realities . . . clashed, but they coexisted for that person in that moment.” Taken in Skid Row, a short drive from the Hollywood studios that pumped out irresistible visions of glamor across the country and around the world, Feldman’s photos couldn’t have laid bare this class discrepancy any more plainly.

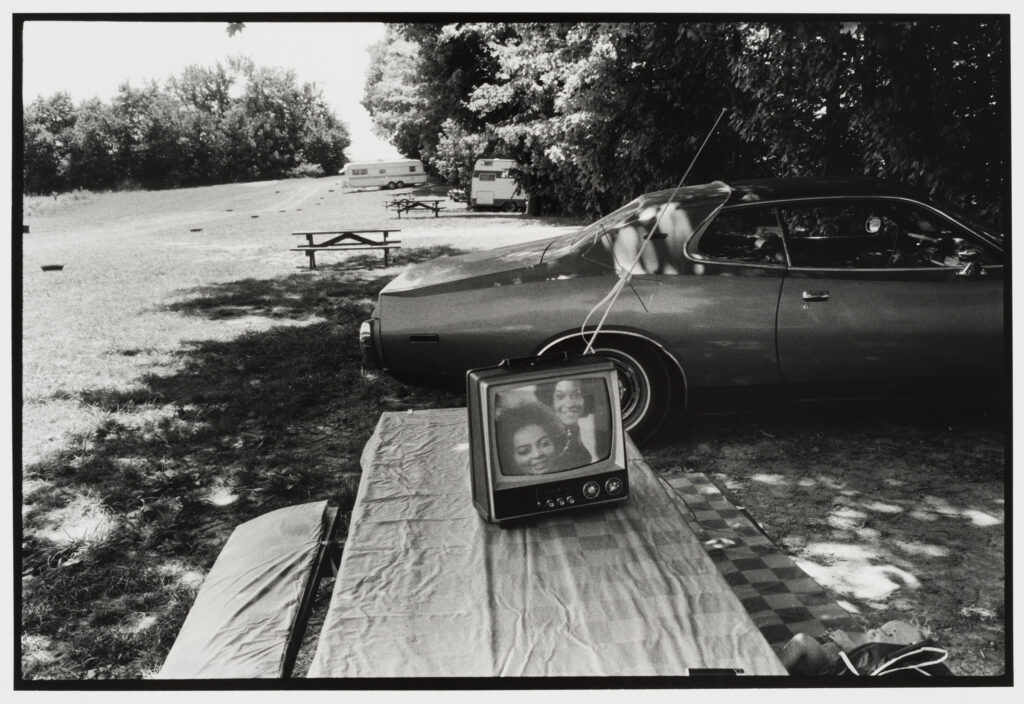

In 1974, Feldman traveled to forty-nine states with his then-wife Beverly, driven by his preoccupation with the national psyche along with his desire to emulate the storied trajectories of Walker Evans, his friend and professor during his graduate studies at Yale, and Robert Frank, an encouraging acquaintance. His mission was simple: to document disparate scenes of American life. Over the course of eleven months, the couple zigzagged around the country in a pickup truck with a shell on top, used a piece of plywood with foam as a bed, and heated up canned Dinty Moore stew on a propane gas stove. It was a far cry from Beverly Hills. When there was enough money for a motel room, Feldman covered the bathroom windows in tinfoil and developed dozens of pictures, many of them unsurprisingly involving televisions.

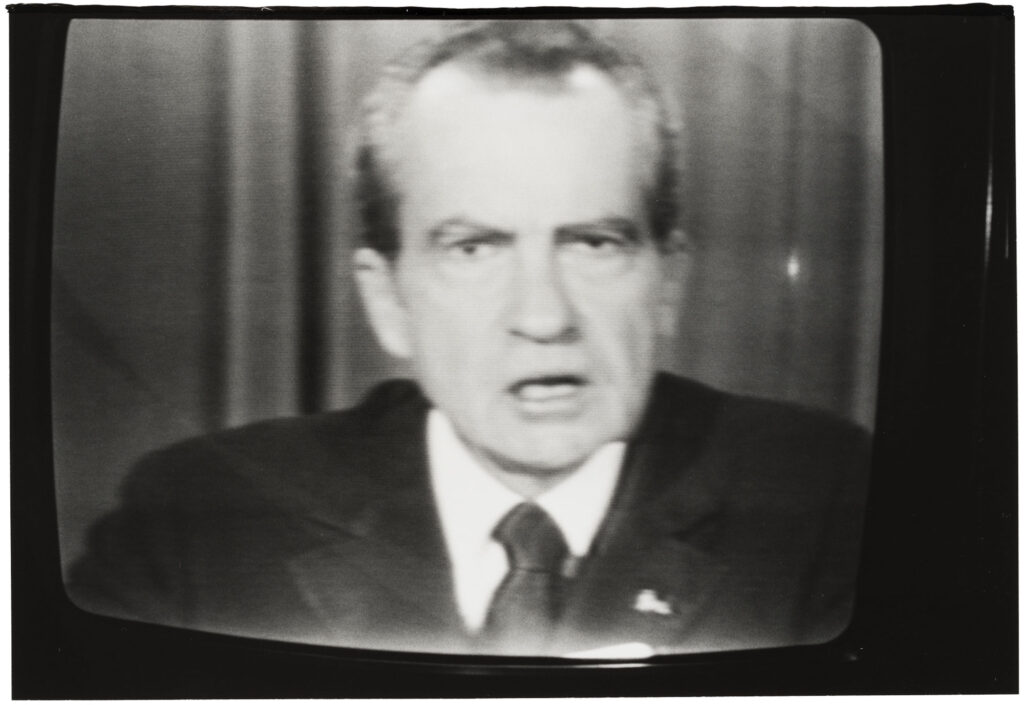

In a living room in Ellamore, West Virginia, he photographed a shirtless white boy who averts his gaze from the TV for an instant and looks suspiciously toward the camera. In a campground in Lodi, Ohio, he photographed a small TV perched on a shady picnic table, its screen conjuring two Black women with smiles plastered on their faces. In his own motel room in Springfield, Missouri, he photographed the live resignation of President Richard Nixon—the culmination of more than a year of publicly broadcast Watergate hearings that had engrossed the country. A screen decontextualized from its setting, as if to stress the event’s historical significance, the image was Feldman’s most frontal television portrait.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Harvard Art Museums

Across this TV series, screen time was not measured in the minutes and hours spent watching Orson Welles costume dramas or Mr. Whipple toilet paper commercials, but felt in the sheer quantity of bright surfaces that populated multitudinous environments and brought new imaginaries and affective arenas to public and private cultures. The series casts screen time as both an individual and a collective experience. “I saw every interior as a picture of the mind of the person(s) who assembled that space. A portrait by other means,” he told me recently. “And the one moving thing in the room was the image on the TV—the same national consciousness running in millions of different interiors.”

As a young photographer in the 1970s, Feldman had a rigid idea of what counted as a good picture and only printed and published a small number of television sets. But revisiting his contact sheets decades later, after a noted career in Hollywood as a screenwriter, film producer, and director, he found about two hundred television images spanning his travels from this period. The Harvard Art Museums recently acquired forty-one prints from the TV series, where, in late October, a selection of them were put on view—some for the first time, anywhere. After heralding a time of screens a half-century ago, Feldman’s photographs continue to question how prolonged encounters with them—and the fantasies emitted from them—have been reshaping the human subject.