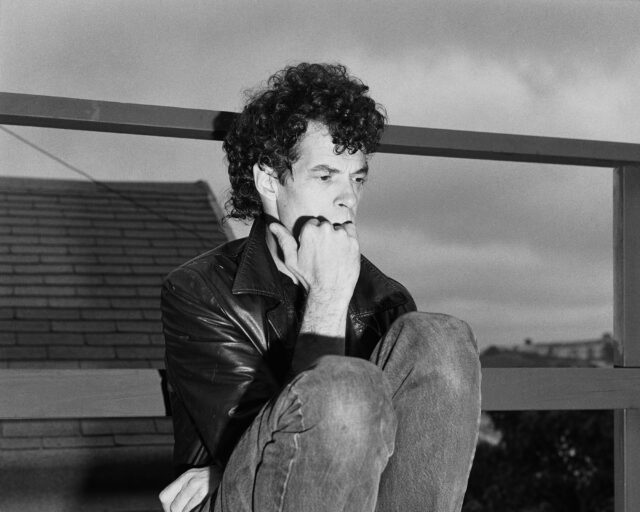

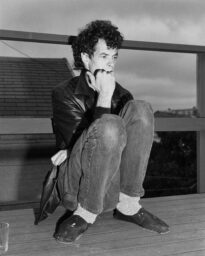

Jo Ractliffe at her studio in Fish Hoek, South Africa, July 2025

Photograph by Pieter Hugo for Aperture

The day I visited Jo Ractliffe in the coastal town of Fish Hoek on South Africa’s Cape Peninsula, low clouds obscured the valley over which her house looks, eclipsing any view of the expansive bay. In summer, and in the absence of the season’s infamous gale-force southeaster, the setting is idyllic. The town, however, is something of a suburban oddity. Once intended as a residential holiday resort, and historically dry (an obscure bylaw proscribed the sale of alcohol within its limits until recently), Fish Hoek has God and secondhand goods in surplus, with sixteen churches and half as many thrift stores. When Ractliffe moved there a decade ago, the population was neatly summarized in rhyme: “for newlyweds and nearly deads.” She was neither. The demographic has since shifted, with the arrival of “semigrants” moving from South Africa’s failing municipalities to the relative stability of the Cape.

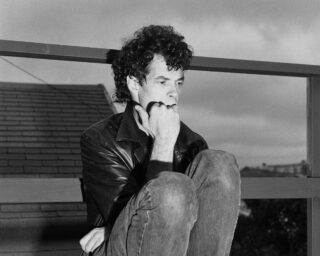

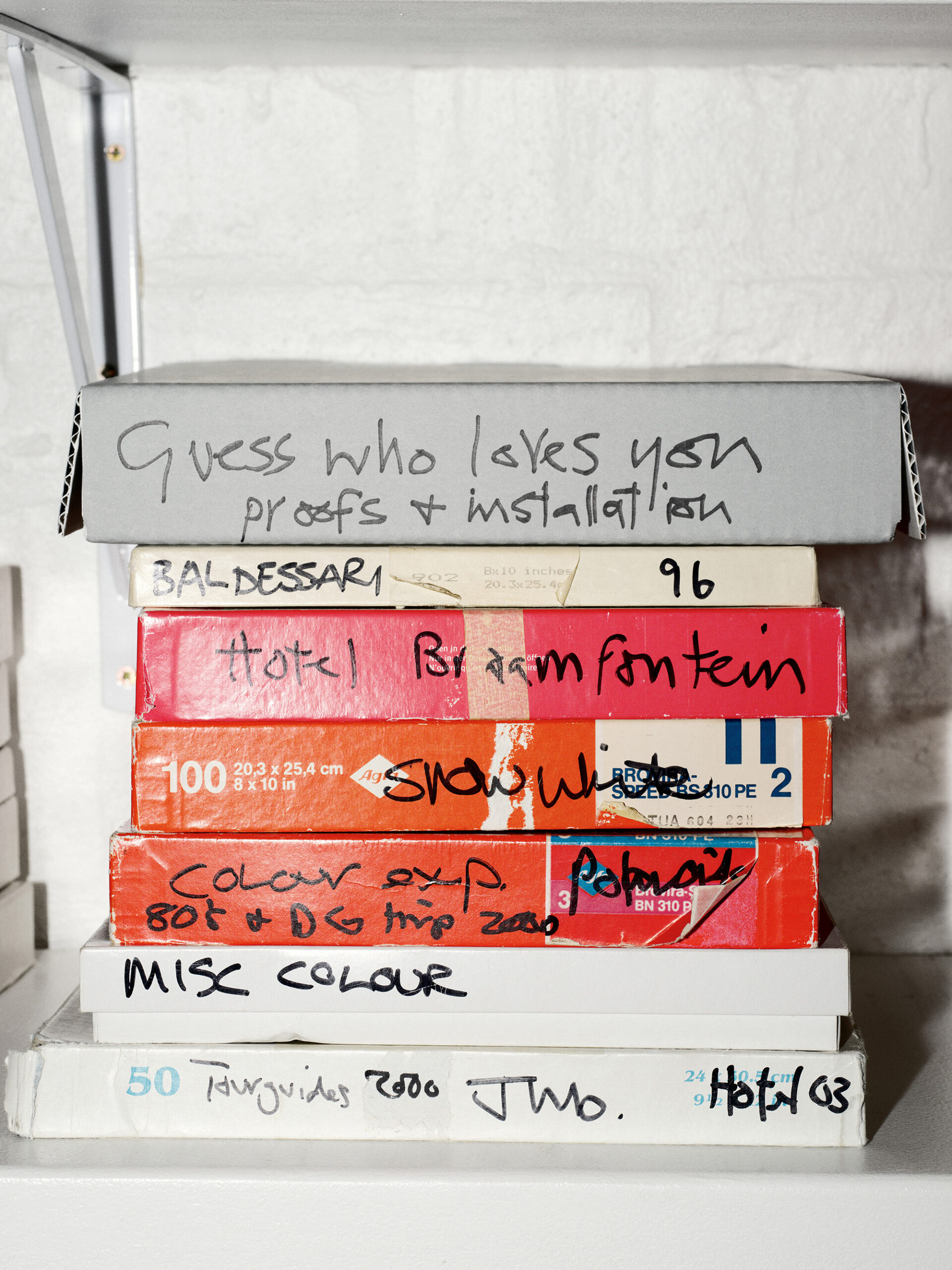

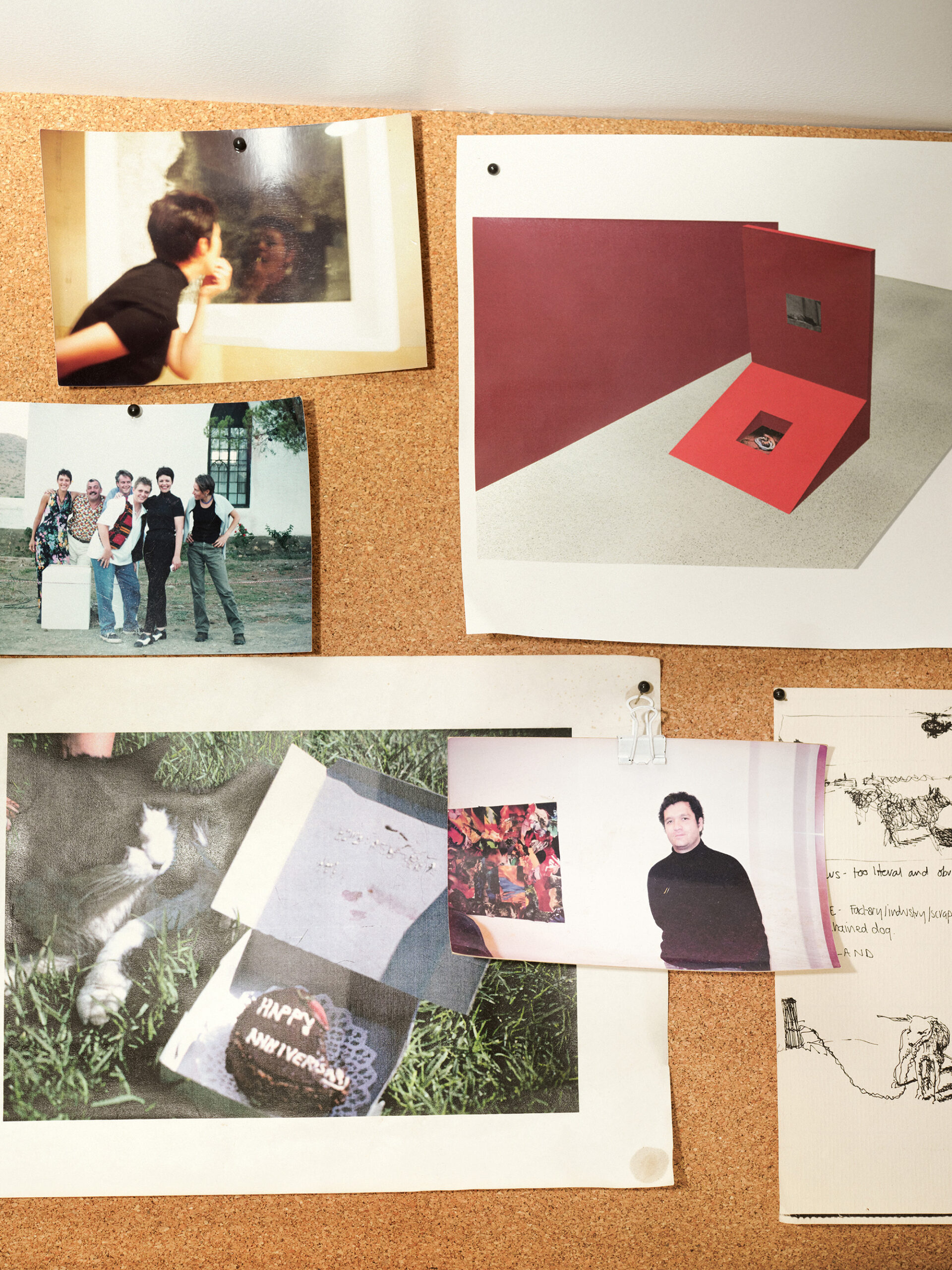

Photographs by Pieter Hugo for Aperture

Situated on the mountainside behind her house, Ractliffe’s studio was luminous against the day’s gloom, the white-plastered brickwork reflecting the diffused light from three large industrial windows. Black-and-white test prints for Landscaping (2023–24), a study of slow industrial destruction, were gathered on a white table. On a gray magnetic board were loosely arranged images from The Garden, commissioned for a solo exhibition called Out of Place / En ces lieux at the Jeu de Paume, the Paris museum, which opened in January.

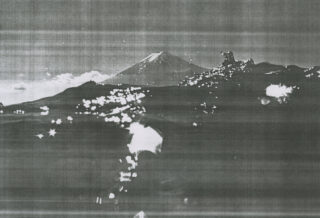

In cabinets that line the opposite wall, an archive of gelatin-silver prints traces her continued engagement with the mute traumas of the past latent in the present. Over four decades, Ractliffe’s focal point has been not the spectacle of violence but its aftermath—absence as evidence—as in her oblique documentation of the Angolan Civil War in Terreno Ocupado (Occupied Land, 2007) and As Terras do Fim do Mundo (The Lands of the End of the World, 2009–10), where seemingly “empty” settings are revealed by their captions to be sites of conflict, death, and dispossession.

Above the studio’s cabinets, four words are hand cut into the topmost bricks: WERK, TREK OF VREK (“work, move on or die” in Afrikaans). These were made by an artisan in a small Karoo town along the national highway featured in Ractliffe’s “inventory of the road,” as she describes NI: every 100 kilometres (1996/99), and near where she photographed the dead donkey in End of Time (1996/99) that has become a symbol of all the implied yet unpictured violence in her photographs.

Over four decades, Ractliffe’s focal point has been not the spectacle of violence but its aftermath.

In the week before my studio visit, Ractliffe was burgled, her computers and photographic equipment stolen. The event was reminiscent of a previous burglary, in 1990, that proved formative to her practice. Unable to replace her cameras at the time, she made do with a plastic toy the thieves had disregarded: a vintage Diana camera. To Ractliffe, the resulting images—darkly vignetted, murky, imprecise—reflected something of the uncertainty preceding South Africa’s first democratic election, in 1994, and worked against the assumed transparency of the social documentary tradition. “That burglary was a perverse bit of luck,” she said in a 2020 interview with the collector Artur Walther. “It gave me a new tool to work with photographically.” The Diana survived this recent break-in too.

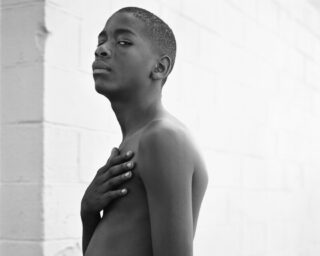

© Jeu de Paume

Ractliffe’s studio hews closely to the one designed for her Johannesburg home, where she lived for twenty-five years beginning in 1990: a generous, gable-ceilinged space with a darkroom at one end and a storeroom at the other. Originally from Cape Town, Ractliffe returned to the area in 2015, nine months before she sustained a debilitating injury. The Fish Hoek studio doubled as a physio’s office (a Pilates reformer is still kept beneath a worktable for occasional use), while the darkroom was relegated to a second storage space until nearly a decade later when, at the end of 2024, the artist made her first analog print for Out of Place—the Paris show.

Curated by Pia Viewing, the survey offers “a different way of looking at my work, beyond the idea of ‘landscape,’” Ractliffe said. “Often, my photographs are understood as spaces of violence untethered from place—they become something strange and abstract. But for this show, we’re anchoring the images to their settings.” Toward this specificity of context, the exhibition includes more than a hundred previously unexhibited photographs, “expanding an understanding of both my practice and places that I have been repeatedly drawn to.”

As a tender counterpoint to these many overlooked and “leftover” spaces, The Garden centers on a cast of self-possessed protagonists—keepers of backyard lawns, arrangers of rockeries, composers of salvaged bric-a-brac, amateur horticulturalists, and land activists—set in the bleak terrain of Ractliffe’s perennial subject, South Africa’s West Coast. While incidental figures appear in her images of peopled places, few of her posed photographs have been published (indeed, she has long expressed discomfort at making and sharing portraits).

For this new work, however, portraiture felt imperative. “I have to contextualize them, their specific stories,” she said of her subjects. “They’re the makers of these extraordinary spaces.” Showing me pictures from The Garden, Ractliffe recounted an anecdotal history of these marginal spaces pitted against the harsh South African environment she knows well: “It’s windy as hell. Nothing grows. The light is unforgiving.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 261, “The Craft Issue,” under the column Studio Visit.