The American Dream in Saudi Arabia

Ayesha Malik, Suha after work in the commissary parking lot, December 2011

© the artist

In Ayesha Malik’s first book, ARAMCO: Above the Oil Fields, few of her photographs show rigs, pumps, or other industrial equipment. Instead, she presents smiling families, golfers, palm trees, verdant landscapes, Christmas lights, and picnics—all through “a dusty-rose filter,” as she describes in the preface. Malik spent her childhood in Dhahran, an American enclave built exclusively for Saudi ARAMCO employees in the late 1930s. Inside the compound, which was modeled after a California suburb, families from around the world send their children to American schools, play baseball, and speak English. Women are allowed to drive, and wear Western clothing. Here, cultures that usually clash blend together, and identity outgrows simple, nationalistic terms.

Only months after the U.S. enacted a travel ban on residents from seven Muslim-majority countries, Malik and I sat down to discuss the complications of cultural identity and the power of compassion.

Ayesha Malik, Early-morning view along Rolling Hills Boulevard, November 26, 2016

© the artist

Annika Klein: ARAMCO: Above the Oil Fields includes old family snapshots, which are laid out in the same way as your own photographs, floating on the page with captions in the back. Why did you decide to organize the book this way?

Ayesha Malik: While laying it out, I wanted it to be genuine and intuitive, and not based on what people might expect to see. I thought a lot about my own memories in Dhahran and how I felt connected to the people I photographed; I saw a little bit of myself in them. Growing up, my dad took snapshots of our lives. I imagined how these kids felt similar to how I did. Not much changes in Dhahran. The old pictures create an atmosphere of nostalgia and a space for readers to think about their own memories.

Ayesha Malik, Baseball player in the dugout, October 21, 2016

© the artist

Klein: You said the word “genuine.” But when I think of something like a corporate compound, or even a suburb, I think of it being artificial.

Malik: In art school, while making work, I remember somebody using the word “theatrics.” And it was funny because it is theater, in a way. But it was my life, my normal, my “genuine.” The cookie-cutter houses, the manicured grass were artificial, but the life I led was not.

I don’t think anyone in the ’30s could have predicted what would come out of this manicured environment in Saudi Arabia. If you go deeper into ARAMCO’s history, there is a story of human connection, but that isn’t always true. Its history is not without faults, as in a promotional film from Standard Oil of California circa 1948, titled Desert Venture. Aspects of the film reinforce orientalist and neocolonialist stereotypes. The relationship has evolved and grown. Most Aramcons are mindful of those stereotypes. Of those who aren’t Saudi, many actively try to learn about and respect Saudi culture, integrating it into their lives. In ways seen and unseen, it becomes part of who they are. People spend lifetimes there. My family did.

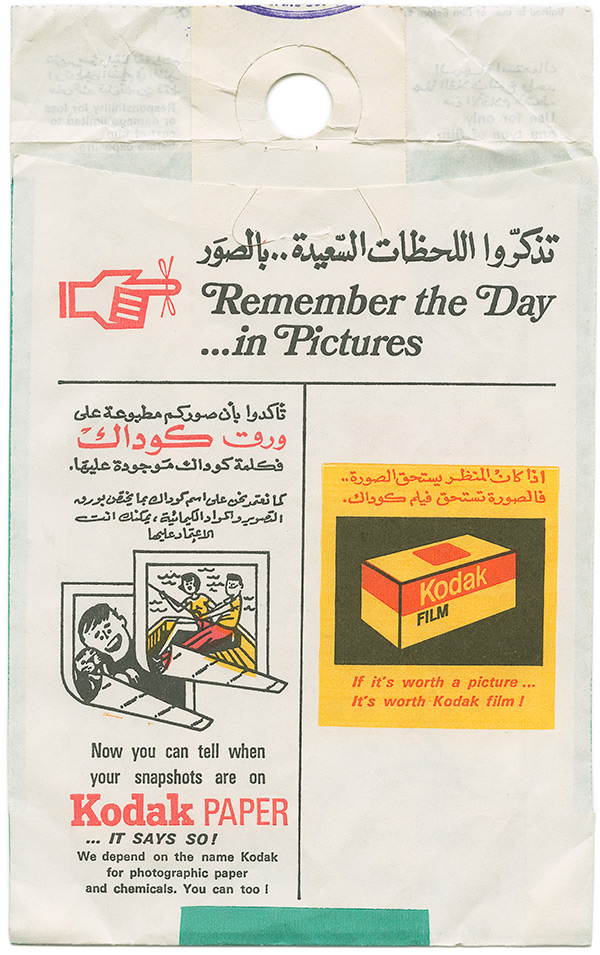

Ayesha Malik, Kodak envelope, ca. 1980s–90s

© the artist

Klein: Along with vintage family photographs, you also include ephemera, such as Kodak envelopes with and film receipts. One of the most memorable examples is a hilarious, charming fan letter that your sister wrote to Leonardo DiCaprio. How did you decide which archival documents to include?

Malik: The Kodak envelopes, for example, are familiar to many Americans, but they’re probably not familiar with the Kodak envelopes with Arabic writing. It creates a psychological space for the work and also a physical memory. Looking through this book and touching these inserts, the reader will probably feel like they’re looking through my personal stuff, which is intentional.

I use my sister, Sara, as an example throughout; the fan letter is a moment of humor. Many girls here experienced similar emotions as teenagers, and I like the fact that she explains, “Oh, in Saudi Arabia, no one comes here.” We had a movie theater that played old movies and huge sections would be missing. The censors would cut out the whole kissing and romance scenes, and we were left wondering, Why is this movie over in twenty minutes? What happened? Now, access to Western media has changed because of globalization and the Internet. But, at that time, I longed to watch Western films, and I really wanted to go to the States. When we would visit, the first thing we’d do was get junk food and watch bad TV.

Ayesha Malik, Aramco mom, December 2011

© the artist

Klein: How would you describe your nationality? How does the theme of identity play into your work?

Malik: My dad would identify as American because he spent a long time studying, living, and working in California. We’re ethnically Pakistani. I’m not necessarily Saudi by nationality, or by blood, but it’s a huge part of my identity. I’m American according to my passport, but, sometimes, when I’m in America with kids who’ve never left the country, I feel different from them. Then, when I’m in Pakistan, I feel American. Sometimes the technicalities of identity are flawed because how you identify yourself is usually more complex than what people see.

There are many Saudi women in this book, but some of the portraits don’t visually say “Saudi”—or what we are trained to understand “Saudi” to be. Newspaper and magazine editors often won’t choose those images where Saudi women aren’t wearing veils because they don’t see Saudi—they just see nothing. To some, this suggests a loss of culture or identity to a more a homogeneous image. We crave these obvious signifiers of identity because it lets us consume people and cultures like any other commodity. I was asked, for example, for a photograph I had taken at ARAMCO’s private beach. The person described it as the photograph of Western and Muslim women. It was an awakening moment. I thought, well, those aren’t necessarily two separate entities. I am both Western and Muslim. Who is to say, in that photograph, that the women in bikinis aren’t Muslims or that the women in abaya aren’t Western? It is all speculation. Images always fail to tell whole stories and express identities. I stopped using that photograph because I realized it plays into a stereotype.

I also remember a man looking at one of my photographs and saying that the woman was wearing a symbol of oppression (the abaya) and holding a symbol of freedom (a smartphone). He was a seemingly modern, left-thinking guy. To me, that is a problematic way of thinking. It is simplifying and divisive. We need new ways of seeing and interpreting.

Everyone is always looking for that perfect image to illustrate it all, and I don’t think it exists. I don’t believe in the nice neat package of identity. I hope that the ephemera and the text included encourages people to reconsider what they think they’re seeing. Throughout the book, I’m asking people to stop and think, What are you seeing? Are you seeing this American town, or are you seeing something that’s more complex and nuanced than that?

Ayesha Malik, Sprinkler rainbow on Tarut Drive, October 20, 2016

© the artist

Klein: Looking at these rosy pictures reminded me how rare it is to hear about the positive things that come from Saudi oil, especially in left-leaning, Western circles. The oil boom seems to have improved many lives in that region, at least on an economic level. On the other hand, the leaflets included in the book tout oil production as an unequivocal good, which does not account for the ecological ramifications. What are your views on the effects oil has on the environment?

Malik: I know from my father that, when he worked on projects, environmental protection was always considered. I became more conscious with age and the increasing mainstream media coverage of the ecological effects of oil, global warming, and climate change. There is no denying the childhood Dhahran gave me and so many other kids. My experience was very “rosy,” as you described it. But I do have an issue with the negative impact drilling for oil has had on the earth. It has come at a cost.

It is worth noting that Saudi ARAMCO is part of an initiative with the state of Saudi Arabia called Vision 2030, which aims to reduce dependency on oil by looking to new economic sources and developing different sectors, part of which includes renewable energy. ARAMCO is also helping fund artists who are talking about the impact of oil on society, cultures, and the environment, such as Saudi artist Ahmed Mater, who actively criticizes those consequences, and not just specifically in regards to Saudi Arabia. Those conversations have to be had, even it if makes people uncomfortable. And no, I didn’t receive any funding from Saudi ARAMCO.

Ayesha Malik, Mrs. Bumstead’s charm bracelet, October 21, 2016

© the artist

Klein: In your interview with Elizabeth Renstrom of VICE, included in the book, you mention that many kids growing up in the U.S. don’t have the same opportunity to live with people from so many different countries.

Malik: I grew up with people from around the world, and we would make jokes about the Palestinian kid, the Jordanian kid, the American kid, et cetera. Coming into the States, I realized people don’t always get those jokes. In Dhahran, if you embrace it all, I think you develop a sympathetic, empathetic worldview. Friends telling you about their parents in Syria, or their family in Palestine—those are the stories I heard growing up. It’s a way of seeing the world that’s bigger than what’s just around the corner.

Ayesha Malik, Tank farm, Saudi Arabia, December 24, 2012

© the artist

Klein: How does growing up in such an international environment make you feel about the recent wave of this anti-immigrant feeling, and particularly Islamophobia?

Malik: It’s scary, and it touches on the darkest impulses of society. It’s about as un-American as it gets. I’m Muslim. What are you saying about me and my family, and my family’s family, and the people I feel connected to? They’re just regular people building their lives. It feels like a personal attack. Empty, stereotypical statements—they make me angry. You can’t color any group of people.

ARAMCO: Above the Oil Fields was published by Daylight Books in 2017.