Attention! Photography and Sidelong Discovery

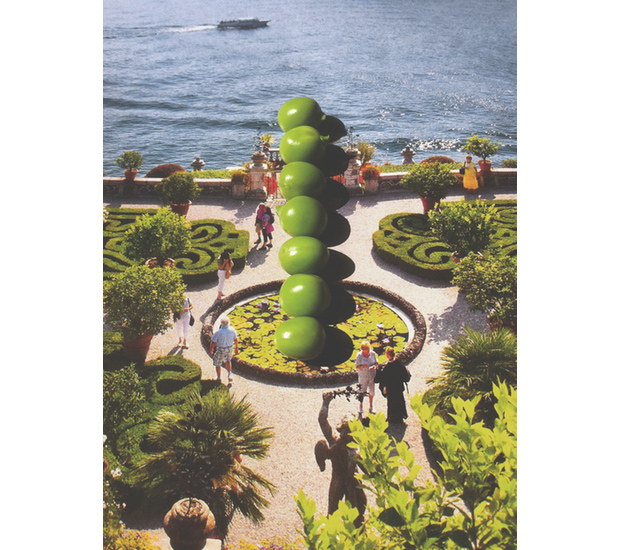

Nina Katchadourian, Topiary, from Landscapes, part of the series Seat Assignment, 2010 and ongoing. Courtesy the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco.

Curiosity is an oddly ambivalent word that historically has pointed almost as frequently to a condition of ruinous distraction as to a state of intense and productive concentration or to an urge to discover. To be curious or to be interested in curiosities is to be charmed by details, trifles, niceties, or subtleties, and to disregard fundamentals. Distraction has its uses, however, as the history of detective fiction tells us. In Edgar Allan Poe’s “ The Purloined Letter” (1845) the stolen object fails to reveal itself to the most sedulous searches; the suspect’s apartment is investigated long and hard, the walls and carpets peered at through microscopes, the furniture probed with needles. The very cobblestones in the courtyard are prised apart, to no avail. At length, Poe’s detective Dupin discovers the thing, tattered but undisguised, on a letter rack in the rooms of the minister who has stolen it. Dupin’s distracted, sidelong mode of attention has won out over the prefect of police and his zealous and methodical program of close inspection.

Poe’s prototypical sleuth springs easily to mind when considering the role of curiosity in photography, past and present. And once we have thought of Poe it’s a safe bet that somebody will invoke Walter Benjamin’s comment about the photograph looking increasingly, in the twentieth century, like the scene of a crime. This last is a conceit that does not apply only to photography’s evidentiary potential: it’s of a piece with the idea that the photographer sees more intensely into the heart of things, but also reminds us of all the lures and feints that he or she might employ to frustrate that assumption. The melodrama of appearance and reality conditions much of our thinking about photography and what it discovers about the world. But there’s another sort of photographic curiosity, something like Dupin’s state of oblique diversion or attention to the humblest, most fleeting scraps of the made world and their abject, slapstick, sometimes delicate poetry.

Consider Making Do and Getting By, the photographic series that British sculptor Richard Wentworth has been producing since the 1970s, and which amounts at this point to an archive of found semi-sculptural interventions in the fabric of the everyday. Many of them (as in Poe’s tale) involve scraps of paper slotted or crammed into slits and crevices. There are napkins and newspapers jammed under café tables, bits of cardboard or tape holding things together, or nearly. Wentworth is fascinated by how the ordinary world around us has been made—step into a London street with him and he will spin a narrative out of the history of manhole covers—but also by the materials we append to our surroundings by way of repair or warning or inadvertent decoration. Making Do and Getting By includes numerous curbside assemblages designed to keep drivers out of parking spaces: hulking agglomerations of old gates and busted chairs, or sparse but informative settings of bricks and broken plaster balusters. Elsewhere, the stuff superadded starts to assume the form and substance of its support, of a surface or structure that now serves as temporary storage: discarded paper cups seem to sprout like spring buds from the pipe they’ve been jammed behind; scribbled notes on somebody’s palm bleed into the hand’s lines; and a lost leather glove stuck on black metal railings takes on the spiny structure of the railings and the foliage in the background. Wentworth alights time and again on those moments when forms and substances transmute into each other, and the most incongruous additions seem organic outgrowths of ordinary infrastructures.

Richard Wentworth, London, 1994. Making Do and Getting By, 1999. Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery, London.

There’s something of Wentworth’s capacity for simply noticing things in Nina Katchadourian’s photographs; the two artists share a knack for spotting ephemera crushed in the street: a driver’s license plate (Wentworth) or an old music cassette (Katchadourian) so completely flattened by traffic that it has become a mere phantom stain on the asphalt. In fact, Katchadourian, whose hugely various work includes sound, video, installation, and performance, has described her art as precisely a process of noticing—of paying more attention to the world than the rest of us do. Her skewed sense of curiosity is to be seen, for example, in her long-running series Sorted Books, begun twenty years ago, in which the titles of books in a given library compose scurrilous or touching found poems, jokes, and legends: in one tellingly summarizing image from 1996, two volumes have come together to say: “What Is Art?/Close Observation.”

It’s a tendency that finds some of its keenest, and funniest, expression in Katchadourian’s Seat Assignment: a series of photographs—latterly also video and sound—made entirely in flight, with her camera phone. A subset of this series found unexpected celebrity in 2011 when her group of Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style were taken up by mainstream media outlets such as the New Yorker and even Oprah Winfrey’s website. (In March 2010, she spontaneously tricked herself up in an airplane bathroom, using tissue and paper toilet-seat covers, as a figure out of Flemish portraiture; many more such images followed.) But the admittedly hilarious Flemish pictures are just one small part of a much larger corpus of curious improvisations. In more recent images, for example, two small figures train a telescope on a night sky dominated by a salt or sugar constellation, and ectoplasmic clouds obscure photographed faces. The series has begun to splinter into more subseries—Landscapes, High-Altitude Spirit Photography, Creatures, Athletics, Disasters, even Top Doctors in America—all made with in-flight magazines, airplane food, and the crude lighting effects available at Katchadourian’s aisle seat.

Nina Katchadourian, Bather, from High-Altitude Spirit Photography, part of the series Seat Assignment, 2010 and ongoing. Courtesy the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco.

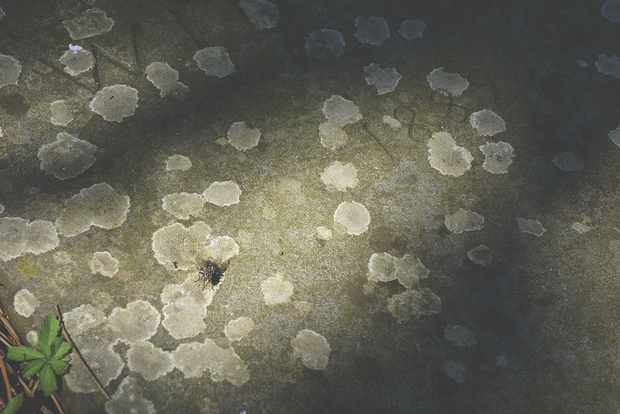

The comic register broached by Wentworth and Katchadourian feels light, almost frivolous, but it has something profound to say about the effort and pleasure involved in breaking habits of looking or not looking, of paying a new sort of attention. (I suspect that part of the appeal of Seat Assignment is in our envy that Katchadourian is the one person on the plane not bored senseless.) One version, philosophically speaking, of that process is summed up in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s definition of the aim of his discipline as “to show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.” The aphorism ghosts British artist Jeremy Millar’s 2012 photograph of a fly on Wittgenstein’s grave in Cambridge, England. No doubt Millar, whose videos, photographs, and installations frequently address modes of museological or archival looking, knows that Wittgenstein’s fly is an ambiguous creature: natural curiosity has got the insect into trouble in the first place, and it takes some rigor and self-control to crawl back out to the other side of the glass.

The curious photographic impulse I’m trying to corral here is also capable of a kind of metaphysical facetiousness. All the works I’ve mentioned are as much about the boundaries of our native curiosity, the constraints in which we improvise our existence, as they are about acts of extreme concentration and discovery. There’s a cosmically scaled version of that comedy of ambition and overreach in Katie Paterson’s History of Darkness: a “lifelong project” (as she calls it) in which the Scottish artist is amassing images of darkness, sourced globally from observatories and laboratories and transferred to 35mm slides, that show vacant black fragments of the night sky or of deepest, emptiest space. The slides are exhibited in a box that allows them to be taken out and examined, and each is labeled with a date and location in the heavens; an offshoot of the project (with the same title) involves large-scale photographic prints, similarly void. We know or suspect, of course, that there is something beyond or behind the darkness shown there, but even the most prying look will not disclose it as we hold each slide to the light. It’s a lesson in the infinitude of human curiosity and its attendant hubris.

History of Darkness is just one of several of Paterson’s works that essay a cosmically laconic take on astrophysical discovery and the protocols of its recording. A 2007 work, Earth-Moon-Earth, involved translating the first movement of Beethoven’s “Moonlight” Sonata into Morse-code radio signals and bouncing it off the moon; in the gallery a player piano performed the piece—somewhat degraded during the transmission—as it returned to Earth. For The Dying Star Letters—like History of Darkness, a continuing project—Paterson is sent an email each time scientists note that a star has expired; she then writes a letter of condolence, directed for instance to a staff member at the gallery where the work is on display: “I’m sorry to inform you of the death of the star SN2011kd.” The piece composes an index of disappearances, the light winking out as previous discoveries vanish into the void.

As Poe’s Dupin tells us in another story, “Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), the best way to catch sight of a heavenly body is to catch it off guard by looking a little to the side—“it is possible to make even Venus herself vanish from the firmament by a scrutiny too sustained, too concentrated, or too direct.” An excess of application, in other words, may result paradoxically in a failure of attention, and the cure is an oblique curiosity, a faith in peripheral vision. (What is Paterson’s History of Darkness if not an archive of all that’s off to the side?) It’s an essential lesson, especially in an era when we like to guiltily accuse ourselves of regular failures of attention, dispersed as our minds supposedly are among digital distractions. The history of curiosity reminds us that accidents will happen, and instructs its contemporary adepts how to be waiting when they do.

Curiosity: Art & the Pleasures of Knowing, a Hayward Touring exhibition conceived in association with Cabinet, will be presented at Turner Contemporary, Margate, England, May 25–September 15, 2013. The exhibition will travel to Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery (September 28, 2013–January 5, 2014) and then to de Appel, Amsterdam (June–August, 2014).