Black and White America

© Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos

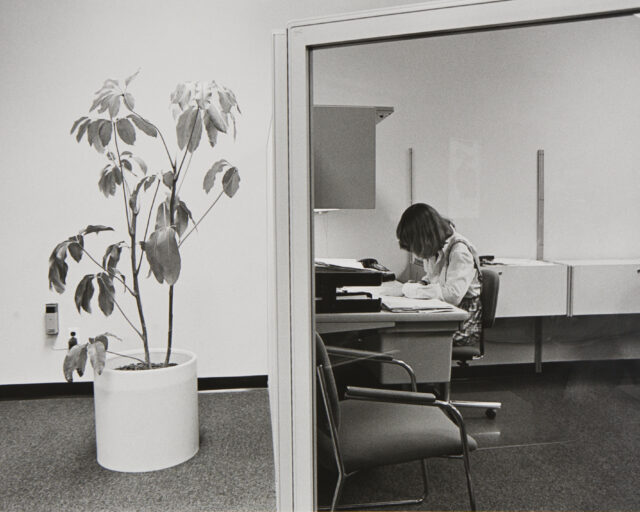

A young black man in a schoolboy hat playfully grabs a loved one’s chest from behind. The ground is wet, the lighting even, and people move joyously through the warm rain. A brass marching band walks in tow. When the white photojournalist Leonard Freed captured this scene in 1963, he had already been working as a freelancer for several years, accepting commissions from magazines like the Sunday Times Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, and Stern. Especially invested in the lives of black Americans, he photographed communities around the country in the 1960s, eventually using much of it in his landmark photo essay Black in White America (1968).

By the mid-’60s, Louis Draper, a black photographer from Virginia, had also become experienced with portraiture. Draper moved to New York to pursue photography, studying with well-known humanist photographers like W. Eugene Smith and Harold Feinstein. He occasionally received commissions from black magazines like Essence, and in the early ’60s, he exhibited twice at photographer Larry Siegel’s short-lived Image Gallery, then the only photography gallery in New York. Opportunities in the mainstream arts community were few and far between, however, due to discrimination. To promote artistic critique and community, he created a new space, the Kamoinge Workshop, the first black collective of photographers in the United States. It exists to this day.

© Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust

Even though these two photographers most likely never met, the exhibition Black in America: Louis Draper and Leonard Freed, currently on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art, surveys relationships between their bodies of work. Curator Barbara Tannenbaum shuffles photographs by the two artists into clusters that show how everyday acts, the media cycle, and activism affected the visibility of black Americans during the civil rights era.

To carry this out, Freed always ensured that his work traveled with context. The title of his photograph They are dancing at a jazz funeral in the streets of New Orleans, Louisiana uses the third-person plural and the term “jazz funeral” (not typically used by people from New Orleans), which hints that this photograph is of interest to his audience because it shows a ritual that departs from the somberness of white American funerals. During “jazz funerals,” solemn music is played during the procession from the house of the deceased to a cemetery, but once the body is laid to rest, the band swells into swingier tunes. The youthful men in Freed’s photograph are swept up in postsepulchral, bittersweet emotion, momentarily hopeful despite the recent loss of a community member.

© Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust

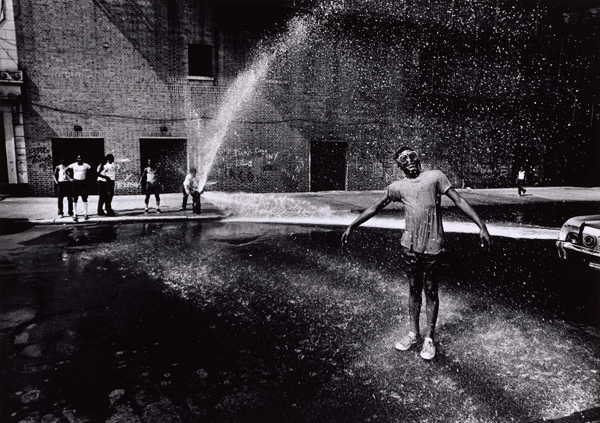

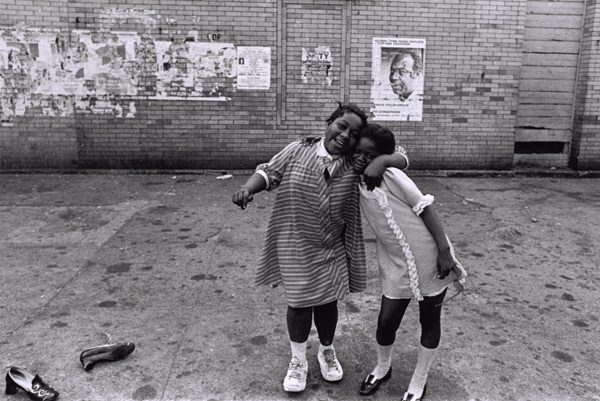

Showing a less candid and more cryptic sort of joy, Louis Draper created the photograph Girls Embracing, New York (1965). In what appears to be an alleyway, two schoolgirls grasp one another with unabashedly blissful expressions. A woman’s abandoned pair of stubby high heels lies mysteriously next to them. The brick wall behind includes a mangled patchwork of scraped-off posters—only one left intact; it shows a high-contrast image of activist James Farmer preceded by the words, “When this man moves … things change.” What exactly can be read in this interconnection between black female friendship, an absent older, female figure, and a political call to action? This ambiguity is characteristic of Draper. While Freed tends toward overt humanitarian messages, Draper creates a complex juxtaposition, placing a subject against a background of graffiti, billboards, or posters. Through Draper’s lens, the mass media’s coverage of the civil rights movement becomes the background of black New Yorkers going about their daily lives.

Draper occasionally traveled the mid-Atlantic region and abroad, though his practice was centered in his local community of Harlem. Instead of going to overt centers of political action like Freed, many of Draper’s images depict the action filtered through the local cityscape. He could capture moments of everyday life independent of a journalistic agenda, much in the vein of midcentury street photography. The photograph Harlem, New York (1960) shows a middle-aged woman with plum-shaped face waiting idly on the sidewalk. Strangers in trench coats stand close to her, others walk past, yet she peers out at the city as if she is totally alone. She is in transit, possibly thinking about the food in her sack, or whom she will share it with. Carole Kismaric, former editorial director of Aperture Foundation, described in the publication Exposure: Ten Photographers’ Work (1976) the solitude of Draper’s subjects who “revel in their privacy as they experience fleeting moments.” In most cases, a stranger with a camera would destroy any semblance of privacy, yet Draper is able to hold the solitude of his subjects. He maintains thoughtful silence when the time is right, choosing deliberately between privacy and direct interaction with subjects.

© Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust

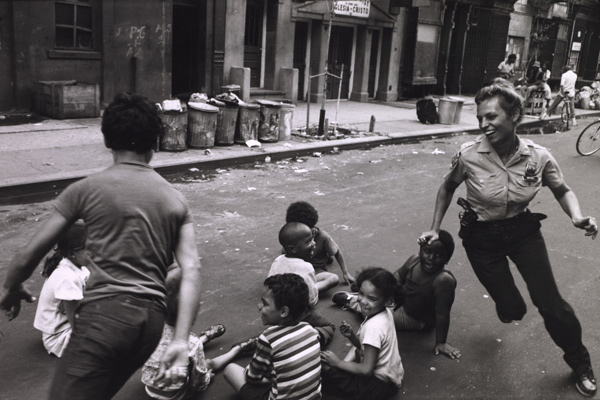

The depth of Draper’s portraiture has something to do with his careful attention to printing. As Kamoinge member Shawn Walker recollects, Draper’s photos were so skillfully printed that they are practically three-dimensional, lending his subjects an air of dramatic complexity. Freed also cared deeply about the production of his work, much more so than other harried photojournalists. Throughout his career, his wife Brigitte Freed (née Klück) served as his masterful printer. Still, he was expected to meet deadlines and pair his work with writing, sometimes creating work overshadowed by journalistic narrative. This occurs most forcefully in his photograph Black prisoners in an overcrowded communal cell in the Parish Prison-City Prison of New Orleans, Louisiana (1965). The incarcerated black men are photographed as silhouettes, with their arms extended through the cell into the light. While Freed is making an overt, well-intentioned critique of mass incarceration, he does so in a way that fails to highlight the people themselves.

© Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos

Despite their differing perspectives, it’s not immediately obvious who took which photographs in the exhibition. Which isn’t to say authorial identity doesn’t matter; when organizing exhibitions of civil rights-era photography, many curators fall prey to the idea that the race of the photographer isn’t of importance if the subjects are black. (And many fine art photography archives preserve the work white photojournalists made at black rights protests, but not those of African American photographers.) Black in America avoids this potential elision by featuring Draper, demonstrating the need for such curatorial evolutions—a particularly pertinent undertaking for institutions in the majority-black city of Cleveland.

How might an exhibition of black Americans during the height of the Black Lives Matter movement look fifty years from now? Certainly the roles of the fine arts photographer and the photojournalist will be entirely different. Politically, things may appear bleak, but one can hope that the democratic potential of camera phones and increased access to photography will create a new sort of archive. One that must circumvent mainstream media and fine art institutions altogether, giving black America what Draper once provided: an assured sense of privacy and a three-dimensional sort of beauty.

Black in White America: Louis Draper and Leonard Freed is on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art through July 30, 2017.