Reckoning with Canada's History of Whitewashing

Morris Lum, PA-1599-114-31, 2018, from the series Subtle Gestures, 2017–18. Stan Wong and Lou Wong wearing Western clothing at barbeque, Calgary, Alberta, April 8, 1969. Photograph by Ken Sakamoto, Calgary Herald

Original photograph courtesy Glenbow Museum, Calgary, and Calgary Herald

How do institutional archives create national narratives? On the occasion of Toronto’s month-long photography festival, Gallery 44, an artist-run nonprofit, asks just this. The curator, Gabrielle Moser, an assistant professor at the Ontario College of Art and Design University, focuses on settler–colonial image-making and its resistance. Moser brought together five artists, all with ties to the Canadian state, whose works rupture the welcoming, tolerant, multicultural story the country likes to project. Rather than pointing out what’s missing from institutional memory, these artists bring to the surface what is already there, but has been misread, misinterpreted, or misrepresented.

Deanna Bowen, a Toronto-based interdisciplinary artist, appropriated footage from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) with the intent of demonstrating how that reporting served Canada’s desire to show itself as tolerant and multicultural. The footage relates to Bowen’s own family, former enslaved people and their descendants, who fled all-black towns in the United States in the early twentieth century and found themselves in Northern Alberta. Bowen’s colleague Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn, who grew up in Montreal and now lives in Stockholm, has been mining the nearly five-hundred photographs her great-grandfather brought from Vietnam. The differences between his album and the Vietnamese art holdings of North American and European institutions reveal divergent values and hierarchies. Both projects are the result of ongoing investigations of and engagement with the radical potential of archives. Bowen and Nguyễn discuss these topics here, accompanied by the curator, Moser, who draws parallels between their works.

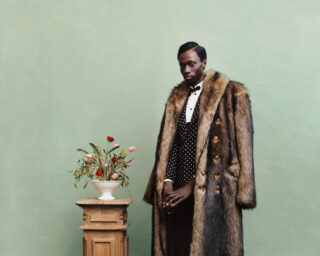

Jacqueline Hóang Nguyễn, Untitled, 2018, from the series Presence in Absentia. Sand. Installation at Gallery 44, Toronto. Photograph by Darren Rigo

Courtesy the artist and Gallery 44, Toronto

Laurence Butet-Roch: Archives often conjure up images of an austere environment to which only a select few, usually members of the privileged and ruling white patriarchy, have access or a demonstrated, vested interest. How did you, whose identities intersect a variety of marginalized communities, come to see their artistic and disruptive power?

Deanna Bowen: I’m a super sentimental grandkid of a family that has always been very much preoccupied with history in one way or another. A lot of what I’ve been doing for the last twenty odd years has been about making sense of that. Once one starts doing genealogical work, all these other historical materials appear and become intrinsic to understanding who those people were and who their community was. It was a doorway into grasping the ways in which trauma impacts the telling of our story.

Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn: I come from the other end of the spectrum. I grew up in an environment where family history was never talked about. It was always hush-hush. As new immigrants, we feel that we shouldn’t look back. Rather, in order to be the “model minority,” we ought to be looking forward, investing at all cost in the education of the children, who would then ensure the future of the family through their professional success. So I came to archives much later in life and not by way of the personal. In 2012, I started investigating the world’s first UFO landing pad built in the Prairies of Alberta in 1967. Looking for context, I did research in the national archives and library in Ottawa, as well as in private archives. I was struck by how white they were. It was especially surprising because 1967 marked this paradigm shift in the country from a privileged Northern European migration to the implementation of the points-based system, where an applicant can gather points in different categories such as education, language skills, age, etc. up to a certain threshold that will grant them rights for immigrating. Yet, despite how celebrated diversity has since become, it isn’t reflected in the archives. That realization came in conjunction with finding an album of photos my dad took when he moved to Canada in 1973. This was in essence the representation that was missing from the official archives. He was engaged with student activism, organizing protests in front of parliament. He was an immigrant body who displayed political agency in the public sphere. All of these reflections about representation of self, community, and national identity came clashing together.

Bowen: I also quickly found myself working in very white archives as well. The narrative about Amber Valley, the black settlement in Northern Alberta my family belonged to, rested on the presumption that despite racial differences everyone got along. That this was a lie became more and more apparent as I dug into the archives, making notes of sociopolitical context of the time. Archival materials explicitly detailed antiblack hostility—threats of mob violence and lynch mobs, documented political interference, media smears about black savagery, inferiority, and so on. Over time, I have come to understand that the family myth of peaceful cohabitation was partially true, in that it reflected a practical negotiation for living in harsh climates. The life and death realities of homesteading and the extreme weather of the region made it necessary for my family (and the greater settlement community) to negotiate an uneasy civility between racist neighbors and government officials as a means of survival. In other words, the archive turned out to be a means to measure the accuracy of the constructed family myth versus reality. Yet, at the same time, navigating the white archive also demonstrated how data about my community was often lost, hidden, or buried. Overall, I got this sense that we were not valued because we were largely absent.

Deanna Bowen, still from The Promised Land, 2019. Original footage from Heritage, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 1962

Courtesy the artist

Hoàng Nguyễn: I’m still trying to make sense of the colonial relationship between photography and Indochina. I have this notebook where my great-grandfather has written about our family history from the 1700s and a collection of five-hundred photographs he gathered that range from the late 1910s to the end of the Vietnam War. While one has to keep in mind who has access to the camera—members of the upper middle class—this is a rare instance of the Indochinese documenting themselves during a period when colonial powers and then photojournalists produced the imagery of what Vietnam is.

Gabrielle Moser: I came from a much more traditional academic background, where I spent seven years studying photographic colonial archives. My interest in bringing this group of artists together came from this experience, thinking about what to do with images in state hands that for the most part go unseen by the larger public. The archive I looked at for my dissertation included seven-thousand images, but only two thousand of them had been seen by a wider audience at the time. Wondering about how to engage with these ethically and responsibly, I began looking at how artists handle archives. The artists gathered here work with a variety of collections in very different ways, but each think about how they can develop narratives about history, identity, sovereignty, and belonging that run counter to the official ones.

Jacqueline Hóang Nguyễn, Untitled, 2018, from the series Presence in Absentia. Sand. Installation at Gallery 44, Toronto. Photograph by Darren Rigo

Courtesy the artist and Gallery 44, Toronto

Butet-Roch: Speaking about strategy, Jacqueline and Deanna, you’ve both employed a wide array of methods to manipulate archival materials. For instance, Jacqueline, you’ve facilitated sessions where you invited peers to scan and caption pictures from family albums for The Making of an Archive project, as well as transformed photographs taken from the collection of relatives. Similarly, Deanna, you’ve worked with moving and still images, as well as textual sources, and in turn reenacted, re-staged, or re-interpreted them. How do you determine which is the best way to make the usually unseen teachings of these documents come to life?

Bowen: While some of it hinges on aesthetics, I constantly strive to analyze how the state has shaped how our story has been told. Re-enacting and re-staging events comes from a desire to have a bodily understanding of what was going on at the time. Often the only way to really understand the weight of a moment and its representation is to re-stage it, record it, and then publicly re-present it again. There are also photographic documents that I bring forward as living images because the emotions they speak to are better represented that way, like that of my mom and her siblings and cousins at a funeral. I felt a still moving image was the best way to present the active grief that my mom experiences.

At Gallery 44, I’m showing the full-length appropriated version of a thirty-minute narration of my family’s migration that was produced by the CBC in 1962. It involves family members singing gospel hymns that have been strung together to create that story. It has all the aesthetic values of 1960s black-and-white television. It reads like a variety show. It’s heavily romanticized. It’s fundamentally inaccurate. But it’s important to bring forward because it’s the best kind of example of how the reality of our black experience in Canada has been erased to make space for a blackness that’s been produced and disseminated by the state.

Hoàng Nguyễn: I’m presenting a new piece, which stems from the time I spent at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm. I found a photograph in their collection that is of someone who is also present in the album my great-grandfather put together. I was inquisitive about how this person came to be in these two very different spaces. What had been the photograph’s journey in one case and the other? While I knew who the person was, thanks to our family’s record, the museum didn’t have her name. It was titled “woman with a dragon dress,” when in fact, it was the portrait of the last empress of Indochina! In other words, this established collection that is highly praised, celebrates not the empress of Indochina, but the explorer who brought back the image from his field trip. Whereas ours, which is kept in one of those 1980s photo albums with the sticky pages and filled with handwritten captions, puts the emphasis on the person photographed, not the photographer. This contrast led me to think about the precariousness, the ephemerality of what my family holds, especially given that it could have been destroyed at any time during the wars and the journey to Canada. It made me think of the Buddhist mandalas, images that are printed in sand and exist only during the time of their making. I was able to develop a technique where I can reproduce images from my ancestor’s album in sand. They’ll exist for the time of the exhibition and then be brushed away. In this respect, they’ll hint at the ephemerality of the type of knowledge and histories that exists within families, especially that of people of color, of people of the diaspora.

Deanna Bowen, still from The Promised Land, 2019. Original footage from Heritage, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 1962

Courtesy the artist

Butet-Roch: Your respective works hinges on access to a wealth of materials that could have disappeared for multiple reasons, some related to resources and sociopolitical circumstances, others to state motives or even its brazen ignorance. How has that aspect been reflected in how you approach, handle, and disseminate these pieces?

Bowen: I have a formidable, radical, rebellious ally who used to be an archivist at the CBC and who understands the importance of bringing the fraught narratives embedded in their footage to light. I’m not seeking permission in disseminating this pirated version of the piece. It’s not lost on me how ironic it is that I need to have a white gatekeeper to access the archive of my own family’s history. Beyond that, we need to have a discussion about how a publicly funded corporation is making top-down decisions about what will be de-accessed. They don’t see the value of what has been considered B-roll footage. But there’s so much to be learned from what the CBC produced as “color” for in-between segments on the news or other programming. I’ve been pushing up against the CBC for many projects now. I’m very consciously staging work that puts them in the hot spot.

Hoàng Nguyễn: I want to echo your experience with the CBC. When I was at their archives in Toronto, I had made a selection of moving images for my film 1967: A People Kind of Place (2011), as part of the research and exhibition project Space Fiction & the Archives, and their archivist, looking at my selection, questioned the validity of my work as well as my credentials for handling these images. At one point, he mentioned that if it were more recent materials he would have asked for my drafts to make sure that it abided by the values of the CBC! That is highly problematic, especially from a publicly-funded broadcasting company. How can they demand that their values be embraced and reproduced by all other cultural producers using their materials?

Butet-Roch: As you mention this inability to recognize the significance of materials within the archives, I think of a word that Gabrielle used to describe the works you’ve been making, which is “affective,” as it relates to emotions. Is considering what an image stirs in you—as opposed to what it shows you—a way to expand our understandings of what these images tell?

Moser: That’s my hope, with the exhibition, at least. To do resistant work in the archive, in my experience, is to not look at the caption, or the organizing logic, or the hierarchies that the archives are telling you to pay attention to, but to stay with the distracting details and the emotional texture of the images.

Hoàng Nguyễn: There’s also something to be said about the absolute rehearsed narrative of how one is supposed to approach the archive or to read an image; it crystallizes the narrative. The moment you start to poke around the footnotes or the annotations, you access a human aspect that opens up all the cracks and gaps that then enables you to see the person or the people you’ve been overlooking.

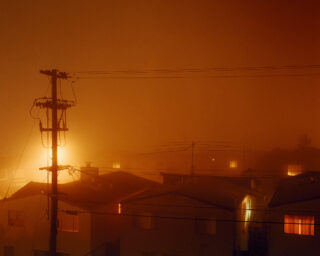

Hajra Waheed, PETRO SUBURB 3/3, 2019. Collage. Photograph by Paul Litherland

Courtesy the artist

Butet-Roch: And that, in turn, as Gabrielle mentions in her curator statement, brings up the idea that archives can serve as blueprints for a yet to be realized future. How so?

Moser: A lot of my thinking comes from Ann Laura Stoler, a colonial anthropologist who wrote a wonderful book called Along the Archival Grain (2009). I borrowed quite liberally from it, especially the title of one of the chapters, “Developing Historical Negatives,” as the title of this exhibition. In it, Stoler says that one of the things you find in state archives are plans for things that have not come to pass, either paranoid plans for a crisis that never arises or very fantastical hopeful ideas—and what is a hopeful idea for a colonial bureaucrat can of course be potentially very dangerous. She calls them blueprints or negatives in that a photographic negative might produce a positive, or it might remain undeveloped. I’ve been thinking about how that happens within state materials, but also in the resistant ways that vernacular or radical outsider collections imagine a different future.

Bowen: The Canadian state has done an exceptional job at erasing my community as far as the national narrative goes. There is no active black history in academic pedagogy. The ways in which you create a different future is to work with this deeply problematic, deeply one-sided archive and re-organize it in such a way that challenges how white archivists approach it. Questioning and rejecting the way it has traditionally been read has the potential to inscribe new meanings to existing archives and push forth a new vision.

Hoàng Nguyễn: The question of the blueprint resonates a lot with Mary Kelly’s text “On Fidelity: Art Politics, Passion and Event” (1990) where she talks about the political primal scene and why so many artists today are looking back at the past. For her, the primal scene is this psychoanalytic concept about the unspoken words, rules, and expectations of parents in relation to their kids. It’s not being mediated, but it’s being felt. You have this sense of what is right and what is not. She uses that concept and casts it within a larger political context by calling it the “political primal scene” whereby whole generations come to life in a given political context that shapes their understanding of what is acceptable and what isn’t. For me, the late 1970s and early ’80s was very much shaped by this promise of multiculturalism. But the fact that my family holds this unique collection of images, makes us the stewards of an alternative narrative, opening up for different ways for imagining the future by questioning what the unspoken expectations of the political context we entered were.

Moser: That idea, Jacqueline, is especially helpful in thinking about intergenerational knowledge transfer. There’s a big historical reach in the work presented. Yours spans decades. Krista Belle Stewart’s recording of her grandmother singing, which is also included in the exhibition, dates back to 1918. That’s one-hundred years of trauma, memories, and histories that’s on display. Automatically, it makes you think about what the next hundred will bring.

Developing Historical Negatives was on view at Gallery 44, Toronto from May 3 to June 1, 2019.