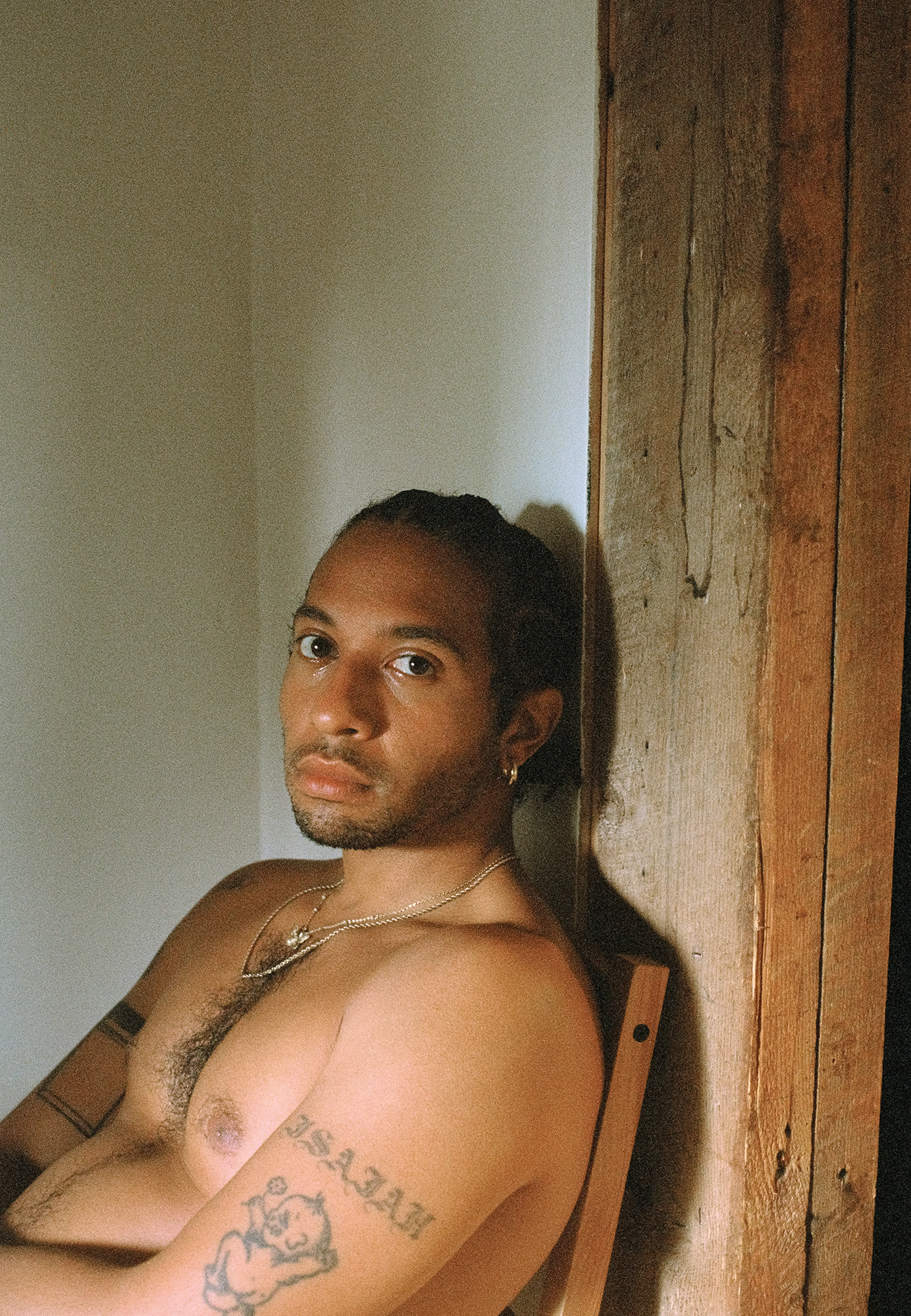

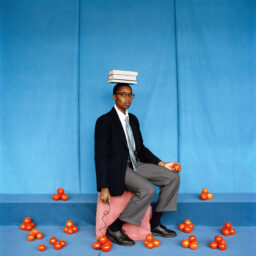

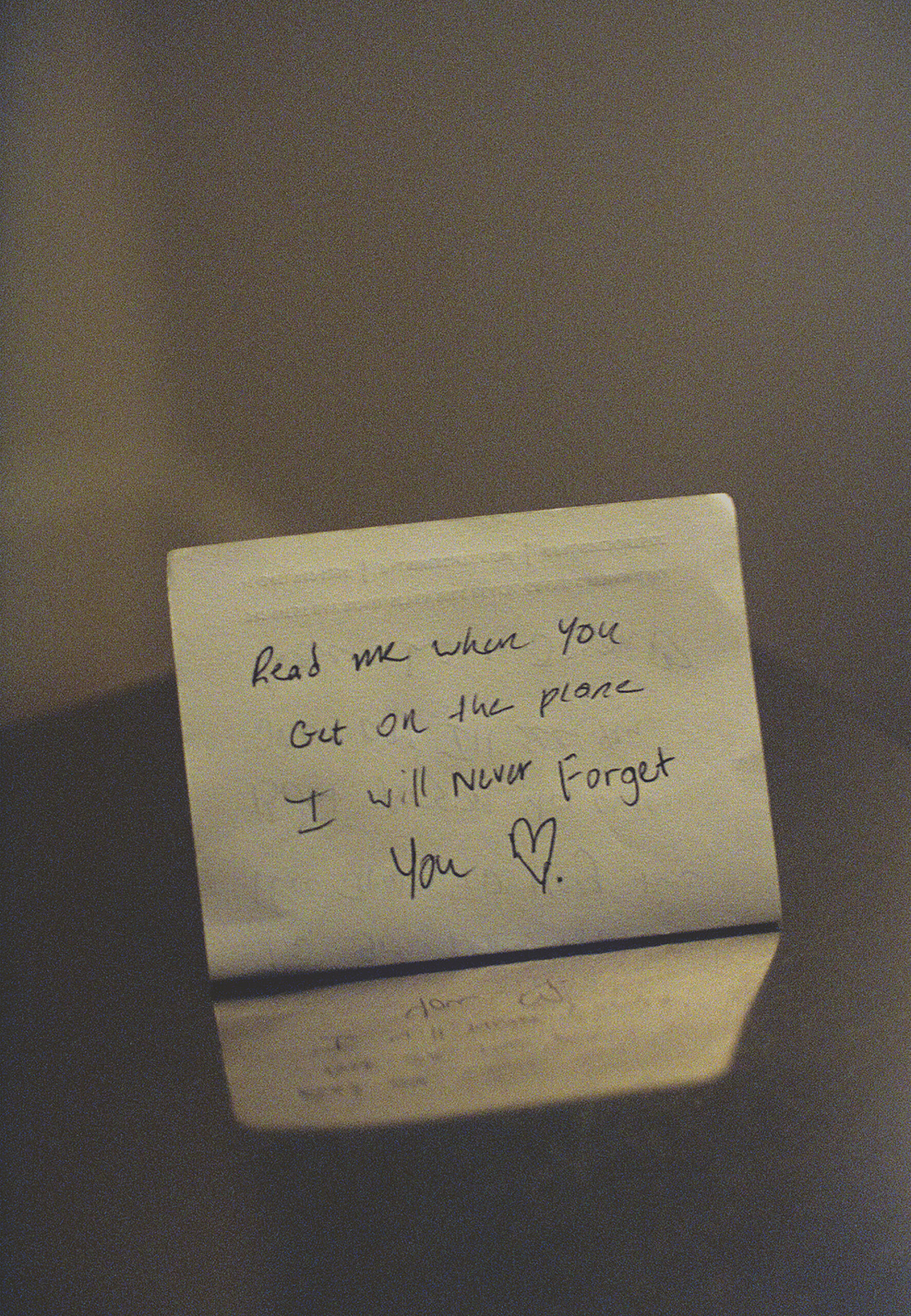

Clifford Prince King, remember this feeling, 2023

Clifford Prince King is a self-taught photographer and filmmaker known for his intimate, tender, and atmospheric images of Black queer men. He revels in the possibilities of leisure time, whether picturing care and comfort—or a latent erotic charge, the sense the chemistry is right for just about anything to happen. King’s work was featured in Aperture’s “Ballads” issue, published in the summer of 2020 and inspired by the legacy of Nan Goldin’s book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. His first book, Orange Grove (2020), was shortlisted for the 2023 Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards. “A lot of the imagery I try to create is just placing Black men in scenarios or scenes that seem familiar,” King told Aperture. “And so the ultimate goal to me is creating imagery where we see these Black men—whether they’re masculine-presenting or effeminate—and give that imagery a space.”

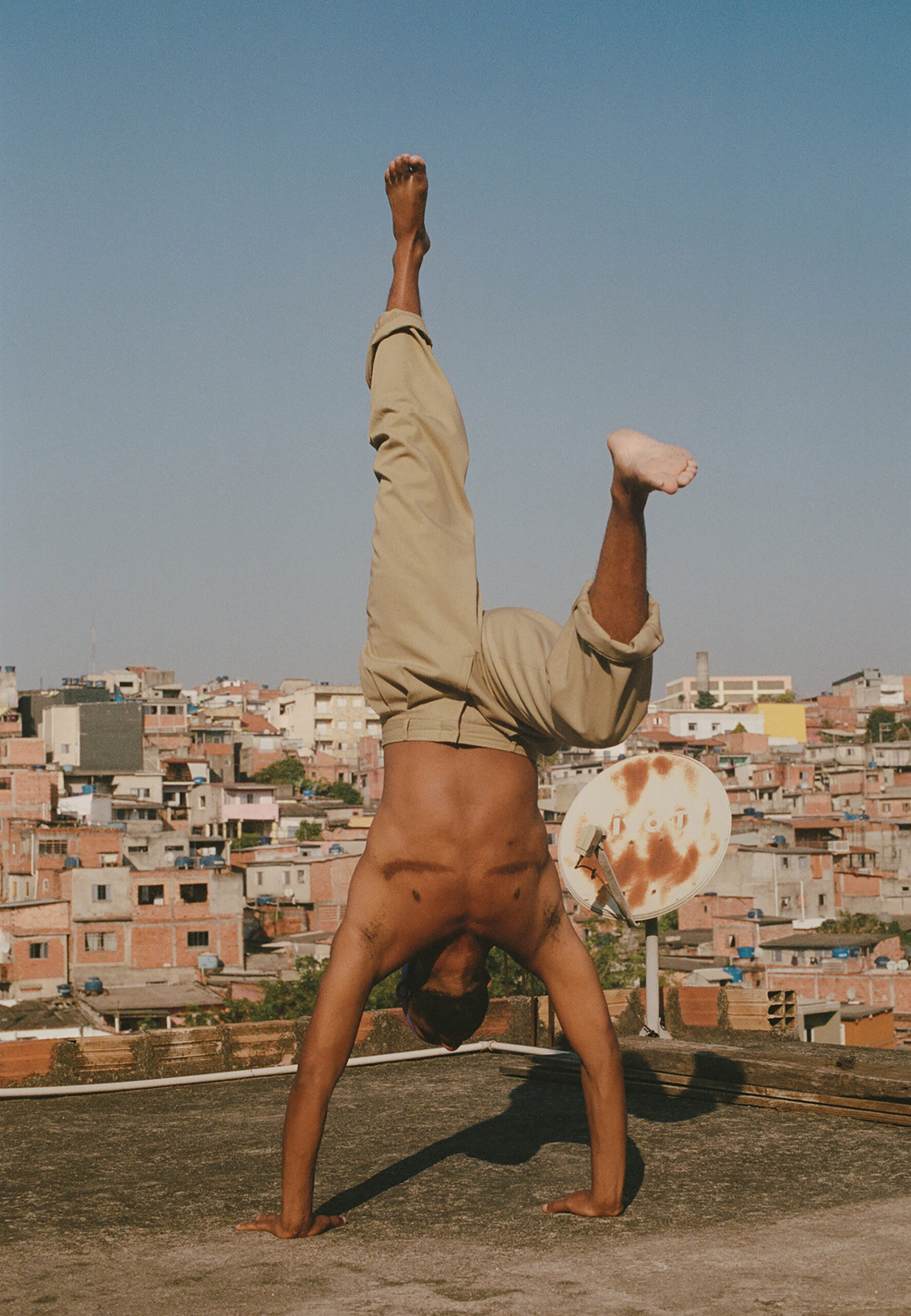

This season, King’s photographs are on view in an exhibition organized by the Public Art Fund and presented at JCDecaux bus shelters and newsstands on the streets of New York, Chicago, and Boston. Made in various locations, from Brazil to Fire Island, the photographs in Let me know when you get home expand upon King’s generous vision of love and friendship, and present a window onto the lives of young men kissing, lounging, and just being in the world. In February, on the occasion of the exhibition’s opening, King spoke with the artist Lyle Ashton Harris at the Cooper Union in New York about ideas of sexuality and belonging. Here is their conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Lyle Ashton Harris: I want to take a moment of silence to dedicate our conversation to the memory of Brent Sikkema, and to acknowledge his vision and the gifts he gave to so many of us. To start, I want to congratulate you and Public Art Fund on your exhibition of thirteen new works created in the past year.

Clifford Prince King: Most were created over the summer, at BOFFO Residency in Fire Island and the Eighth House residency in Vermont. Then I went to Brazil for two weeks—it wasn’t technically a residency—and then I went to Light Work in Syracuse, followed by the Cayman Islands.

Harris: I grew up in the Bronx, the northeast Bronx to be exact, and I negotiate the city in varying ways. What came to mind is the level of intimacy between men in your work—two Black men, two queer men—in a public sphere, and what it meant to grow up as a Black queer in the Bronx even today, at my age and station. Maybe trauma is one way of looking at it, in terms of hypervigilance in negotiating location, space, et cetera. I am interested in how these images function as public art and their power to give agency to Black love, intimacy, and queer representation in a public space. I’m intrigued by that, the radicalness of that.

King: Yes, a lot of this work was made outdoors, but it was still private while outdoors. Seeing the photographs on display in the street now feels almost as though the behind-the-scenes is being displayed in the opposite kind of environment. Most of the work that I’ve done is a lot more interior-based, and I’ve observed that a lot of your work is as well. But even photographing people outside, there is a level of alertness of surroundings, in order to keep the people you’re shooting feeling comfortable. You don’t want people saying things while passing by. You just want to provide a safe environment for creativity to flourish.

Courtesy the Public Art Fund

Harris: I think it’s going to be very beautiful to see how people from different walks of life engage with the work. I appreciate that, creating a safe space when you’re photographing. Part of the beauty here is that they will be exhibited at hundreds of sites across three cities, and we can consider what it means to have this imagery and experience in those places, which is a very powerful thing. I’m thinking of the Grand Fury campaign “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” in 1989, and what it meant at that time to critique stereotypes around HIV and AIDS, in terms of both its transmission and the power of public art, the power of using a public sphere to engage the complexities of intimacy.

Take us back to your early days in Tucson.

King: I didn’t have any sort of visual narrative of what my life could look like living in my authentic truth until I was much older. Thinking about growing up in Tucson, Arizona, not in an art household, most of my media exposure was the Disney Channel. I minimized myself a lot and stayed out of the way. I was a good kid and I just did normal things. I was on Tumblr a lot, just building a creative archive of things that I would find interesting, and I watched a lot of movies during the summer. My first love is cinematography, and that’s how I picked up a camera, by way of the moving image.

Harris: When did you get your first camera, and who were your subjects?

King: It was very competitive to get into photography class in my high school—and I didn’t get in. But someone who was in the program gave me an old Canon when the cameras were being thrown away due to the program ending. During my sophomore year of high school, I just started taking photos with it. Tucson was landscape, cactus, family. Eventually, I took a class in Portland intermittently for six months, but it was mostly just my friends or myself if I went out of town, and street photography.

There’s an early photo I took of a washing machine on top of a car, just random things that I found interesting. I used to get the film processed at Walgreens before I found a small camera shop in Portland. Toward the end of my time there, I started to develop a mission more clearly: I wanted to make friends that were Black and queer in the community, and I used my camera as a way to get to know people. This was at a time when Instagram was kind of coming up more and people wanted to book shoots and have content, around 2015. I would offer portrait or event photography, and I would also take my own photos, so it was kind of like a trade.

Harris: Where were you meeting people?

King: Mostly when I went out, on the street, or dating apps. And there was a small ballroom scene in Portland. How have you met the people you’ve photographed?

Harris: Well, firstly I was influenced by my grandfather, who shot thousands of images documenting his friends, family, and the church. Also my cousin Ricky, who made the invitation card for my first show in New York and photographed our whole family in black and white, as well as my stepfather, who taught by example. There was always the presence of a camera around, the ritual of taking pictures of each other. It came naturally, and I also observed the way my grandfather would choreograph things. It was a running joke among his three daughters that he took a lot of time to compose a photograph. You know what I’m saying?

King: It’s a personality trait. My dad had a VHS camcorder, and he would narrate home-improvement projects. Looking back on the film, he’s talking to himself about what he’s going to do to our kitchen, and then I started doing that with my room reorganization. I would paint it and do all these things that I thought were really interesting at the time, and film it. Then I would also mix music videos in, so there were breaks between my interior-design quests. Things like that kept me busy: making a playlist, learning about my taste. There’s something very special about time with yourself.

Harris: I love that. Looking at your work, there’s such an architecture of intimacy. Let’s talk a little bit about some of the subjects in the photographs.

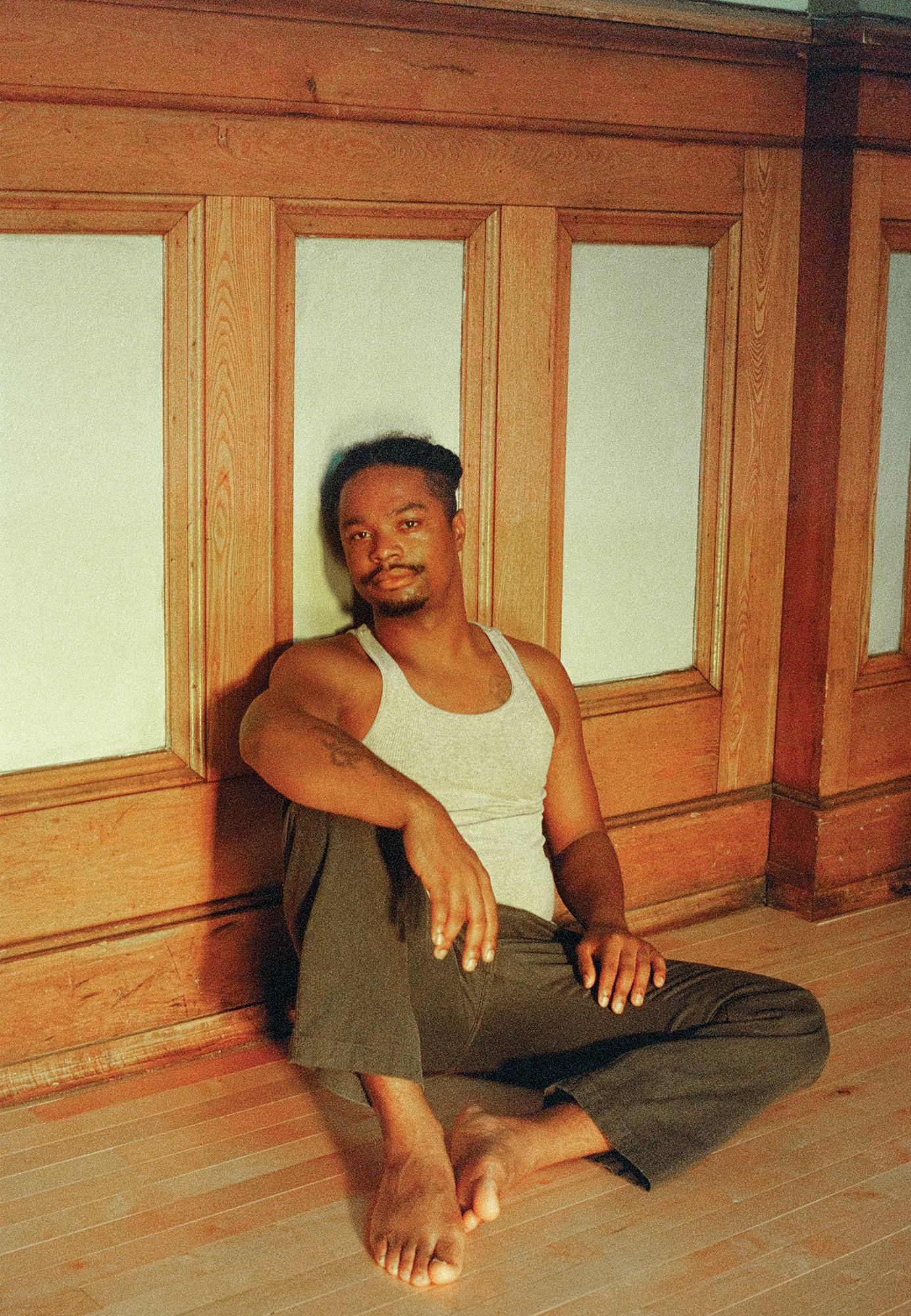

King: I think they’re all friends. Going to smaller towns, I really want to connect with local people in a way that isn’t taking from the city. Oftentimes I’ll photograph in my quarters, where I’m staying, versus going out and taking photos of people in their neighborhoods. I’m not opposed to it, but careful about that. I met one subject on an app and we had coffee, then met for a meal a few days later. I was going over the idea of taking his photo because at Light Work, there’s a huge auditorium lit by this fantastic orange light. It used to be an elementary school and is now an apartment building. I remember trying to figure out what time of day the light was best, and I told him to come over at 6:30, that certain special window when the light hit, and then we took photos including morning glory.

It was very specific. When it comes to elements of time and daylight, it can be a little stressful, but if things are happening, I just surrender the technical aspects, whether the light is gone or if it’s going to be blurry. There are certain images that I’m very particular about what I want to get at, but if not, then that’s fine too. At least I tried, or if it didn’t work out, it was for a reason and the end result is what was meant to be . . . I’ve shot some people and there was no film in the camera. But then two months later I’m like, thank God, because that person ended up being not someone that I wanted to photograph. And I’m just like, look at that. You know what I mean? I kind of trust for things to happen.

Harris: Yeah, I’ve done that.

King: Do you still talk to the subjects of your photos?

Harris: Yes, in most cases, for better or for worse, I would say that I’ve had a longstanding connection with many former lovers, partners, or dear friends. I’m very much inspired by your generation, too, and by your work, in terms of my trajectory. I appreciate that it relates to me revisiting certain early moments, but also the moment of today, in my late fifties, actually recapturing the erotic charge in works I’m thinking about, which pertains to my practice overall. For me, it’s about a certain intimacy and exchange.

King: There’s something that’s built. It’s trust, it’s understanding and communication.

I think even the photos that don’t specifically feature two men, there is a layered, underlying feeling of intimacy. It can be universal, but also, if you know, then you know.

Harris: I’m allowed to come into the space and answer the call of the great Marlon Riggs, in terms of Black men loving Black men as a revolutionary act. I feel, in a way, that there’s something about the energy of the work, which feels that you are involved in creating skin or language around that erotic possibility that’s also a political possibility. I reflect upon the way that Riggs came out at the landmark Black Popular Culture conference, and what it meant at that time to claim space in such an environment, and similarly, the way your portrait of two men on the cover of your book Orange Grove (2022) engage in a level of frottage before Martin Luther King. There’s a tension and notion that one can engage with, without having to be hit over the head with a hammer. You were saying, “I can draw from a multiplicity of identities and histories, et cetera,” and that feels fresh.

King: I feel that things just take different forms. There’s always the need to be an advocate for something, but the way that happens changes forms and is regenerated throughout different times. I really try to surround myself with people who inspire me, so then the work is not to be credited entirely to me, but to those people who surround me and their existence that enlightens me. It’s a collaboration between people, creating that space that you find to be beautiful and then waiting for moments to happen within that space. You just have to be present and pay attention to watch it unfold.

Courtesy the Public Art Fund

Courtesy the Public Art Fund

Harris: I understand and I appreciate that. I’m also interested in your Public Art Fund project’s inevitable afterlife, how these billboards are functioning within the community, and the reaction to them. How do you document that, because there’s the work, but there’s also how that work engages with the public. In a culture that is deeply homophobic and racist, I’m wondering how to give a space in which to document the impact of these images, thinking of the recurring incidents of violence against and vilification of trans and queer people. At fifty-nine, trauma still arises, recalling what it meant to negotiate, for example, being called a slew of derogatory names in junior high school many times a day. Part of your exhibition’s power is the visibility of these very intimate photographs in public space.

King: There are some people who will say, “These issues are no longer issues. It’s 2024, no one’s racist anymore.” But then when there are projects like this, a lot of things still continue to happen, and there’s no coverage on it. It’s sidelined almost, and I feel we have a continuous fight for ourselves.

Harris: I’m intrigued by how your photographs resonate in the global context, because you are a global citizen, as demonstrated by the varying locations where you shot this imagery.

King: Right, and I think even the photos that don’t specifically feature two men, there is a layered, underlying feeling of intimacy. It can be universal, but also, if you know, then you know.

Harris: Tell us more about the works in Let me know when you get home.

King: Two of the featured works are set at Eighth House in Vermont, where I rested for two weeks and let my body catch up with my emotions.

Harris: What does resting look like to you?

King: I watch a lot of bad TV, or I’m doing nothing, being outside, off my phone. Just kind of dissociating a little bit, if I can. How about you, living upstate?

Harris: Resting, to me, means eating well, feeding people, going for a walk every day, a little yoga and music.

All photographs courtesy the artist; STARS Gallery, Los Angeles; and Gordon Robichaux, New York

King: Do you have a favorite photograph you’ve taken?

Harris: There’s one, a childhood friend of mine named Gasper. It was taken in ’85, and his image has appeared and reappeared over the years throughout my work. In May, my work will be the subject of an exhibition at the Queens Museum that is anchored by my Shadow Works series, which are unique assemblages that layer various imagery. This photograph of Gasper appears in several of these works. There’s something in this photograph that contains the impression this person left on me. In the photograph, he’s glancing at an athletic training guidebook with ankle weights at his feet, as he sits in front of a makeshift backdrop, smoking. So clearly, I was thinking about constructing images in my childhood bedroom. I’m wondering out of the thousands of photographs I’ve taken, why that one? Maybe because there was innocence and the erotic possibility that was never consummated in the most literal sense, but it was an exchange. It was an engagement. And only very recently as my exhibition catalog was going to print, did I find out whether Gasper was still living or not. A studio assistant helped me find that he’s a CEO, with two kids in Westchester. We spoke on the phone about a month ago.

King: That’s beautiful.

Harris: What I really love about the work is that there is a certain freedom that I feel, and it’s generative for me today as someone who, even when I was an undergrad or in grad school, had to figure out what it meant to somehow carve and open up a space to be dealing with these issues here, in those spaces. It has necessitated a certain criticality, and I feel inspired by your work, the synergy, and the connection that offers new possibilities.

King: Well, all of this is through people in photography before me. It’s kind of like I’m doing that because of y’all, so thank you.

Clifford Prince King: Let me know when you get home is on view in New York, Chicago, and Boston through May 26, 2024.