The Dark Landscapes of Don McCullin

In this interview from the Summer 2009 issue of Aperture magazine, Don McCullin speaks about his experience documenting war and conflict in Biafra, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Cyprus, Lebanon, Northern Ireland, and Vietnam, among other places, with Fred Ritchin, now dean of the School at the International Center of Photography. As Ritchin writes in his introduction, “McCullin rebels against the moniker ‘war photographer.’ He is not content with the impact of his decades’ worth of images, particularly their insufficient role in diminishing the very violence they depict.”

Coinciding with the release of Aperture’s Don McCullin, a chronological survey first published in 2001, now expanded on the occasion of McCullin’s eightieth birthday, we reprint an excerpt from their conversation. This excerpt also appears in Issue 17 of the Aperture Photography App.

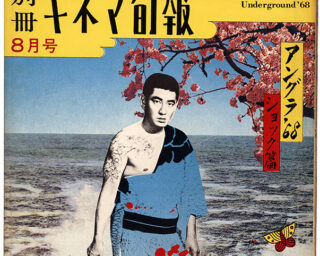

The battlefields of the Somme, France, 2000, All images © Don McCullin

Fred Ritchin: Today we’re going to talk about you being a photographer, a larger career than that of a war photographer.

Don McCullin: I’d like to get away from the awful reputation of being a war photographer. I think, in a way, it’s parallel to calling me a kind of abattoir worker, somebody who works with the dead, or an undertaker or something. I’m none of those things. I went to war to photograph it in a compassionate way, and I came to the conclusion that it was a filthy, vile business. War—it was tragic, and it was awful, and I was witness to murder and terrible cruelty. So do I need a title for that? The answer is no, I don’t. I hate being called a war photographer. It’s almost an insult.

I wasn’t trying to pick up the Robert Capa mantle; I went to war because I felt I was suited to do it. I was young and ambitious, but the ambition started to fade away when I saw people coming toward me carrying dead children, or wounded people coming toward me holding their entrails . . . things like that. Things the average man in the street simply wouldn’t understand, because he’s never been there, thank God.

FR: In the work you’re doing now, the Roman work and the landscapes, it’s as if life has more to offer than simply death. Your sense of time is different. You’re working much more slowly. The time passes over thousands of years. These are traces of things. Before, it was quick, instantaneous, news.

DM: It was like what we would call a head-butt. It was about butting somebody in the head and showing them my images. Now I’m behaving in a much more dignified way. Naturally, I’m getting older and coming to the end of my life, so I’ve slowed down. I’ve reinvented myself. The reason I am doing these new landscapes, this new Roman project, is because it’s a form of healing. I’m kind of healing myself. I don’t have those bad dreams. But you can never run away from what you’ve seen. I have a house full of negatives of all those hideous moments in my life in the past.

So now my challenge is the landscape, the archaeological landscape of Rome . . . it’s very challenging and it’s very beautiful. When I can get into the pariah nations—Syria and Lebanon, they’ve eased up a bit, though Syria is a notorious police state—but when I’m there, I am totally safe and alone. I am constantly pushing the barriers, simply for the privilege of getting my cameras out and taking beautiful photographs.

FR: Of stuff that happened two thousand years ago.

DM: Yes. Because it’s not as if I’m trying to photograph today’s political struggles. In a way, I am trying to do justice to the culture of these historical sites.

FR: But it seems to me you’re also trying to find a meaning in life, what’s good in life or what’s important, or as you say, dignified. The war itself is the abattoir. War itself is the meaninglessness of life, and somehow that is there, even in your landscapes and the Roman work. You’re finding something else, something spiritual, some other kinds of answers in life.

DM: My landscapes are dark. People say: “Your landscapes are almost bordering on warscapes.” I’m still trying to escape the darkness that’s inside me. There’s a lot of darkness in me. I can be quite jovial and jokey and things like that, but when it comes down to the serious business of humanity, I cannot squander other people’s lives.

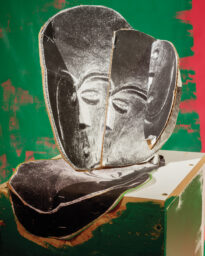

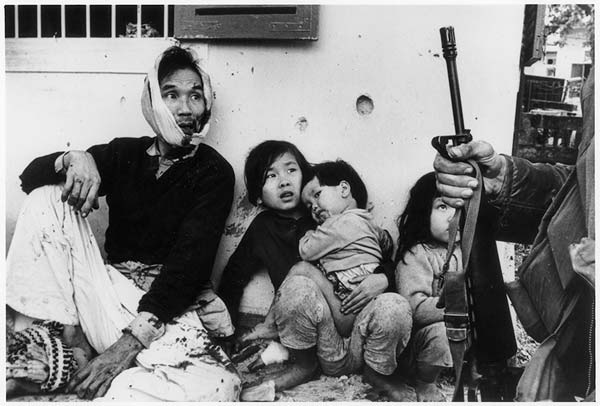

Vietnamese family after a grenade-attack on their bunker, Hue, 1968

FR: Is that because of what you’ve seen in life, or because of where you’ve come from in life? Are you talking about your life as a war photographer, or are you talking about the neighborhood where you grew up—a sense of fairness of play?

DM: Well, there wasn’t any of that where I grew up. The boys I grew up with were determined to become criminals. I never really wanted to be incarcerated in prison. I spent a few days in prisons in Uganda, and got beaten by the soldiers. Freedom was paramount to my dreams.

And in England we have this class structure. It’s very much there—though it’s being exchanged for new racial structures and religious structures that have come in. England is quite a racial country: it was never really on your side if you didn’t have white skin. So I grew up with all those things, and I’m still living with them, even though I live in the countryside. There are many hurdles in my country; you’re never really going to be free of the hurdles.

FR: But in a way, then, maybe you’ve turned to a kind of poetry of the image, or a kind of lyrical photography, with tonal ranges that are different, more studious, larger formats. . . . In other words, you talk about it as informational, the “Roman Empire,” but you’re doing something else. You’re showing the light and the beauty, the metaphors. You’re working in a broader way. It’s like you have a bigger palette now.

DM: Yes, it is a bigger palette. The Roman Empire as it was, was extraordinary, apart from the fact that it was based on cruelty and horror. . . . You know, when I’m in these great Roman cities, which earthquakes and time have destroyed, I like the fact that I am there, I am enjoying the challenge—but all the time I feel as if I can hear the screams of pain of the people who built these cities. It doesn’t go away. The Roman slaves were paid nothing. All they probably expected was a bowl of food. So when you’re in these remarkable cities, you’re not comfortable really.

You could say: “Well, why are you doing this?” I’m doing it because I have never collectively seen several Roman cities in the Middle East. What I’m getting at is that when I first started as a photographer, I thought: “This is going to be good. I’ll get behind this camera and I won’t have to worry about academia. I’ll just take pictures. It will be easy. And of course, there’s no politics involved!” I’ve done nothing but political assignments in my life. Even going back to ancient Rome, it was steeped in politics and evil.

I feel comfortable doing landscapes in England. I don’t have any apologies, I don’t have problems. And I never do landscapes in England when it’s sunny. I always do them in the winter when the trees are naked. It’s more Wagnerian. I don’t know . . . I like drama and I like darkness.

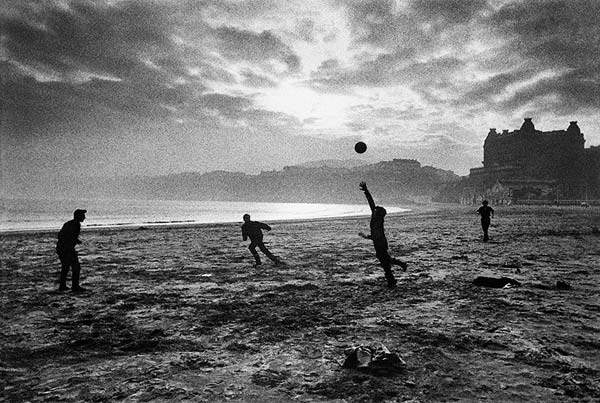

Fishermen playing during their lunch break, Scarborough, Yorkshire, 1967

FR: Eugene Smith used to listen to Wagner when he was printing. That’s how he’d stay up for nights in a row, listening to Wagner, and he’d get those deep prints, like yours—deep skies, your dark skies.

DM: Well, I was influenced by Eugene Smith, as much as I was by Bill Brandt. I like the great prints that Steichen made. I really studied photography in depth. [I brought a stack of books] home to where I lived, in a Hampstead Garden suburb, and they were as tall as this table—and my God, they were full of information.

I used to sit nightly when my children went to bed, studying those books. They became my university. I taught myself everything in photography that I know. Don’t get me wrong about this, I still take a stand—but I am still a student of photography. The moment I think that I have arrived, I’ve had it. I am never going to arrive.

Don McCullin will appear in conversation with Sebastian Junger at the 92nd Street Y in New York on October 30: click here to learn more.

Click here to read the complete interview from Aperture magazine on the Aperture Digital Archive, free through November 6.