Art and Activism in a Contested Democracy

In spring 2017, Sarah Lewis, guest editor of Aperture magazine’s “Vision & Justice” issue, led a series of classes at the Brooklyn Public Library on the relationship between photography, citizenship, and the law. Here are five reflections from participating students.

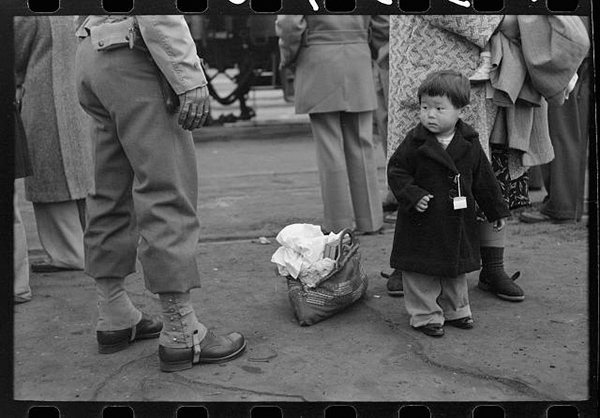

Courtesy the Library of Congress

Taiyo Na

To make the removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II more palatable to the public, the federal government used euphemistic terms such as “evacuation,” “assembly,” and “relocation centers.” It was in this context that Russell Lee’s 1942 photograph bore the following caption: “Japanese-American evacuation from West Coast areas under U.S. Army war emergency order. Japanese-American child who will go with his parents to Owens Valley.” It’s a deflective description, but the image itself offers the viewer far more tragedy, injustice, and pathos.

In this photograph, a Japanese American child with a face in disarray stands next to a soldier. The image presents a relationship, a binary and a hierarchy. An overstuffed bag, perhaps the mother’s and “only what we could carry,” occupies the space between the child and the soldier. Between them, there is also a chasm of citizenship, race, and exclusion: the child will board the train in the background to reside in a federal prison in the middle of a desert, and the soldier will enforce that removal. Korematsu v. United States, the 1944 Supreme Court decision, validated the internment of Japanese Americans for the reasons of “emergency and peril.” Under the guise of an “evacuation” and perceived threats to national security, who are the children “tagged” and forcibly removed today? A process of classification always precedes state-sanctioned exclusion. When the waiting is too long and the “tag” unwarranted, its impacts are life and death, and a democracy unfulfilled.

Taiyo Na (Taiyo Ebato) is an educator, writer, and musician based in Brooklyn.

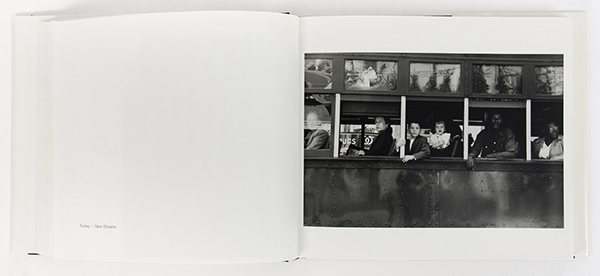

Aperture Foundation Library

Jonathan Michael Square

In 1955, one year after the passing of Brown v. Board of Education, Robert Frank photographed a streetcar in New Orleans. The Supreme Court had declared separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional, a death knell to legalized racial segregation. Starting in 1955, Frank traveled across the U.S. taking the photographs that would later be collected in The Americans (1958). Despite the optimistic zeitgeist of the Eisenhower era, Frank showed the racial and socioeconomic hierarchies that still divides us.

New Orleans, where Frank photographed the streetcar, also figures into a pivotal Supreme Court decision, Plessy v. Ferguson. In 1892, Homer Plessy, a creole man of color, bought a first-class ticket, and boarded a “whites only” car. He was arrested and charged with violating Louisiana’s Separate Car Act of 1890. The case reached the Supreme Court, where segregation was upheld. When Frank took this photo in the middle of the next century, public transportation in New Orleans was still separated by race.

In this photograph, the viewer must confront the gaze of Frank’s subjects, both black and white. There are many photographs of “whites only” signs segregated South from this era. But social stratification does not have to be marked or articulated. Inequality had become so inscribed in the American psyche and the national visual grammar that it could be enforced and internalized without explicit instruction. It would not be until the activism of Rosa Parks later that year, and the passing of Boynton v. Virginia in 1960, that buses and trolleys across the nation would gradually be desegregated.

Jonathan Michael Square is a writer and historian who currently teaches at Harvard University, where his work explores the intersection of fashion and slavery in the African Diaspora.

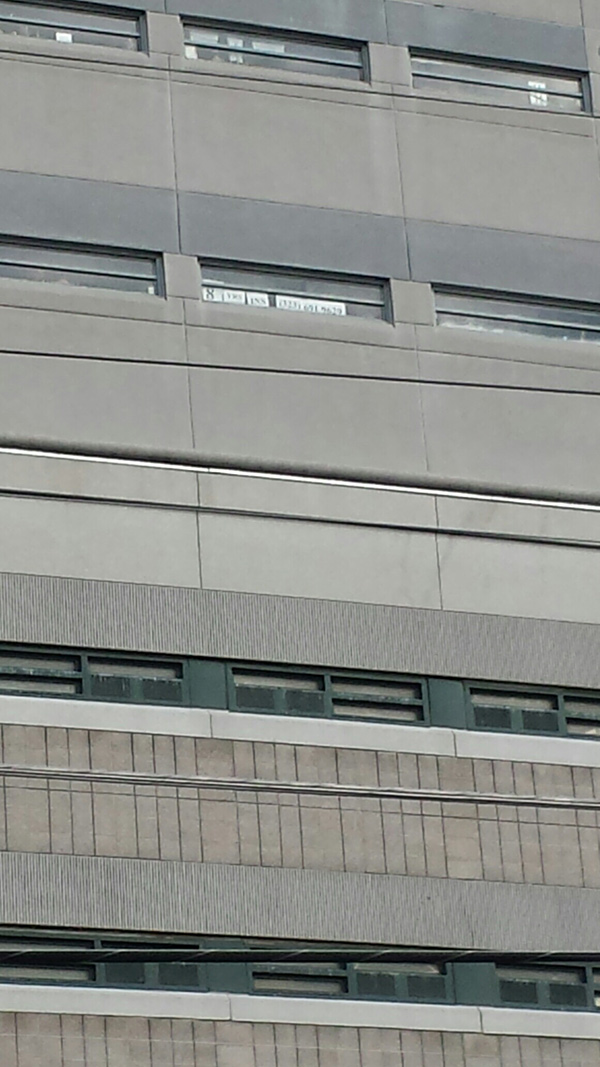

Courtesy the author

Carmen Hermo

The blankness of the architecture in endless thrust in this photograph, neither light, landscape, nor horizon, indicates the intimidating size of the Etowah County Detention Center, a building managed by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Gadsden, Alabama. The gray concrete slabs, disrupted by abstract apertures, slowly become legible as windows. A pixelated zoom reveals a series of paper-sized printouts that read “8 YRS INN,” followed by a phone number. Someone has squeezed this plea for attention into the compressed window panes, and it is tragically duplicated by the other papers posted in the windows one story above legibility. Made to share the detainee’s phone number with the ACLU during a Shut Down Etowah campaign, this photograph represents the invisibility of immigrants detained in the United States. The image, taken by the ACLU of Alabama’s Public Advocacy Director, Lucia Hermo, has not been widely circulated, and the efforts of activists—hunger strikers on the inside, organizers on the outside—have gone largely unnoticed by the general public.

Etowah houses undocumented immigrants ensnared at entry to the U.S., as well as long-term green card holders and asylum seekers who committed petty crimes. Detainees endure poor medical services, meager or rotten rations, and a structure designed to limit fresh air, sunlight, and outdoor recreation. These cruelties are compounded by the length of stay, determined by an unregulated, obfuscated process, which the ACLU argues violates due process. Jennings v. Rodriguez, currently under review by the U.S. Supreme Court, will determine whether indefinite detainment in inhumane conditions is permissible for non-U.S. citizens. Without visibility for these displaced peoples, their many years inside will continue to go unnoticed.

Carmen Hermo is Assistant Curator for the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum.

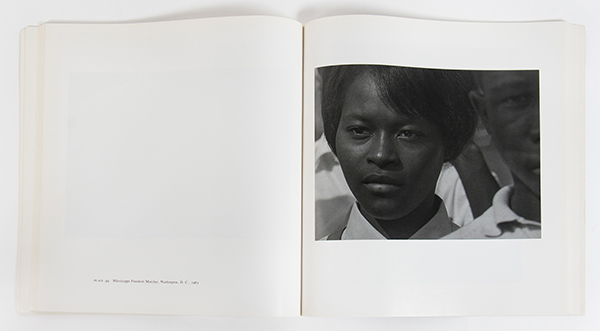

Aperture Foundation Library

Nina Crews

When Roy DeCarava traveled to Washington, D.C. for the March on Washington in 1963, he did so with “some trepidation.” Images of people marching and holding signs seemed, to his mind, to be “too pat, too obvious.” DeCarava is best known for his photographs of Harlem. Though most of his images were created in public spaces, his work is instantly recognizable for its stillness and intimacy. He created deeply personal photographs through careful composition and softly modulated tones.

Mississippi freedom marcher, Washington, D.C. (1963) is a portrait of a young woman. The details of her eyes, hair, nose, and mouth are crisp. A shadow cups the right side of her face. She is solemn, breathtaking. She doesn’t seem to be aware that she is being photographed. But this is not simply a picture of a demonstrator.

The woman is standing in a crowd. There is a young man in the foreground, his face bisected and blurry, and behind her, a stray, dark arm contrasts with the marchers’ white shirts. The young man looks directly at the photographer. Did DeCarava see him when clicking the shutter? Or when he reviewed contact sheets of the many images he took that day? Perhaps this watchful presence only revealed itself in the darkroom under orange safety lights as the print processed in the developer tray. The man’s gaze breaks the fourth wall, making the viewer a participant. “Who are you?” he seems to ask. Or, perhaps, “I see you watching us.” As we gaze upon the young woman prepared to fight for what is right, this young man’s presence reminds us that this fight is ongoing, and compels us to consider our relationship to the movement today.

Nina Crews is a children’s book author and illustrator whose next book, Seeing Into Tomorrow, celebrates the haiku of Richard Wright and will be published spring 2018.

Courtesy the Associated Press

Valentine Umansky

In a photograph from 1962, two young girls, one white, one black, stare at a sign planted on the front lawn of a suburban home, their backs to the photographer. The sign reads: “NEGROES! This community could become another GHETTO. You owe it to YOUR ‘FAMILY’ TO BUY in another COMMUNITY.” Housing promoters had foreseen the postwar building boom, which would require mass-produced housing, and purchased large swaths of land on Long Island. As the Federal Housing Administration offered financial backing to non-mixed developments only, some—including the Levitt brothers—openly favored racially segregated housing. To this day, Lakeview, the neighborhood in which this photograph was taken, remains a symbol of racial segregation. And, as we speak, African Americans have a one-in-two chance of facing housing discrimination within their lifetime.

Yet, legal protection exists. The landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co (1968) concerned Lee Jones, a black man from St. Louis, who was not allowed to purchase a home because of his race. In 1968, Jones brought the case to the court under the Civil Rights Act, which bars both private and state-backed discrimination. The court sided with Jones and, reversing many precedents, held that the 13th Amendment authorized Congress to prohibit private acts of discrimination because of “the incidents of slavery.” In 1962, this picture acted as a precedent but, today, it reads as a warning: for the President who, in the late 1960s, at the beginning of his career in real estate, was sued by the Justice Department because he would not rent to African Americans. The image is also a reminder that urban ghettos have been used as an institutional arrangement ensuring the ongoing subordination of African Americans in today’s United States of America.

Valentine Umansky is a Curatorial Intern at the Photography Department of MoMA. She is the author of Duane Michals, Storyteller, published by Filigranes Editions in 2015.

Read more from Aperture, Issue 223, “Vision & Justice.”