Dispatches: Jason Fulford on San Francisco

Jason Fulford, San Francisco, 2012 © Jason Fulford

It’s been a year now since I drove from Scranton, Pennsylvania, to San Francisco and let the air out of the tires. My wife was given a yearlong fellowship here to work for an idealistic nonprofit that creates new technology for city governments. I tagged along, excited to wander the same streets as Henry Wessel. We arrived in October—still summer in San Francisco—to a warm reception. Frish Brandt from the Fraenkel Gallery, Joseph del Pesco from the Kadist Art Foundation, and Chris McCall from Pier 24 introduced themselves as the welcoming committee.

On week two, I received an invitation from Richard Misrach to join a photo-study group. He was starting a new incarnation of an old idea, and explained it like this: “Since the 1970s I have held ‘salons’ … I reach out to a handful of local artists, we generally meet at my studio, or rotate to the other studios, everyone contributes to a potluck meal, we look at work, share readings, and sometimes create collective projects. There’s no set agenda—it evolves democratically. It’s an old-school model, for sure, but I highly recommend it.” The group focuses on one topic each meeting— ethical problems related to shooting documentary portraits, for example—and discusses it from different angles. There is sometimes friction, and often follow-up over email. It’s a sort of spirited continuing-ed class that ends up resonating in the background between meetings.

Misrach’s salon is one small slice of a large photography scene here. In the past twelve months, I’ve made my way from dinner table to dinner table on both sides of San Francisco Bay. I’ve found that there are three generations of local photographers that feel connected, like an extended family.

One figure who is brought up at nearly every dinner is Larry Sultan, whose work tended to comment on community and family. Larry passed away three years ago, but his presence is still felt. On top of his career as a photographer, he was known for his generosity as a teacher. I asked artist Dru Donovan, who worked at his studio for a time, what made Larry so special. “He mixed wisdom with doubt,” she said, “and critical intellect with vulnerability and honesty.” Dru also told me that Sultan insisted on regular “study halls” during the workday: “For about a half hour or so, he and I would drop everything work-related and pick up something to read. Study hall was founded because life is rich, full, and for the making and participating in.”

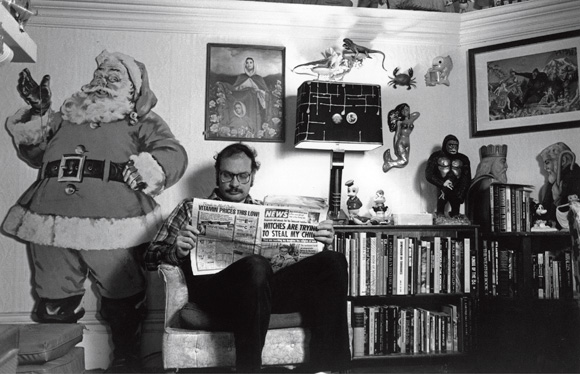

Communities here are shaped by those who are missing as well as by those who are present. Another important influence, who died last year, was the filmmaker George Kuchar. George inspired his students as much as Larry did, though using very different teaching methods. A professor at the San Francisco Art Institute, he threw his students into the chaotic productions of his own insane films. Artist and curator Jordan Stein fondly recalls Kuchar’s “AC/DC Psychotronic Teleplays” class, during which he was cast in a movie with a script that was “basically one enormously unsavory food pun.”

George Kuchar, 1960’s. Photographer unknown. Photofest.

Sultan and Kuchar both fostered a real sense of community as teachers and mentors. If you attend any of the lectures sponsored by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Pier 24, you’re likely to run into some of the working photographers in town. Many of them also teach at SFAI and at the California College of the Arts.

Jim Goldberg studied under Sultan decades ago, and now teaches at CCA. His studio is located above one of the cavernous Mission Street thrift stores (where I imagine Kuchar’s students hunted for props). Talented photographers pass through, and often end up working for Jim: Lindsey White and Eric William Carroll are two who have put in time at the Goldberg studio, and are now making smart and thoughtful work.

The photographic output in the San Francisco community varies wildly—analog, cameraless darkroom experiments; traditional social documentary; conceptual installationbased work; and giant homemade cameras. More than any unifying sensibility or aesthetic, there is a strong network of support between photographers. And—maybe this is a California thing—the support is heavy on positivity, light on criticism.

The diversity of styles is seen in the number of artist-run photobook presses in the Bay Area. Each has its own sensibility and reaches out to a different audience. Paul Schiek publishes TBW Books from an overgrown industrial pier in Oakland. He hires local printers to produce his Subscription series, which features a mix of local photographers (Abner Nolan, Todd Hido, Katy Grannan) and out-of-towners (Mark Steinmetz, Elaine Stocki, Alec Soth). Paul generally gives artists free reign, within a set of restrictions—page count and trim size. Nick Haymes, a recent transplant via London and New York, is publishing a mix of international work under his imprint, Little Big Man. Many of his books bring to light decades-old pictures from photographers’ archives—Surf Riot by Nick Waplington documents a 1986 beach riot; To the Past by Nobuyoshi Araki is a sort of photographic diary going back to 1979; and Kitajima Keizo’s 1991 USSR is a collection of pictures that has been aging in storage like whiskey. On the lighter side, Ray Potes, a.k.a. Hamburger Eyes, pumps out black-and white ’zines and “mega-zines” (more than one hundred) with energy and humor, filled with work from a collective of local photographers.

Nick Waplington, Surf Riot, 1986 © Nick Waplington, courtesy Little Big Man

Regionalism seems to be on the rise in the United States, and I think the trend may have started in San Francisco. Many of the restaurants have long supported local farms. Composting is mandatory. Tech companies open up workshops and lectures to the public (including their competitors). A friend described the local cuisine this way, and I think it’s an astute metaphor for photography: yes, it’s about the way it looks and tastes, but it’s more about the way it makes you feel, once it’s inside your body.

Jason Fulford is a photographer and cofounder of the nonprofit J&L Books. He is a contributing editor to Blind Spot magazine and a frequent lecturer at universities.