John Divola's Upside Down Formalism

John Divola, Untitled 90UJ, 1990

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

The titles of the two series by John Divola currently on view at Gallery Luisotti in Los Angeles could hardly be starker: the Five Prints Portfolio (1987), outdone for emptiness by Untitled (1990). These titles outline the bare minimum of photographic formalism—flat, rectangular prints—which his work then attempts to pry apart. Each of the five vertical photographs in Untitled has a vellum-smooth surface, mottled with abstract whites and grays. On closer inspection, the pictures show the brushed-on unevenness common in “alternative process” photographs, as if the chemistry had been slopped on by hand. Ditto the uneven top edge of three of the five images, which resemble mesas on a horizon. In fact, the subject of the photographs turns out to be a backdrop smudged with flour; what seems to be ragged tiers are actually brush strokes along the curled edge of the paper, held to white panels with pushpins. Divola introduces a confusion between additive and subtractive, positive and negative; it’s a “process” photograph, after all—if not quite an “alternative” one. The series offers a two-dimensional subject, a grisaille abstraction—the texture of a ridged, dripping black surface bearing its own dust-thin layer of gray marks—that then peels into depth.

John Divola, Untitled 90UC (detail), 1990

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

Divola, born in Los Angeles, is known for photographs that document his vandalism-style interventions in abandoned buildings and other interstitial spaces with a wry eye towards painting’s collapse into photography. In the mid-1990s, he made a series titled As Far as I Could Get, comprising vertical landscape shots of a lone, distant, running figure with his back to the lens. Divola set the camera’s timer, then sprinted down its field of view. No matter how much distance Divola puts between himself and the film plane, the image always snaps flat. The grayscale images in Untitled, are also remnants of a weird performance. The clouds of grayish white that drift across the compositions, formless and out of focus, are also the main formal element of each: fogging the black ground, puffing up the scene into space-time. The suspension of this dust cloud places Divola’s series (like many of his others) within the space of an action. The flour hangs like a kind of fleeting sculpture, a distribution of matter in midair—and thus points to the gesture that put it there. How strange, artificial, and temporary is art, Divola seems to say. His dry titles take on a gallows humor.

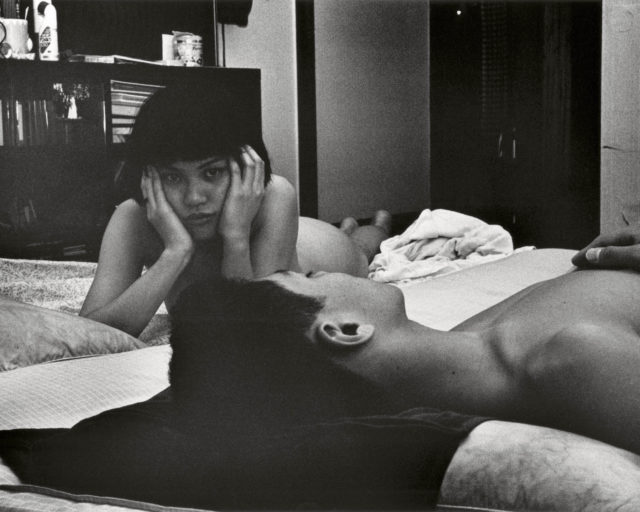

John Divola, Flying/Falling, 1984

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

In the Five Prints Portfolio, with brilliant dye-print color, Divola emphasizes “prints” and their icy flatness. Near the center of each square frame, hemmed in by the foliage of a forest or backyard, are pale, paper-like objects saturated by colored light. A cutout of a howling wolf—Wolf (1983)—is lit with red, and the strip of sky at the frame’s top—an echo of Untitled—burns orange. In Flying/Falling (1984) a human silhouette plummets toward a smoky pink patch of depressed reeds—or else they’re blown upwards, as if by a strong wind or a small explosion, by the pink strobe’s pop. This indeterminacy between flat and round, dead and alive, is the core vertigo of the photograph. In Cyclone (1984) a little cone, blasted with magenta light, stands upright in a spot of bare ground in the woods. The light source is visible: a flash, wrapped with a gel, hanging from the tip of a c-stand, which is not so different from the bare branches around it. Red light fills a branch, canting across the top right corner of the frame, as well as some of the leaves in the middle ground. But it’s a sunlit sky that punches cyan through the background. We’re in the woods, but not too deep.

John Divola: Physical Evidence is on view at Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles, through September 9, 2017.