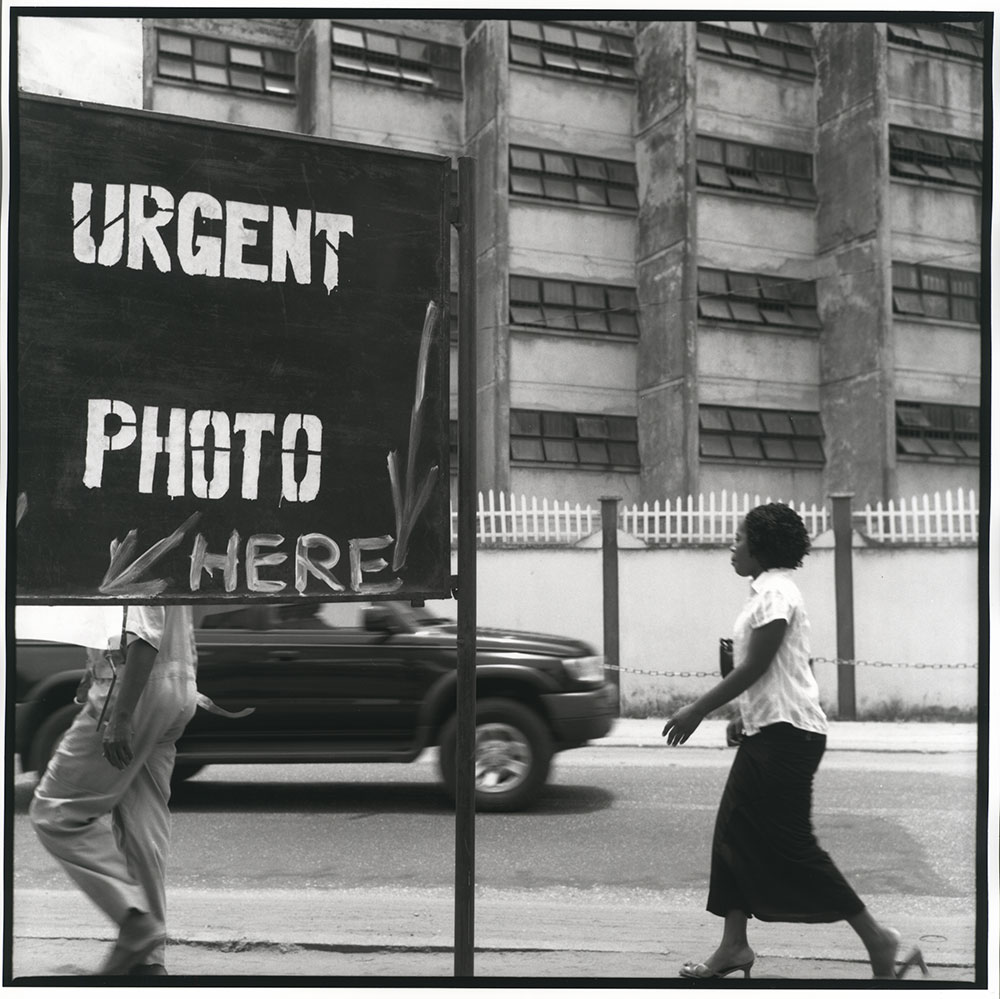

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Victoria Island, Lagos, 2006

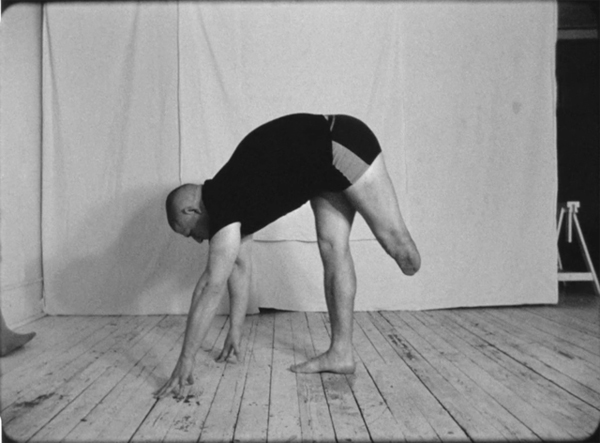

Some of the most provocative images in the latest edition of the quinquennial exhibition Documenta, first presented this spring and summer in Athens, show a man kneeling on top of a table with a hoop and a stick in his hands. He wears a moustache, has scars on his face, and his torso is bare. In a series of twelve black-and-white photographs, which until last month were all squished into a tight spot on an upper floor of EMST, the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, he strikes various poses animated by anger, bemusement, and agony. The figure in the photographs could be an avant-garde artist—male, of course—experimenting with modes of conceptual performance and minimalist sculpture in the makeshift lofts and factory spaces of downtown New York in the early 1970s. In fact, he is the revolutionary anthropologist Franz Boas, mentor of everyone from Margaret Mead to Claude Lévi-Strauss, and famed for the ethical foundations he laid for the field. Though still underappreciated, Boas was also crucial for his tireless disputations against eugenics and other bogus theories of racial superiority, which, in the first half of the twentieth century, bent scientific findings to fascist doctrines.

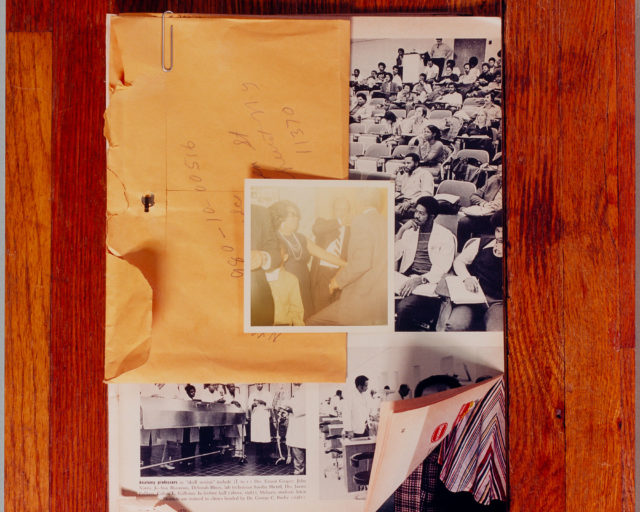

Photographer unknown. Courtesy the National Anthropological Archives, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

The Boas photographs date back to the turn of the twentieth century; the photographer is unknown. The images were taken as studies for a sculptor who was helping Boas to build a diorama for what is now the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., part of the Smithsonian Institution. The diorama—one of the fabled “life group” displays for which the anthropologist became known—was meant to represent the Hamatsa, a dance performed by initiated members of the Kwakwaka’wakw tribes of northwestern Canada. Set on the threshold of the human and spirit worlds, the dance demanded performers to emerge from the “mouth” of a supernatural, cannibal creature. (Because expectations are perhaps higher at Documenta than anywhere else, a colleague who admired the inclusion of the Boas photographs quipped, to the side, “I mean, they could have shown the diorama, too. That would have been amazing.”)

© and courtesy Loock Galerie, Berlin

Throughout his career, Boas returned again and again to the notion that indigenous peoples, as the subjects of ethnographic study, had much to teach the anthropologists who all too often depicted them as primitive. According to the writer Claudia Roth Pierpont, who profiled Boas in The New Yorker in 2004, “he demolished the standard claim that Indian and Eskimo speakers used different sounds for the same word at different times, and showed that the purported vagueness of ‘primitive’ speech was actually a characteristic of the primitive ears of anthropologists, who transcribed different approximations of what they heard at different times.” In the context of Documenta—organized by Adam Szymczyk with a team of some two dozen curators and staged, in Kassel, where the event was established in 1955, and, for the first time, in Athens, a city beleaguered by messy politics and financial strain—the Boas photographs carry many curatorial assertions and arguments, about art’s role in reckoning with colonialism, injustice, and conflict.

Courtesy the artist

The Boas photographs are also emblematic of an exhibition that draws on photography both for its record-keeping, archival function, and for its malleability. As a medium, photography is uniquely fit to capture the process of long term artistic pursuits, such as Hans Ejikelboom’s dizzyingly repetitive, typological photographs of street fashion from the 1970s until today, which double as a ruminative and sustained critique of global capitalism. Ejikelboom’s Photo Notes 1992–2017, on view in Kassel’s Stadtmuseum, brings direct, almost overwhelming evidence of his project into the exhibition space. But at Documenta, other such labor-intensive projects often, by necessity, happen far outside of the museums or galleries where people otherwise encounter them, learn about how they transpired, and consider what they mean, and so the work enters those places as small pieces of a much larger puzzle.

© the artist and courtesy Loock Galerie, Berlin

The archival function of photography in this Documenta is wonderfully represented in the pairing of archival material showcasing Maya Deren’s research on voodoo rituals in Haiti with a portrait of the voodoo painter Andre Pierre, whom Deren met in the 1940s. Photography as a record of long term projects finds expression in two expansive series by Moyra Davey and Akinbode Akinbiyi, which register, respectively, transmissions through the mail system and public space. A bit of both applications—the archive and the time-based study—comes through in Douglas Gordon’s intriguing film on Jonas Mekas, I Had Nowhere To Go (2016), which relies so heavily on the black space between barely moving images that it might well be a series of photographs.

Rathaus Kassel, March 3, 2017. Murat Çakır’s presence as a translator is required at the wedding of Çiğdem Yalcin and Göksel Akgül at Kassel City Hall because the groom, originating from Izmir in Turkey, doesn’t speak German. The young people met during the bride’s vacation in Turkey and decided to establish themselves at the center of her life. Mr. Akgül will work in Kassel at the bride’s father’s advertising agency. Mr. Çakır considers this photograph of the wedding ceremony important because the presence of the translator demonstrates that Germany is, and has been for long a time despite all political denial, a country of immigrants. The bride’s father is called Hüseyin Yalcin and belongs to the second generation of guest workers. The witnesses are Jessica Seitz and Senem Korkmaz

© and courtesy the artist

The works on view in Kassel’s Neue Gallery plot out a notably coherent argument and worked, for me, as the key to unlocking the meaning of this two-city, seventy-venue exhibition. Woven into the Neue Gallery display are Tina Modotti’s photographs of a radical Indian agronomist exiled to revolutionary Mexico who was experimenting with wheat production, and Sunil Janah’s photographs of the Bengal famine in 1945, a documentary project he undertook alongside Margaret Bourke-White. Extending a thread that runs throughout Documenta, these works explore the effects of hardship and hunger. In the Neue Neue Gallery, Kassel’s old Brutalist post office, two very different, but equally ambitious, photography projects occupy large spaces on the upper and lower floors. Upstairs, Ulrich Wüst’s black-and-white photographs of abandoned East German cityscapes before the fall of the Berlin Wall are classical and restrained, yet packed with drama and tension. Downstairs, Ahlam Shibli’s portraits of successive waves of immigrants to Kassel tell, in their extensive captions, a rich and complex history of assimilation, rejection, homesickness, and shocking violence.

Courtesy the artist

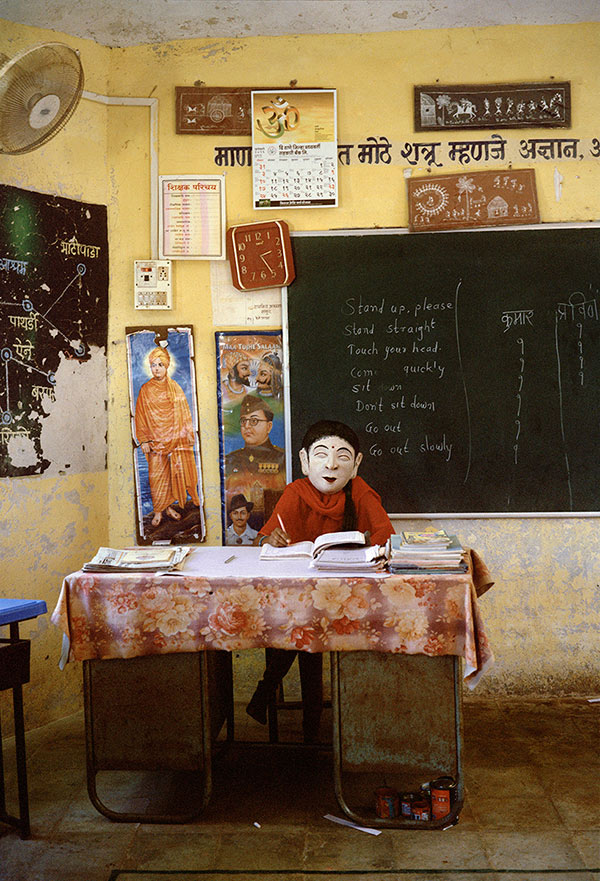

But photography as a tool of contemporary art shimmers in Gauri Gill’s Acts of Appearance (2015–ongoing), a series of lush, large-scale color portraits of the residents of a village in Maharashtra, which is known for making Adivasi masks. Instead of requesting the likenesses of gods and demons, however, Gill asked the residents—including the master mask-makers Subhas and Bhagavan Dharam Kadu, their families, and fellow volunteers—to make masks that portray their own lives. Then, she painstakingly orchestrated medium-format portraits of the makers wearing their masks in everyday settings. The resulting images unfurl narratives—vast commentaries on time, leisure, work, pleasure, hopes, dreams, fears, and futures—without uttering a word. Gill’s photographs occupy the same threshold between human and spirit as the Boas photographs enacting the Hamatsa dance, and depict the frozen moment of an elaborate performance to be a powerful—and politically consequential—thing indeed.

Courtesy the artist and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

Around the corner from Wüst’s photographs is a room filled with a six-screen video installation by the Polish artist Artur Żmijewski. His work is as galvanizing in Kassel as it was in Athens, where he showed the video Glimpse (2016–17), a silent, black-and-white excursion into the evacuated refugee camps of Calais, among others. The film walks a fine line between documentation and provocation, exposure and voyeurism: Żmijewski riffles through the belongings that people have left behind, daubs a black man’s face with white paint, and hands a broom to another man as if to put him to work. Żmijewski’s work in Kassel, Realism (2017), shows six men with amputated limbs, moving about their days, exercising, going to work, and returning home. The films, both silent, were shot on 16mm film and transferred to video; both toggle between moments of pathos, beauty, and pure repulsion. At times, Żmijewski nearly seems to push viewers away.

Courtesy the artist and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

Żmijewski’s films capture the essence of Documenta 14, and epitomize the role of photography—and, by extension, related styles of filmmaking—throughout the sprawling exhibition. Adam Szymczyk and his curatorial team appear relentlessly concerned with pulling together two modes of image making: the document of an action and the action as art. If the argument posed by the theme of this Documenta, “Learning from Athens,” is to urge us all to become political actors, Szymczyk’s treatment of photography seems to insist that images must occupy our social and political lives. Following the line of photographs from Athens to Kassel, art and politics are endlessly intertwined..

Documenta 14 was on view in Athens from April 8–July 16, and is on view in Kassel, Germany, from June 6–September 17, 2017.