The Inspiring, Contested Legacy of Dorothea Lange

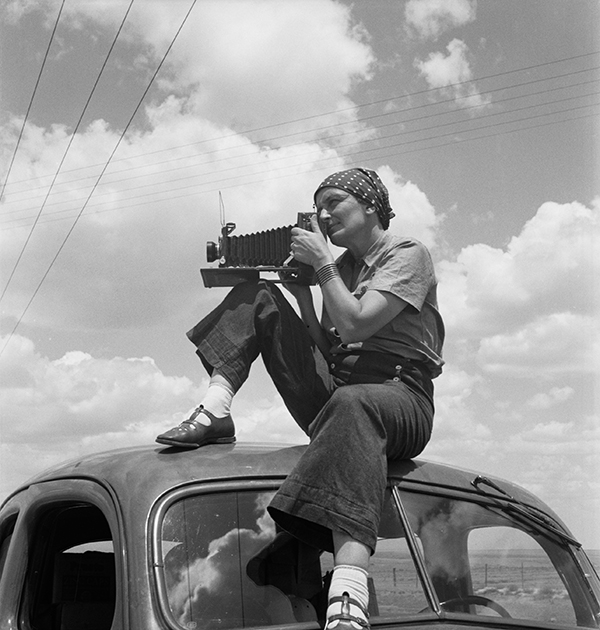

Paul S. Taylor, Dorothea Lange in Texas on the Plains, ca.1935

© The Oakland Museum of California

On May 13, 2017, the Oakland Museum of California opened Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, a major retrospective that surveys the photographer’s career through the lens of social activism. The exhibition draws on Lange’s vast personal archive, housed at the museum. Mixing a wealth of vintage prints with digital prints produced from archival negatives, the exhibition is supplemented with selections of Lange’s field notes, contact sheets, publication mock-ups, books, letters, and ephemera. Prints by three contemporary photographers influenced by Lange—Ken Light, Janet Delaney, and Jason Jaacks—round out the installation and remind visitors how powerfully she set the standard for engaged, empathetic documentary photography. A few weeks before the opening, I visited curator Drew Johnson to discuss the exhibition. The table was set for my arrival with the very first issue of Aperture—a reminder that the inaugural cover was a photograph by Lange.

Dorothea Lange, Shift Change 3:30 pm, Coming out of Yard 3, Kaiser Shipyards, 1942

© The Oakland Museum of California

Sarah M. Miller: Why is the Dorothea Lange archive housed at the Oakland Museum of California?

Drew Johnson: Last year was the fiftieth anniversary of the archive coming to the Oakland Museum. The museum was created in the mid-1960s to unite the existing collections of Oakland’s public history museum, natural history museum, and art gallery. It opened in 1969. Founding curator of photography, Therese Thau Heyman, brought the collection here before the museum even opened, in 1966. Therese approached Lange and Paul Taylor and there were a couple things that appealed to them about the museum. One, it was a local institution. Construction was about to begin, plans were being drawn up. It had been identified as the Museum of California and as a people’s museum. Last, Therese made it a big point that the Lange archive would be made accessible to the general public as well as to scholars and researchers, and that we would make prints from the negatives.

Dorothea Lange, Shipyard Worker, Richmond California, ca. 1943

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: Aside from the fiftieth anniversary of the acquisition, what do you hope to achieve with a Lange retrospective?

Johnson: Dorothea Lange has a permanent space in the gallery, but it’s been more than twenty years since we presented an extensive exhibition. Lange has always been relevant to current events. In the oral history interviews that Lange conducted with Linda Reese, Lange says she had seen recent images of migrant workers in the Central Valley, California in the 1960s and, if she didn’t know when they were taken, she would have thought they were from 1935. Nothing had really changed. One of the contemporary photographers included in the exhibition is Ken Light, who photographs Central Valley migrant farmworkers. If the subject wasn’t wearing a 50 Cent sweatshirt, it could still be 1935. And it’s not just about working conditions: Lange saw her mission during the Depression as understanding a refugee crisis in America, and generating empathy for refugees, which is also an issue of great relevance today.

The Lange archive at the Oakland Museum, as opposed to the collections in the Library of Congress and the National Archives, represents her entire career, from 1918 until her death in 1965. Twenty-five-thousand negatives. We spent a long time thinking about how to whittle down this huge archive, and that’s when we decided on the theme of photographer as social activist, and using photography to persuade. Lange is the prime example. Every documentary photographer I meet tells me how Lange inspired them, both in her technique and the issues she documented.

Dorothea Lange, Untitled (Oklahoma Mother in California), 1937

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: How is the exhibition organized?

Johnson: There is an introductory section where visitors look at her early life. She had polio and her father abandoned the family—a possible connections to her great capacity for empathy. Then Lange’s documentary photography is divided into three sections: The Great Depression, World War II at Home (the Richmond Shipyards series, and the evacuation and internment of Japanese Americans), and, last, postwar California which includes her least-known work.

Miller: People rarely discuss Lange’s work from the 1950s and beyond.

Johnson: She had a series of health challenges in the 1950s, but she also did these amazing projects that rarely see the light of day. She was fascinated by what she called the “New California,” this vast spread of suburbia and development. Death of a Valley (1956) with Pirkle Jones, which was about the removal of a community to build Lake Berryessa, presaged modern environmental photography. But she was interested in the development of the inner city, too. She explored it through street photography, as well as the Public Defenders (1957) series, shot right across the street at the Alameda County courthouse. That’s fantastic work, some of her best.

Dorothea Lange, Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California, 1942

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: Did you discover anything new in the process of planning this exhibition?

Johnson: I did uncover new information about Lange’s photographs of the wartime evacuation of Japanese Americans. The museum’s archive contains some of the best-known images, like the Japanese Owned Grocery Store and Japanese Children with Tags (both 1942), because Lange was working on her own before being hired by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). Most of that series was kept by the National Archives, but we also have a few examples from WRA negative envelopes that Lange seems to have borrowed and never returned.

From this body of work, I dug into the series of Japanese Americans being evacuated from their homes: they’re sitting on their porches with stacks of luggage, waiting to be loaded onto buses. I realized Lange was shooting houses on the site of what is now the Oakland Museum. In fact, some of them were shot from the window of the Alameda County Law Library right across the street. Those Japanese American families were living right here, at 12th and Oak.

Dorothea Lange, Oakland, California, 1942

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: The Oakland Museum’s exhibitions always have a strong education component. What will the points of engagement be? Are you planning interactive or educational activities in the galleries?

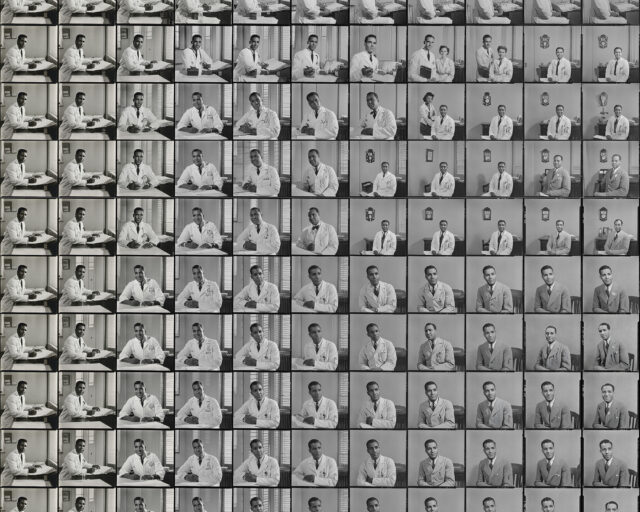

Johnson: There are two interactive activities. First, visitors will see examples throughout the exhibition of how Lange cropped a negative to increase its power. There will be sample images and movable frames so that visitors themselves can experiment with cropping Lange’s photographs. Especially late in her career, she would take the same negative and crop it three or four different ways. For Public Defender, there would be a portrait from the waist up, and then a version where she would zero in on the eyes, for example. For the other activity, there is a large magnetic bulletin board where visitors can sequence photographs with quotations, statements, and headlines—the way she did. There is a quote on the wall: “I used to think in terms of single photographs. No more.” Both in her home and her studio she had big bulletin boards, where she would group photographs and text in different ways until the sum was greater than the parts.

Dorothea Lange, Young Man at Manzanar Relocation Center, 1942

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: That’s an indication of how far Lange scholarship has come. In the ’80s and ’90s, Lange was a target of revisionist scholarship on documentary photography that treated cropping and sequencing like a crime—as though documentary forbade the shaping of information, and as though it were a coup to discover the means by which she editorialized. It’s nice to see her process resurface as a point of engagement, rather than a line of attack.

Johnson: Context and communication were crucial. She was frustrated when her photographs were shown in art museums, put on a wall without context—those images and words from interviews that she went to great pains to take down so precisely. Our thesis is that, through these techniques, she could make the picture more or less emotionally powerful. She could slant the meaning or emphasis in a certain direction. We are not putting a judgment value on that, other than by saying it illustrates her empathy, her desire to effect change, and her emphasis on the photograph’s use over its aesthetics.

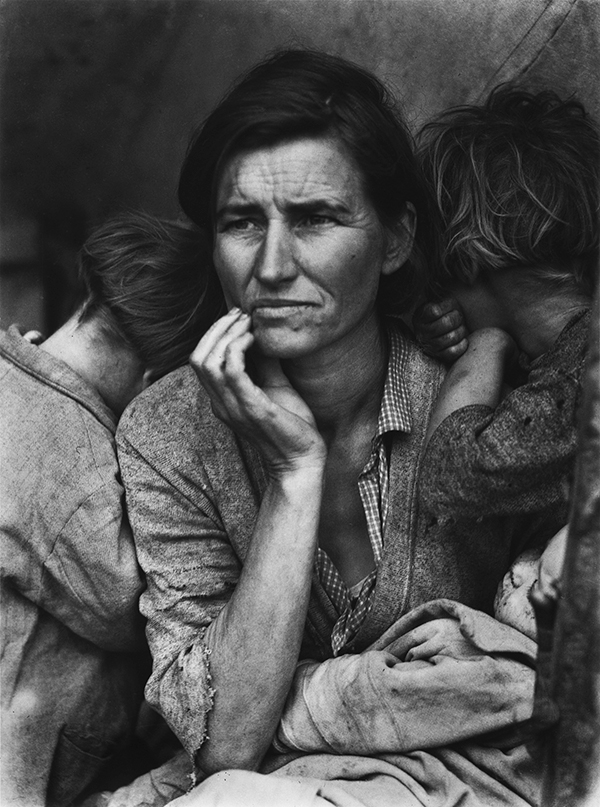

For that reason, we’re actually going to look at how Migrant Mother (1936), her best-known photograph, became de-contextualized over time—and why that is atypical for Lange. How do individuals become icons? Visitors walk past the six preliminary photographs from that day and then come across Migrant Mother in its own niche, Mona Lisa style. After that, there is a case filled with Migrant Mother tchotchkes and memorabilia including t-shirts and mugs. There are also examples of how the image was adapted to later messages, like the Black Panther newspaper, where the mother is rendered as a black woman. On the wall, quotes from various people, times, and contexts form a montage. Roy Stryker says, “You can see anything you want to in her. She is immortal.” Florence Thompson laments, “I didn’t get anything out of it. I wish she hadn’t taken my picture.” Lange says, “I do not remember how I explained my presence … I did not ask her name or history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two.”

Normally, Lange prized collaboration, as shown throughout the exhibition. She would talk with someone for fifteen minutes before taking her camera out. She would talk about their kids, talk about her kids. She let the children put their dirty fingers on the lens. It was important that her subjects knew why she was there and what she was trying to accomplish. Lange resisted making icons out of people, and yet this image inadvertently did that and caused distress for Florence and her family.

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, Nipomo, 1936

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: It makes sense to address the icon question head on. The way Lange usually interacted with her subjects is often lost in the controversy over Migrant Mother, but the controversy is unavoidable. The photograph has become a flashpoint for cynicism about documentary more broadly—for equating documentary photography with the exploitation of strangers and their suffering.

Johnson: On the other hand, for many people, the image continues to be deeply moving.

In general, Lange does not appear to have been an ideologue. She simply acknowledged problems that needed to be addressed, and said: I have a way to contribute. That said, Lange had convictions that drove her to defy the mandates of her employers, which we show. The WRA didn’t want her version of America to be seen—meaning the racism driving the Japanese evacuation order and the injustice of internment. And before that, the FSA told her not to address issues of racial discrimination in the South. One of the critiques from the ’80s, when documentary photography was under new scrutiny from scholars, was, “Why didn’t she shoot any people of color?” Excuse me?!

Dorothea Lange, Crossroads General Store, ca. 1938

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: Will the exhibition be a corrective to that assumption?

Johnson: I hope so. We point out that the FSA specifically instructed her to concentrate on white migrants, according to the theory that doing so would produce more widespread support. But she wasn’t going to have any of that. Her husband, Paul Taylor, was a labor economist at University of California, Berkeley, specializing in agricultural labor. He studied Mexican farm workers for years. When Lange traveled across the South, she was fascinated by it. She shot from across the white side of segregated lunch counter to the black side. And she was attuned to the legacies of slavery and racism in southern agriculture. In the exhibition we juxtapose Ex-Slave with a long memory (1938) with Plantation Overseer and his Field Hands, Mississippi Delta (1936).

Dorothea Lange, Ex-Slave with a long memory, 1938

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: Tell me about the contemporary work in the show.

Johnson: We have chosen three photographers because of the issues they’re interested in, and because they all have connections to Lange. Ken Light’s Valley of Shadows and Dreams (2012) is about twenty-first century migrant farm workers. He is a journalism professor at Berkeley who was inspired by Lange as a young photographer. He has also been running the Dorothea Lange Fellowship at the University of California as a juror, as have I, for the past twenty years.

Janet Delaney is a former Dorothea Lange Fellowship juror and winner. Her work South of Market, San Francisco, Then and Now (1978–86 and 2011–present) is about gentrification, and connects to Lange’s investigation of the “New California.” Jason Jaacks is also a former fellowship winner. He documents the Tohono O’Odham Nation along the U.S.–Mexico border, including how the border wall both affects and divides the community. He also focuses on recently deported Mexican migrants in the area.

Dorothea Lange, The Road West, New Mexico, 1938

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: It must have been hard to choose just three?

Johnson: The main idea of the show—photography as activism—is liberating because it allows us see the enormity of Lange’s legacy, but also to zero in on particular ways it has been enacted. For Lange, it was about seeing injustice and getting others to see injustice. All three artists demonstrate that idea powerfully, and each speaks about the influence and inspiration Lange provided.

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing is on view at Oakland Museum of California through August 13, 2017.