Across a Racial Divide, Images of Daily Life under Apartheid

An innovative book juxtaposes images from the archives of two South African families—one black, and one white.

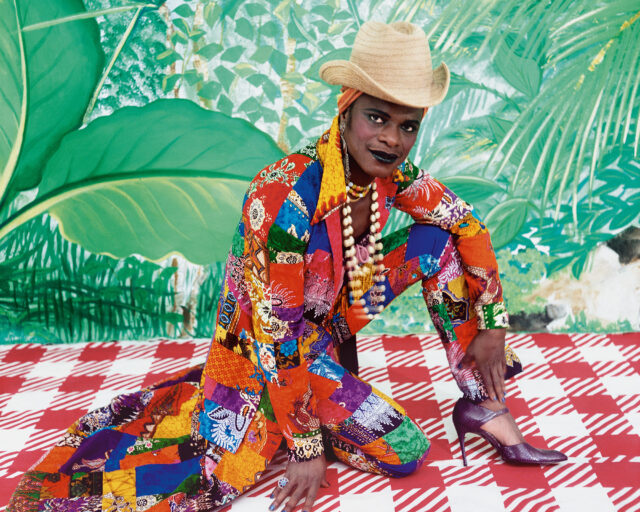

Unidentified subject, South Africa, ca. 1950s

Courtesy the Ronald Ngilima collection

Printed on tightly bound cloth, a curtain of soft ripples and floral design is rendered on the entirety of the book’s surface. A faint light emanates from the bottom left corner, infusing the texture with warmth and inviting us into Commonplace, an intimate view into the everyday lives of South Africans over the course of the twentieth century.

Authored collaboratively by Tamsyn Adams and Sophie Feyder, the book features photographs from two private collections—each informed by the movement and settling of communities within particular spaces in South Africa’s physical and social landscape: The Ngilima collection includes the combined work of two black South African photographers, Ronald Majongwa Ngilima and his son Thorence, who photographed life in the African, colored, and Indian neighborhoods in Benoni, east of Johannesburg, during the 1950s and ’60s. The other, the Drummond-Fyvie collection, dates back to the 1850s and spans 150 years of the Natal Midlands’ family history as the group settled and farmed land in Estcourt, the former Colony of Natal.

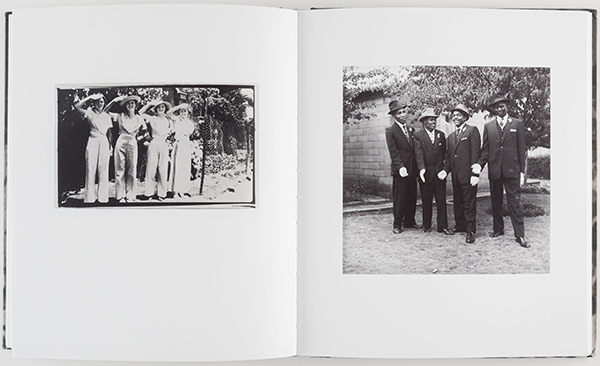

Spread from Tamsyn Adams and Sophie Feyder, Commonplace, Fourthwall Books, Johannesburg, 2016

With rich compilations from these two collections, Commonplace embraces quotidian moments, both despondent and jubilant, experienced by members of the different communities. Set against the backdrop of the social-documentary and photojournalistic heritage that often dominates South African photographic imagery, this book presents a different visual layer through which to understand the country’s complicated past. Replete with a variety of characters and compositions, Commonplace balances not only the differing social, racial, and ethnic circumstances of the apartheid era, but also the materials and objects of their lives.

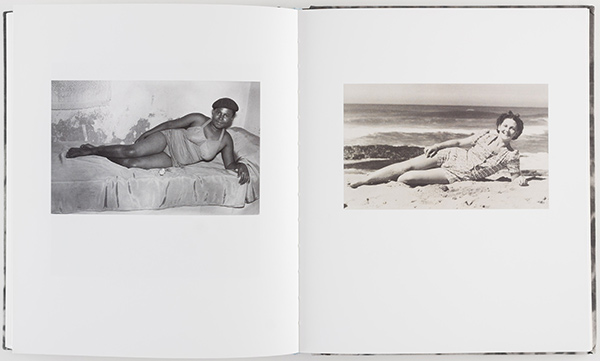

Spread from Tamsyn Adams and Sophie Feyder, Commonplace, Fourthwall Books, Johannesburg, 2016

Differing in format, tonal range, and size, the photographs interact within each collection, and more subtly, in varying visual sensibilities. Occasionally a photograph is presented with its well-worn edges, borders, and jagged corners clearly visible. This appearance hints at differing temporal contexts, and provides a material reminder of the eyes and hands that engaged with these rich objects before our own—leaving behind the “trace of relatives, loved ones and friends who once, long ago, stepped out in front of a camera” (as stated in the book’s postscript)—and of those who handled the photographic products after the fact.

Sharp juxtapositions of family gatherings, intimate couples, or reclining feminine beauties across color lines and the rural-urban divide present ambivalent and, at times, beautifully fragmented representations of life within South Africa. Rhythmic echoes across a range of sartorial choices—from canes and hats or tailored suits to striped and spotted skirts—flit across decades and communities, providing playful visual cues through which to read form and self-making anew.

Undated photograph, South Africa

Courtesy the Drummond-Fyvie collection

At its core an exercise in deconstructing and parsing the components of a photo album, Commonplace elegantly destabilizes essentializing narratives of social life and subjectivity during apartheid—but to what end? With minimal, informative texts relegated to the back and printed on a thinner manila paper, the punch of the postscript and supporting essays pales in comparison to the rich, luxurious reproductions on matte paper that populate most of the publication. Through thought-provoking pairings, Adams and Feyder claim that the photographs begin “to suggest the varied ways in which lives lived in different times and places, and under very disparate circumstances, might nevertheless be tied to each other—if not in a common place then at least in their commonplaces.”

Again and again, we face these private moments of people’s lives, and yet, are left wondering how a “commonplace” can provide a prudent point of parallel, or contact, while still honoring the heartbreaking ruptures and tensions writ large throughout South African history. Perhaps Adams and Feyder prefer to leave these strings untied, as we continue to reckon with the social and spatial aftermath of the apartheid area in contemporary South Africa, and instead focus their offering on a more careful consideration of the country’s history through personal images—an exciting and worthwhile endeavor in itself.

Commonplace was published by Fourthwall Books in 2016.