Finding Euphoria and Community in Rave Culture

On the road with Vinca Petersen, who chronicled the raves, free parties, and traveling sound systems of ’90s-era Europe.

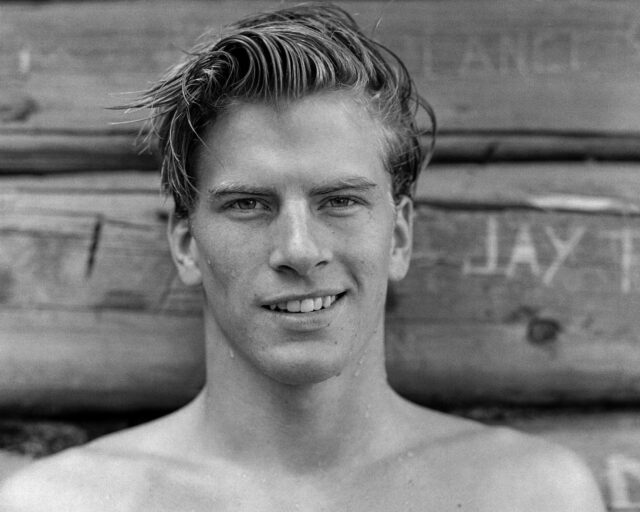

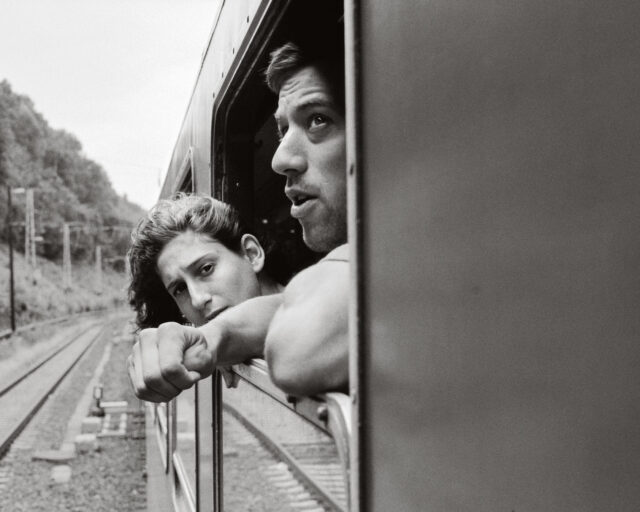

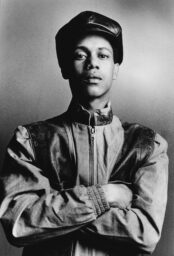

Vinca Petersen, from No System (Göttingen: Steidl, 1999)

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 224, “Sounds,” fall 2016.

Vinca Petersen didn’t set out to be a photographer. Her pictures began as a visual diary, documenting her leaving home at the age of seventeen, moving into a London squat, and becoming involved in the free party scene that blossomed across Europe in the 1990s. She has built up an impressive archive that records the techno-fueled raves and the lives of the travelers who organized them, but she started taking pictures primarily as a way of recording her own life, preserving her memories of the parties, memories which otherwise—as anyone who has danced all night will know—tend to become a bit blurry.

In the U.K., free parties grew out of the rave explosion of 1989, when crowds of up to twenty-five thousand people would gather in the English countryside for illegal all-night events fueled by MDMA and techno music. Although the primary impetus was hedonism, it developed into an exhilarating wave of mass civil disobedience in which Britain’s young briefly united and partied in defiance of the Conservative government, which throughout the 1980s had thrived on divide and rule. When the authorities finally realized this was a battle they couldn’t win and consequently relaxed restrictions on dancing and drinking, most of these revelers returned to the cities and to newly legal, all-night dance clubs. But a marginalized minority—with no jobs to fund expensive nightclubs, and a liking for the vagabond lifestyle—took to the road and continued putting on free techno parties in the countryside. They organized themselves as sound systems—a term taken from reggae music that encompasses DJs, rappers, huge speakers, and all of the technology needed to put on a party anywhere, indoors or outdoors.

Petersen had become involved in this scene while still in her teens in London. She did some modeling and as a result met the renowned fashion and documentary photographer Corinne Day, whose work had reacted against the gloss and artifice of the 1980s by exploring a different kind of beauty: young and edgy, but also awkward and flawed. The raw, personal style of Petersen’s photographs fit into this new aesthetic, and Day encouraged her to make more, giving her protégée film and even cameras. In 1994, when new, draconian laws were passed to suppress free parties in the U.K., most of the sound systems Petersen knew fled to mainland Europe. She followed soon after, taking her camera with her, and remained on the road for nearly a decade. Everyone in the free party scene had their own stories, their own reasons for staying on the move, from ideology to a simple lack of money to a yearning for freedom. Petersen enjoyed the lifestyle: “I liked the earthiness of it all, and the traveling. I loved the practicalities, like finding somewhere to park for the night, finding water, going to a new supermarket to buy food, and cooking together. For me it was about a desperate need for community, I think.”

Life on the road wasn’t easy. They wandered through France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany, banding together with other sound systems to put on huge parties in remote countryside locations in the summer, then separating to seek out smaller, more urban venues, such as empty warehouses, when the weather got colder. The travelers played what Petersen describes as a constant game of cat and mouse with the police. As a result, they were wary of outsiders, especially those taking pictures. Cameras were routinely confiscated at parties, or film was removed. Of the few pictures by other photographers that exist of this scene, most were taken surreptitiously, and seem distant. Petersen’s images, by contrast, have been taken by an insider. Working with small, inconspicuous cameras, she sometimes didn’t even look through the viewfinder before clicking the shutter; other times she’d leave a camera on a bar overnight and retrieve it in the morning to see what had been recorded.

Courtesy the artist

The resulting pictures are intimate, warm, but also unflinching, celebrating the travelers without romanticizing them. Petersen shows the damage as well as the highs of drug use, the litter and destruction the travelers left in their wake, as well as the euphoria of their parties. It’s a time and place that already feels distant: a world without cellphones and distracting screens.

Petersen’s fellow travelers often criticized her for hiding behind a lens, saying that it stopped her from being fully present in the moment. “A photograph, especially if it’s not a digital one,” Petersen remarks, “is a recording of the moment for another point in time. I used to struggle with that. But then over the years, of course everyone started asking me for copies.”

Eventually she put together a book, No System (1999), going back on the road for another year in order to obtain permission from everyone featured before it was published. A second edition was published in 2020, and Petersen hopes that a new generation will see her pictures as a guide to an alternative way of life.