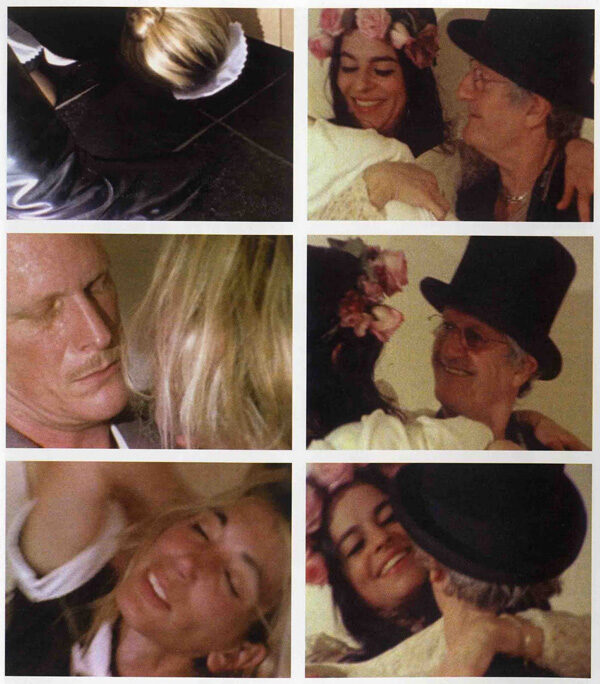

Ellen Cantor, Pinochet Porn, 2008–16

Courtesy the Estate of Ellen Cantor

Dirty Joke or Art? That was the headline in one Swiss newspaper when Ellen Cantor’s show was censored by the mayor of Zurich in 1995. Cantor, the downtown artist who died in 2013, and whose work is featured in four exhibitions in New York this fall, receives more reverence than reproach these days, but she still has an edge. Organized by Participant Inc., Foxy Production, 80 WSE Gallery at New York University, and Maccarone, together with the Cantor Estate, the concurrent exhibitions are complemented by public programs at Skowhegan and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI). The Participant Inc. exhibition, perhaps the opening salvo, sets off Cantor’s interest in explicit depictions of female sexuality as a politically transgressive act.

Courtesy the Estate of Ellen Cantor and the Charles H. MacNider Art Museum

Participant Inc. presents several dozen early Cantor paintings and sculptures. With frames bejeweled and bedazzled with pom-poms, glitter, and feathers the paintings depict lesbian orgies, seemingly from above. They also exist as fetish objects and interrupt the serious, presumably masculine dialogue of painting, and conjure what Cantor called a “girl world.” In a separate space, several vitrines display ephemera from the 1995 Zurich controversy in which Cantor’s work was declared pornographic.

© the Estate of Ellen Cantor and courtesy Foxy Production, New York

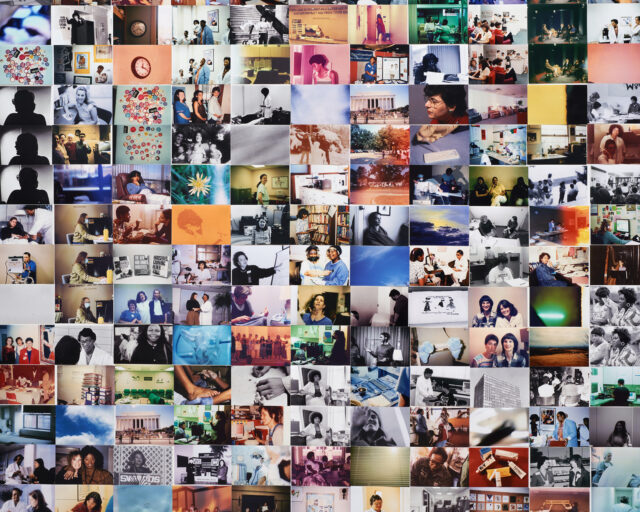

A revelatory exhibition at Foxy Production displays photo collages made during the 1990s and a three-channel video, Be My Baby, from 1999. The video, with ’90s-era special-effect flourishes, merges reels of 1960s space exploration and 1940s Hollywood movies featuring heterosexual love scenes, and asks how solitary and “masculine” gendered pursuits, like space exploration, can be understood as constructed through the lens of “feminine” and inward-looking experiences like love. It sounds trite, but Be My Baby, in fact, is personal and beautiful. For the six black-and-white photo collages, Cantor used thumbtacks to create grids juxtaposing commercially-developed snapshots of TV screens playing soap operas and porn, revealing an expanded world in which hardcore sex and treacle sentimentality coexist.

© the Estate of Ellen Cantor and courtesy Foxy Production

On the other hand, ostensibly the most ambitious of these shows, 80WSE’s Ellen Cantor: Are You Ready for Love?, which features Cantor’s last, incomplete multichannel video work, turned out to be the most opaquely curated. The five-chapter Picochet Porn (2008–16) is projected so high and so small as to be unviewable; one “chapter” plays while other projections display the titles of other chapters in bright white fonts, distracting from whatever is playing. (The exhibition does, however, include numerous rich drawings.)

Courtesy David and Monica Zwirner, New York

At Maccarone, the parade continues with Coming to Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-Plicit Art by Women, a restaging of the 1993 exhibition Cantor curated at David Zwirner gallery on the theme of sex-positive feminist artwork. Organized by Pati Hertling and Julie Tolentino (cofounder of the ’90s landmark lesbian bar Clit Club), Coming to Power encompasses several generations of feminist pioneers, from Carolee Schneemann (represented by several photographs as well as her tattered and iconic 1975 Interior Scroll) and Alice Neel (with a very early 1933 painting of a pregnant female nude), to Lynda Benglis, Louise Bourgeois, and Marilyn Minter. Not all the work in this contemporary facsimile is the same as in the original, but all date from before 1993. Together, the works give a quick guide to a second wave feminist genealogy for Cantor’s painting, photographs, and videos.

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

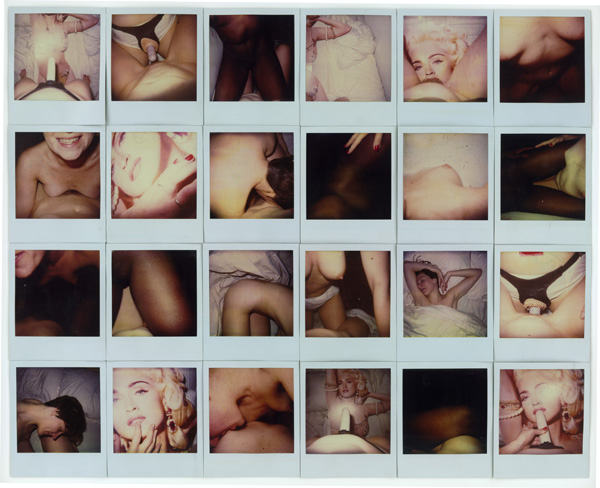

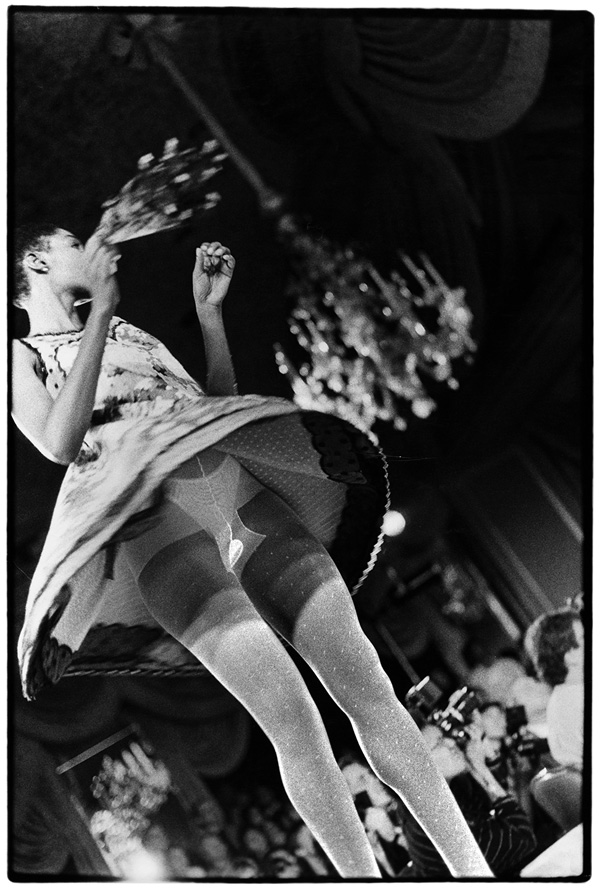

While some photographs in Coming to Power, like those by Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman, will be familiar chestnuts to New York audiences, Zoe Leonard’s upskirt shots of fashion shows from the 1990s feel especially fresh in an age of outrage at boasts of assaults carried out by Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump. And Patricia Cronin’s grids of Polaroids of herself thrusting a strap-on at the mouth of a televised George H. W. Bush, or pointing her prosthetic dick at a magazine image of Madonna, are great point-of-view shots that remind us of a time when developing film at a lab risked censorship and the immediacy of the Polaroid provided material for radical subversion.

Courtesy Maccarone

The restaging of Coming to Power also includes a lively rotation of performances. Featuring feminist artists of today, these events tend to reframe Cantor’s seeming interest in gender binaries into a more fluid and encompassing interest in non-normative gender identity. One evening featuring the dynamic Xandra Ibarra (aka La Chica Boom) brought together a large crowd. Ibarra walked the gallery wearing only yellow high heels and a prosthetic chest, laughing hysterically and dragging a large nylon sack behind her. As the crowd surrounded her in a tight knot, both protective and prurient, Ibarra entered the sack and engaged in a seemingly masturbatory episode with the wigs, ballerina slippers, pearls, and furs inside. The moment conjured the radicality of a queer downtown culture and New York communities largely lost to time—we were back in the Clit Club of the ’90s—and it was impressive that the event felt not nostalgic but living. Such interventions illuminate contemporary motivations and politics playing out over a body of work belonging to an artist no longer present, and celebrate Cantor’s newfound, and perhaps newly essential visibility, as they also mourn her loss.

*This article was updated on October 17, 2016.

Coming to Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-Plicit Art By Women is on view at Maccarone through October 16, 2016. Ellen Cantor is on view at Foxy Production through October 23, 2016. Ellen Cantor, Lovely Girls Emotions is on view at Participant Inc. through October 30, 2016. Ellen Cantor: Are You Ready for Love? is on view at 80WSE through November 12, 2016.