The Kids Aren't All Right

The Kids Aren't All Right

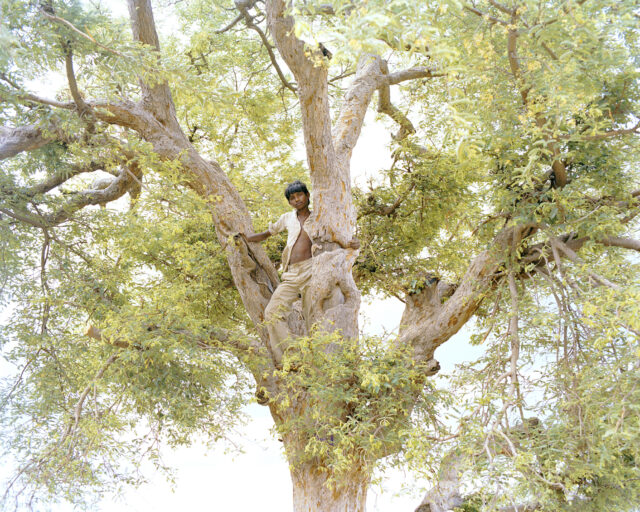

In a region where women are regarded as an economic burden, Gauri Gill photographs girls in acts of quiet daring.

One of the best things about Gauri Gill’s photobook Balika Mela (2012), named after a fair for girls in the arid state of Rajasthan in western India, is how it resists the idea that the kids are all right. In the black-and-white portraits headlining the book, rural adolescent girls are sometimes posed solo, with spare accessories—a watch, a newspaper, some plastic flowers. Some pairs and groups hold hands in obvious fellowship, while one wears paper hats. One picture shows a pair playing out heterosexual coupledom. Elsewhere, two girls staring intently into their own ring-around-the-rosie formation appear unconcerned with the world they inhabit. Solidarity, thrill, and resoluteness are all in evidence here. Yet, even while the girls’ frank gazes master the gaping desert light, these economical, almost silver-toned photographs refuse the implication of the girl ascendant.

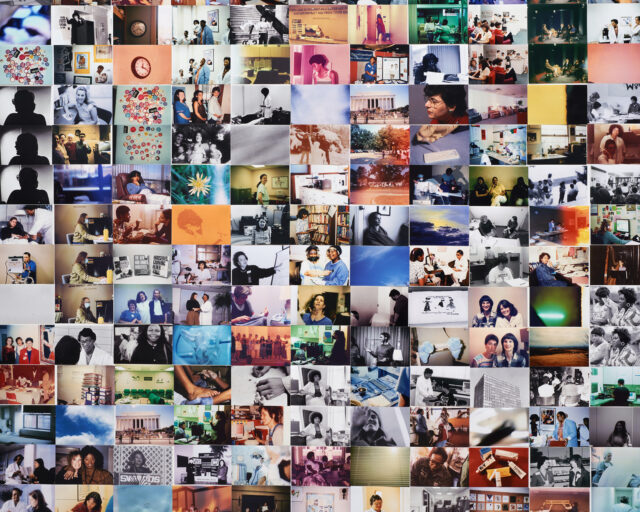

Gill’s book is a document of her collaboration with the rural non-profit Urmul Setu Sansthan, which organized Balika Mela (Girl’s Fair) in 2003, in the town of Lunkaransar, Rajasthan. Some of the over fifteen hundred girls milling around the fairground wandered into Gill’s spartan, makeshift studio for photo shoots that resulted in the black-and-white images, and several weeks of mentorship in photographic technique alongside discussions about photography. When invited back to a new installation of Balika Mela in 2010, Gill shot a new set in color, injecting unexpected theater into the girls’ hand-embroidered jeans, puffy jackets, and tennis shoes peering out from under loose pantaloons. The most swaggering image is not of the girl straddling a motorbike, but of a pair in blue, the seated girl slouched like a hip-hop artist, her hand lightly clasping that of an impassive escort.

Critics like to cast Balika Mela as a modern replay of the emancipatory mid-nineteenth-century zenana photo studio, where mainly female Indian photographers shot performative pictures of elite Indian concubines from palatial harems who otherwise lived in purdah (wearing the veil). The comparison ignores the fact that her subjects have nothing to do with orientalist identity politics or feudal concubinage. The images do, however, have a feel for the region’s dizzying rates of female infanticide, but also for the corollary: that women just want to be. Their skits of aspiration and quiet daring, while certainly quite a bit of fun, would also become pragmatic weapons while they eventually struggle to get jobs, as some do. Indeed, one workshop participant, Manju Saran, who went on to reject purdah after marriage, also established a successful photo studio. The book concludes with Manju’s first-person account, delivered partly in the third person, like a split personality negotiating the gap between an ideal state of freedom and the knowledge it is not quite hers yet, not unlike Gill’s portrayals of the same.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.