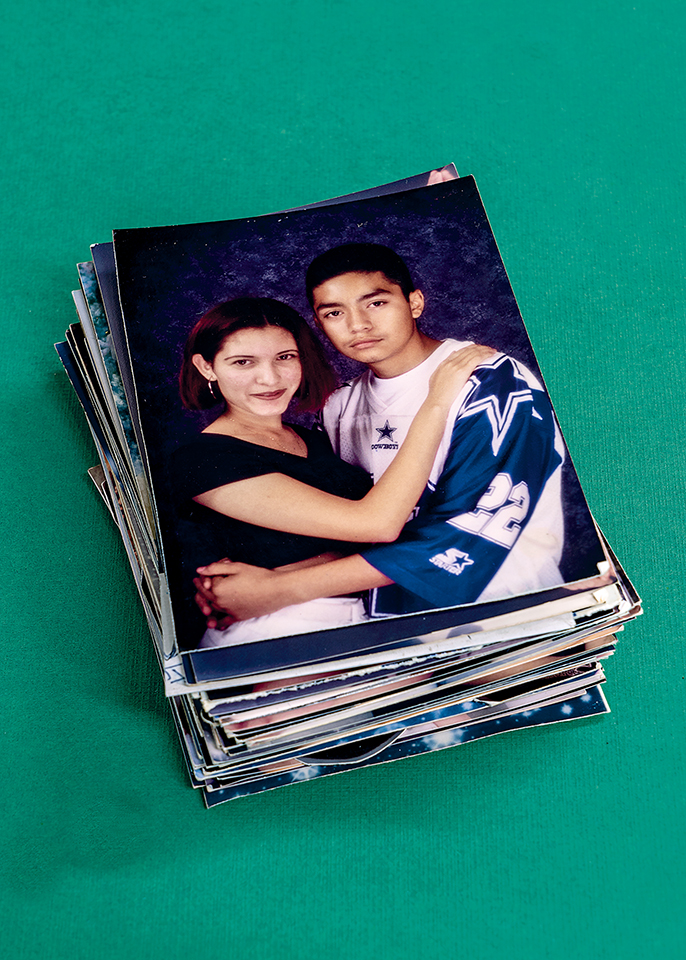

Photographs in Guadalupe Rosales’s studio, 2018

Photograph by Mike Slack for Aperture

Guadalupe Rosales moved to New York with little more than a stack of wallet-sized photographs to remind her of home. She’d left Los Angeles in 2000, a few years after her cousin, Ever Sanchez, was stabbed to death at a party. Nearing her twenties, at the beginning of a new millennium, she decided to relocate her life to New York, where she’d remain living for over a decade. During that time, as she came of age away from the violence that had marked her youth, she held on to those photographs not only as reminders of unresolved trauma, but also as important links to her past. The photographs, given to her by family and friends she had grown up with in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights, were all made in a similar “glamour-shots style” using hazy filters. In the pre-selfie era, young people would flock to their local malls wearing coordinated outfits, sharply outlined lips and eyebrows, and meticulously teased perms to pose with friends in front of ambient backdrops. The diffused lighting spared them from blemishes, including emotional ones, and saturated the images with sentimentality that with time would turn into acute nostalgia.

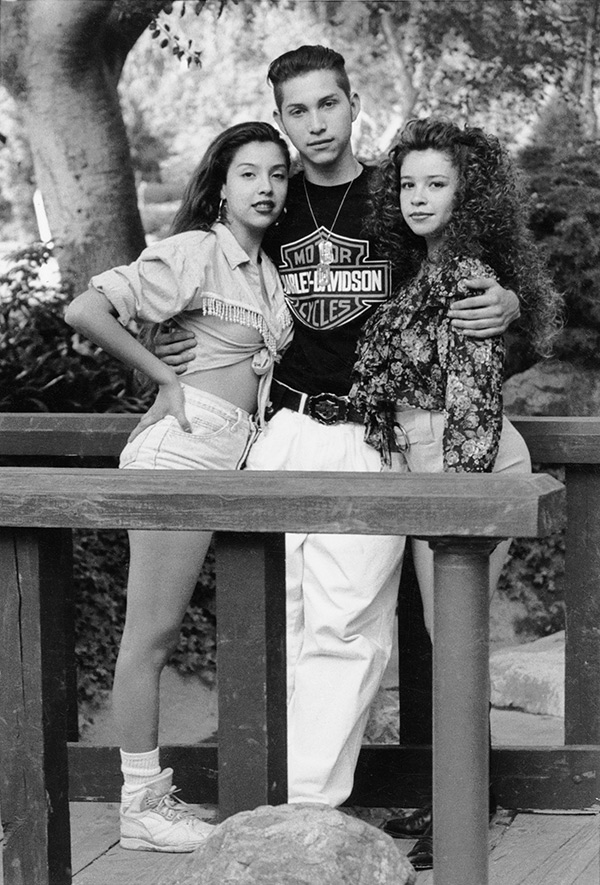

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales and Eileen Torres

For Rosales, these photographs were placeholders for a history that had yet to be told. Their pull eventually compelled her to come back home to LA. “I was thinking a lot about my crew days,” she told me. “And I was always attracted to photographs not just for their images, but also for the notes written on the back. They were like relics; they reconnected me.”

In 2015, Rosales started Veteranas y Rucas, an Instagram archive focused on youth culture in LA’s Latino neighborhoods. Its point of view is from the women’s perspective. She posted photographs from her own collection, along with brief anecdotes, in hopes of eliciting feedback. Before long, she had a steady stream of followers that eagerly shared photographs and memories of their teenage party days in LA in the 1990s. Then, in 2016, she developed a second Instagram project, Map Pointz, to collect images and memories of Southern California raves and party crews.

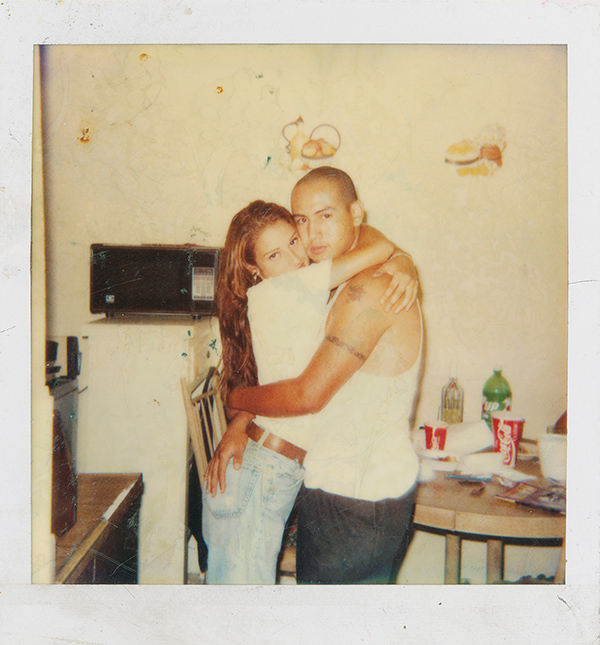

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales

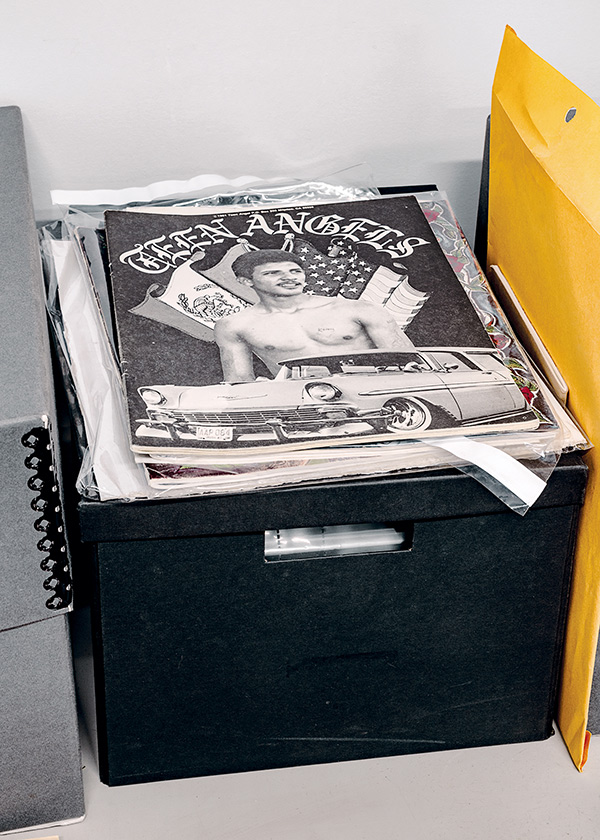

Rosales’s project is twofold: The physical collection of objects that she keeps in her studio consists of thick binders and albums filled with hundreds of party flyers, photographs, and party paraphernalia such as glow-in-the-dark beaded necklaces, pagers, and customized backpacks, along with stacks of magazines that document various youth subcultures. But it’s also her Instagram projects, Veteranas y Rucas and Map Pointz, that have quickly grown into expansive and generative digital archives of photographs that document scenes of LA. Both have become multigenerational as followers share photographs of family members and themselves, tracing as far back as the 1910s. In all of the images, we see young women and men expressing and embodying Mexican American culture through fashion and posture in their homes, in the streets, and, of course, at parties. The photographs and comments in combination begin to shape the narrative of these deeply rooted communities that have largely remained unrecognized at best and criminalized at worst.

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales and Deborah Meza

However, Veteranas y Rucas, says Rosales, was not originally conceived as an archive. While in art school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and far from home, she began with the idea of creating an installation of a teenage raver’s or party crew member’s bedroom. But she was also thinking of her work as a broader historical project, using photographs and other objects as documents to show what it was like to grow up in 1990s LA as a young woman of color. “I started the work with the intent of finding material on my own time in the 1990s,” says Rosales. “But if you don’t have the material, you can’t use it.”

Though Rosales’s process of collecting photographs of these unrecognized communities has largely been guided by instinct, it is in step with the work of radical historians such as José Esteban Muñoz, who called for building an “archive of the ephemeral.” In his groundbreaking 1996 article “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts,” Muñoz posits that contrary to traditional archives that exclude marginal communities—the poor, queer, and colored—an ephemeral archive allows us entry into transient spaces, such as dance floors and cruise spots, where we can begin to find their stories.

While the invisibility of these and other marginalized communities, especially youth, has all but erased them from official history, it also once protected them. The 1990s were dangerous times for young people of color in LA. It was a decade of increasing economic disparity, police brutality, and social turmoil that led up to and followed the 1992 LA riots, along with gang violence and rampant anti-immigration policies that prompted days of student walkouts.

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales

“Kids went underground. At raves and parties, we were creating safe spaces for ourselves when everything like the riots and Prop 187 was going on,” Rosales recalls, referring to Proposition 187, a 1994 ballot initiative that would prohibit undocumented immigrants from accessing public services such as education and health care. Rosales attended many of these parties when she wasn’t going to protests and marches with her mother and sister. Effectively, it was in the underground that youth like Rosales created a world of their own, away from the institutional establishments that had betrayed them.

Map Pointz focuses on the rave party scene. The name refers to what in the 1990s were the coordinates of a party location that could only be accessed by following a specific set of instructions. Flyers often directed partygoers to call a phone number to learn where they would receive an address for the event, usually only hours before the doors opened. The purpose was to keep the location secret from unwelcome party crashers, including police, parents, and rivals.

Party crews would often drive out into the far reaches of Greater Los Angeles, even venturing into Southern California’s Inland Empire. “Sometimes we didn’t even know where we were going. We’d just carpool and end up in places,” recalls Rosales. Very naturally, party culture intersected with Southern California’s distinct car culture. Veteranas y Rucas includes many photographs, from across several decades, of young Chicanxs posing with cars, as if this recurring shot marked a coming-of-age or, for women, a display of empowerment. Photographs of young people cruising along LA’s Eastside boulevards in customized cars show a weekly urban pageantry of polished chrome, jewel-toned fiberglass, sculpted hairstyles, and the finest hoochie garb. They were parties on wheels.

Photograph by Mike Slack for Aperture

As these underground parties proliferated and became more sophisticated, they developed an ephemeral infrastructure that suited LA’s decentered and transient character. According to Rosales, partygoers became party-promoters who created entrepreneurial opportunities for themselves; amid a barren landscape, they took warehouses gutted by deindustrialization and transformed them into temporary venues for large-scale events, turning these underground scenes into businesses. They taught themselves, and each other, skills as they photographed, laid out, and published their own magazines. They designed their own flyers, booked venues, and found creative ways to promote carefully planned events. “These parties were being organized by teenagers using their own resources,” Rosales says. “Schools were not providing us skills. The party scenes allowed us to develop these skills.”

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales and Eileen Torres

Concurrent with the rise of these cultures, print magazines like Low Rider, Street Beat, Teen Angels, and Urb thrived as they documented the various scenes and effectively trained new generations of publishers and photographers. Rosales met one of these photographers, Eddie Ruvalcaba, on Instagram and soon began collaborating with him on an installation project at Commonwealth and Council, a gallery in downtown LA. Ruvalcaba was a self-taught photographer for Street Beat. His portfolio extends beyond party scenes, including photographs of daily street life, as well as striking images of the 1992 LA riots and their aftermath. This collaboration is an example of how organic partnerships can grow out of collective archive-building processes such as Rosales’s, which are, in fact, part of a growing movement of nontraditional, DIY archive projects dedicated to recovering lost histories.

Photograph by Mike Slack for Aperture

Rosales and Ruvalcaba held one other thing in common: they were both still coming to terms with the trauma of violence and drug addiction that came to afflict so many of their generation.This is also what brings so many Instagram followers to share their experiences with Rosales, as they attempt not only to ruminate on memories of times past, but to make sense of the chaos they experienced. More than just Instagram projects, Veteranas y Rucas and Map Pointz also involve a process of healing, which is why Rosales continues to hold onto them so closely. She says that though she feels some pressure to conserve the objects in the collection she is building, she is not ready to hand them over to a formal or institutional archive. “The project is still evolving, and it’s still a part of me. I feel responsible for these things.”

Even today, Rosales guards the stack of wallet-sized photographs, keeping it within arm’s reach in her studio as if it were a deck of tarot cards. The ink of the neatly written notes on the back of the photographs is now smudged but still clearly says, again and again, “Keep in touch.” And she does.

Read more from Aperture issue 232, “Los Angeles,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.