Henri Cartier-Bresson's Glimpse of India

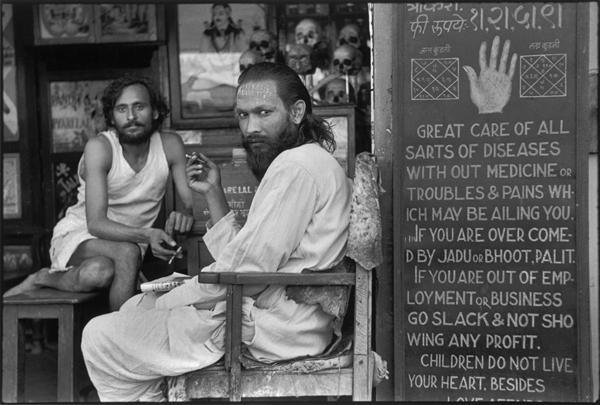

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Astrologer’s Shop, Bombay, Maharashtra, India, 1947

© the artist/Magnum Photos

In 1947, Henri Cartier-Bresson embarked on a major three-year trip to Asia, to photograph on behalf of Magnum Photos. The same year, he cofounded Magnum and his early artistic work from the 1930s and ’40s was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in an exhibition organized by Beaumont and Nancy Newhall. In part thanks to his first wife, the Javanese dancer Ratna Mohini, Cartier-Bresson was particularly interested in Asia and the massive social and political changes resulting from the postwar collapse of colonial empires. Cartier-Bresson’s first stop was India, just after the country gained independence from Great Britain. Centered on his images of Mahatma Gandhi and his funeral procession, the exhibition Henri Cartier-Bresson: India in Full Frame, currently on view at the Rubin Museum in New York, is a sweeping chronicle of the iconic photographer’s sojourn in India.

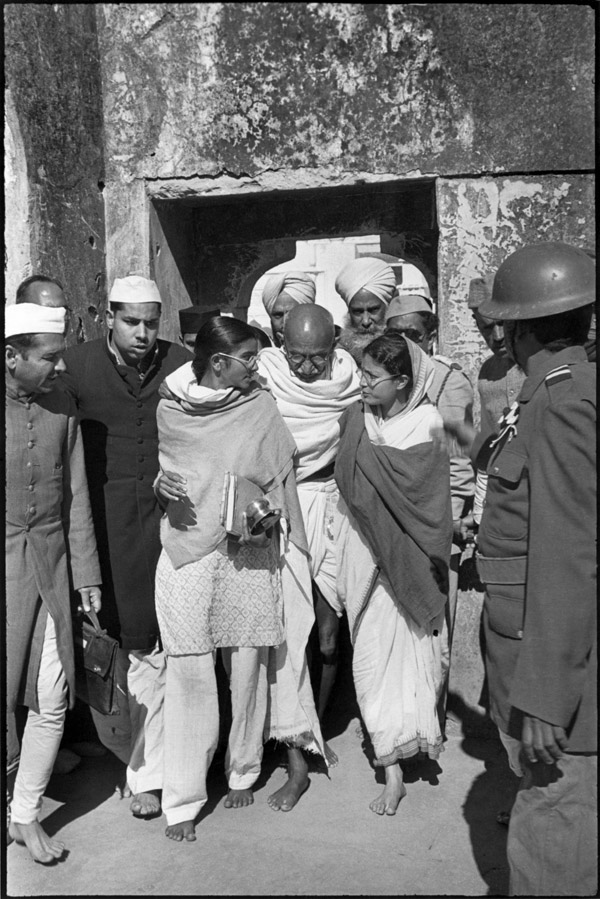

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gandhi leaving Meherauli, Delhi, India, 1948

© the artist/Magnum Photos

The day before Gandhi’s assassination, Cartier-Bresson photographed the leader, who had been fasting to call for an end to the violence over the India-Pakistan partition, as he was physically—and perhaps emotionally—supported by his nieces. Cartier-Bresson returned the next day to interview Gandhi about the fast. On January 30, 1948, hours after their conversation, Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu nationalist. In the aftermath, Cartier-Bresson returned once again to Birla House to document Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s announcement of Gandhi’s death. Cartier-Bresson’s quiet pictures of Gandhi’s body lying in state led to a commission from Life to document the funeral. (The February 16, 1948 issue included nine of Cartier-Bresson’s photographs, compared to only five by Margaret Bourke-White, despite her close relationship to the magazine.) Cartier-Bresson captured silence and grief in a moment of chaos and noise. In Train Carrying Gandhi’s Ashes (1948), for example, a single figure stands in a mass of bodies with a look of anguish inscribed on his face.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Train Carrying Gandhi’s Ashes, Delhi, India, 1948

© the artist/Magnum Photos

India in Full Frame, curated by Beth Citron, touches upon Cartier-Bresson’s well-documented awareness of his privileged position as a white, male foreigner. As he photographed the funeral proceedings—the cremation and scattering of the ashes—Cartier-Bresson attempted to remove himself from his place of advantage; he tried not to photograph the crowd from above, as he did not wish to project a western gaze. Cartier-Bresson’s awareness, however, does not extend to all his work in India, and the exhibition does little to challenge the photojournalistic frame within which he was working. By this omission, the suggestion is that Cartier-Bresson’s images from India avoid the clichés of journalistic photography.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Untitled, Madura, Tamil Nadu, India, 1950

© the artist/Magnum Photos

In the exhibition, a handful of photographs lack context that would help them subvert such clichés. An untitled photograph from 1950 shows a malnourished child held by a woman, presumably his or her mother. The woman’s hand—monumental in comparison to the child’s frail body—cradles the head of the child, but little detail is provided by either the photographer himself or the curator. In effect, the child becomes a nameless, starving body and fuels the West’s stereotyped, reductive perception of India. As Jacque Rancière has noted, there are “too many nameless bodies, too many bodies incapable of returning the gaze that we direct at them, too many bodies that are an object of speech without themselves having a chance to speak.”

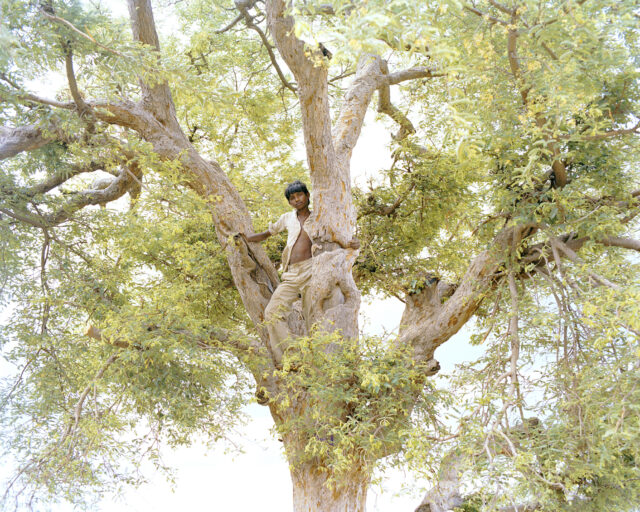

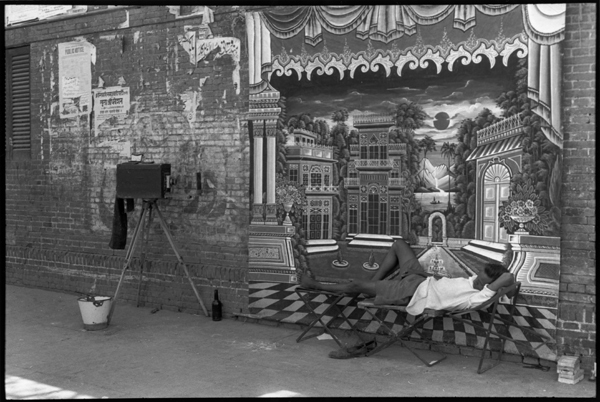

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Street photographer in the old city, Delhi, India, 1966

© the artist/Magnum Photos

While most of the photographs presented in India in Full Frame are situated more closely along the photojournalistic line than the artistic, works like Astrologer’s Shop (1947) and Street photographer in the old city (1966) resist the journalistic sensibilities Cartier-Bresson largely employed in India and lean more toward his earlier, surrealist work. Such images exist outside the typical visual associations of photojournalism, such as starving children and beggars with emaciated bodies. Street photographer (1966) displays Cartier-Bresson’s surrealist sensibilities by combining an imagined and real background. The work is a subtle, perhaps unintentional nod to the history of Indian studio photography practices.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Refugee camp, Kurukshetra, Punjab, 1947

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Cartier-Bresson portrayed India as he found it, capturing the business of everyday life. He photographed everything from refugees performing their daily exercises, to women spreading saris out in the sun to dry. While India in Full Frame is centered on the mythic figure of Gandhi and the outpouring of emotion after his death, the exhibition also reveals Cartier-Bresson’s struggle to interweave art photography and photojournalism—an unwavering commitment, as he put it in his 1952 essay, “The Decisive Moment,” “to preserve life in the act of living.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson: India in Full Frame is on view at the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, through September 4, 2017.