What Happens When the American Dream of Homeownership Reaches Mexico?

For more than a decade, Alejandro Cartagena has photographed Mexican suburbs transformed by the rapid construction of new homes.

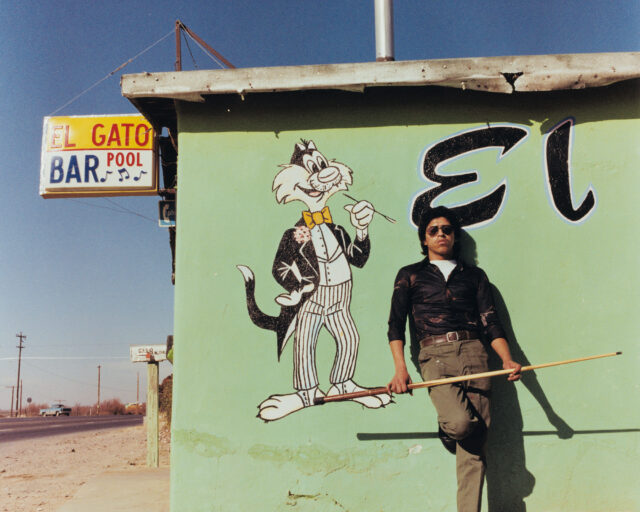

Alejandro Cartagena, Apodaca, 2007

The photographer Alejandro Cartagena knows you want to go home. You yearn for a house that really feels like home—an affordable space of serenity or happy chaos, with easy access to work, clean air, and clean water. Where you can become fully human and maybe raise a family. Not a site of destruction or pollution. Not a place that will bankrupt you or pen you in or poison you. Home.

The failure of the world’s metropolitan areas to fulfill this dream for all of its residents drives Cartagena’s work. Cartagena, who was born in the Dominican Republic in 1977 and now lives in Monterrey, Mexico, has photographed Mexican suburban architecture and its housing-challenged inhabitants for the past fourteen years. His images of cheap structures and exhausted commuters critique the international club of politicians and urban planners whose model of quick and unequal development has left many people bereft of a safe place to call home. The housing boom started in Mexico in the early 2000s, when aspiring landholders began acquiring properties financed by mortgages.

Courtesy the artist and Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles

Courtesy the artist and Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles

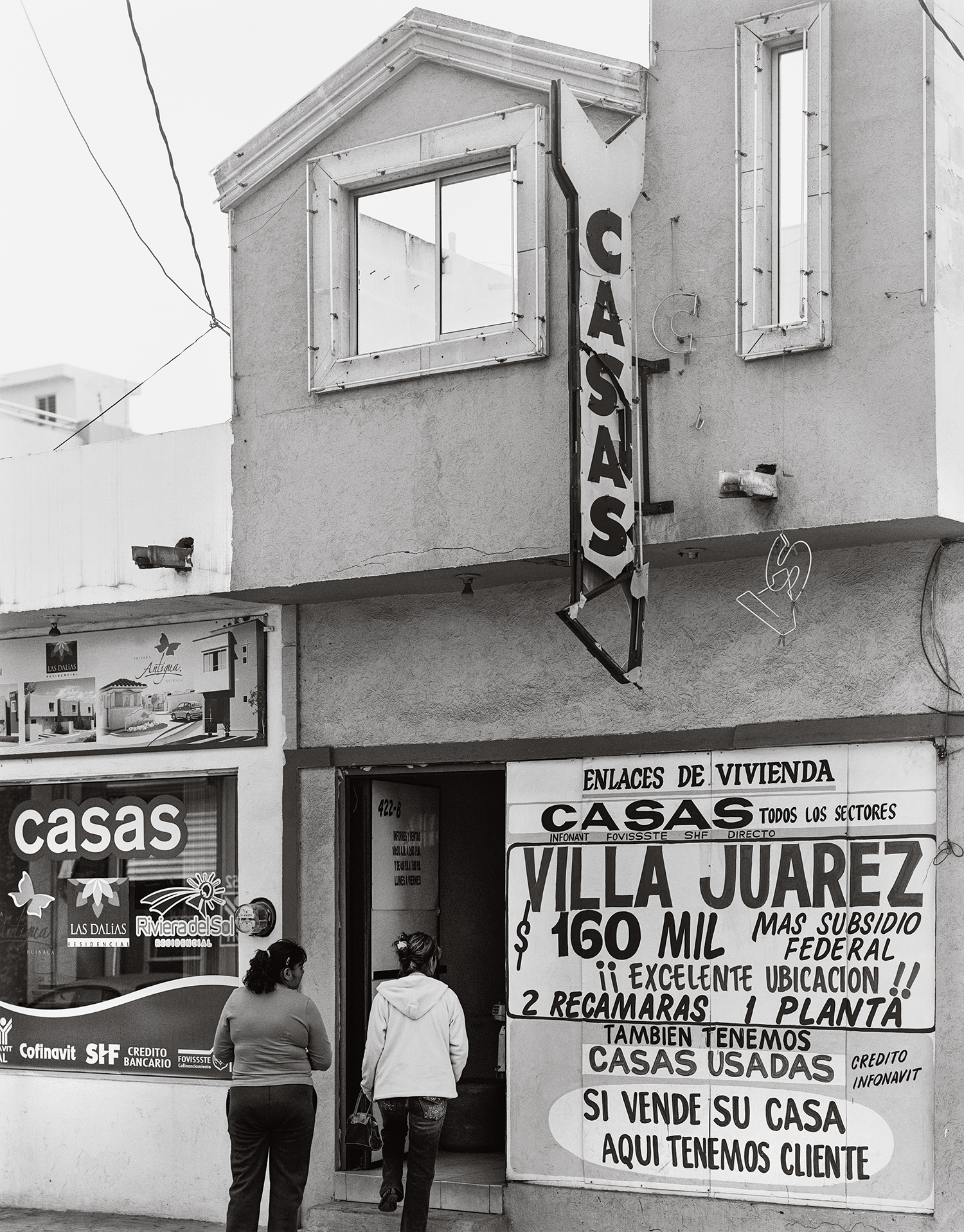

Though this practice has allowed more people to acquire homes built out of permanent materials, government loans are only available to those with salaried employment, a status that sixty percent of the Mexican working population can claim. Salaried workers thus possess a greater likelihood of living in such sound structures than those surviving in seasonal or gig economies.

“My images are trying to present the more complex situation that’s never told in the commercial and ideological stories of homeownership,” Cartagena says. “The idea of buying a home is that it will bring social mobility, safety, love, a family, the whole Hollywood, Disneyland version. But there exist loopholes in this story, particularly in how homeownership had been photographed, always from the outside.”

Courtesy the artist and Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles

Courtesy the artist and Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles

In 2010, Cartagena published Suburbia Mexicana: Fragmented Cities with Daylight/Photolucida. This project recorded the suburban sprawl in Monterrey, a city that had 339,282 residents in 1950, but today lodges over 3.8 million. Suburbia Mexicana features images of 328-square-foot houses that typically billet four to six people and look like the cookie-cutter “little boxes” lampooned by folk singer-songwriter Malvina Reynolds in her song by that title. In 2014, Cartagena self-published Carpoolers: on Monterrey’s Highway 85, a route carrying men from their homes in the new suburbs to their work sites, he captured his voyagers lying down, eating, and sleeping in the backs of trucks, often amid the detritus of their jobs.

Courtesy the artist and Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles

Courtesy the artist and Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles

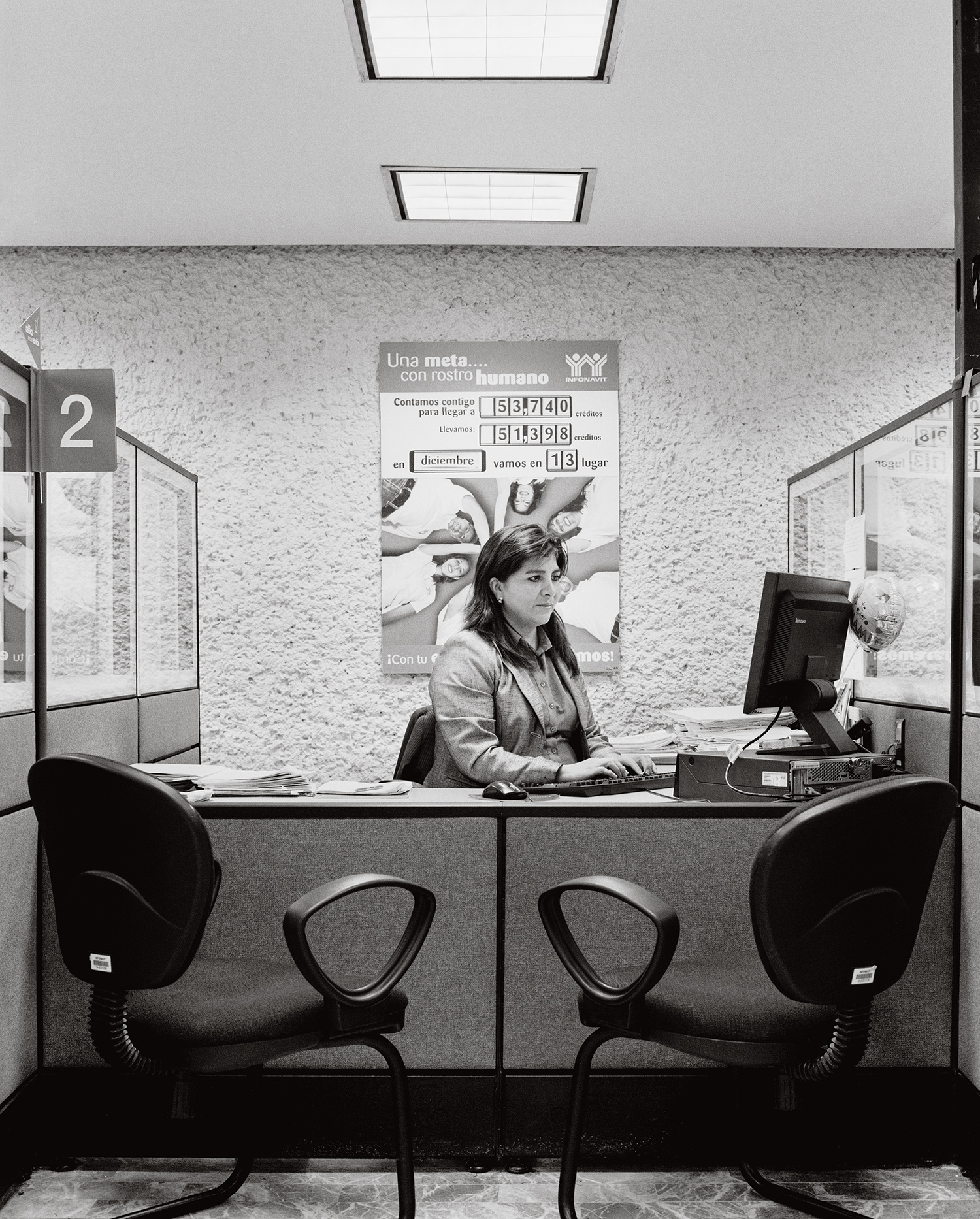

Cartagena’s recent series A Small Guide To Homeownership: Case Study: Mexico (2019) takes the form of a photo-collaged proto-Dummies manual that blithely, and blindly, gives tips on financing residential real estate and managing thirty-year, fixed-rate mortgages. It tucks images from Suburbia Mexicana and Carpoolers into found text from home-buying guidebooks. In a particularly lacerating chapter, Cartagena layers the pictures of the little boxes over the real estate–industrial complex’s conventional rah-rah fantasies, which counsel that if your family has “two who cook, you need . . . a big kitchen,” and if you have “small children, you need . . . lots of bedrooms,” conveying how unrealistic the own-your-own-home cult can be.

Cartagena observes that his photographs fill in the gaps left by government and development propaganda that pushes the idea of homeownership as an unqualified good. “If you connect a picture of a house in the suburbs with a picture of carpoolers, with a picture of a desiccated river—those images weren’t meant to be together,” he says. “But if you connect those dots, the story becomes more complex, and the questions open up to ‘What are we really doing?’”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home.”