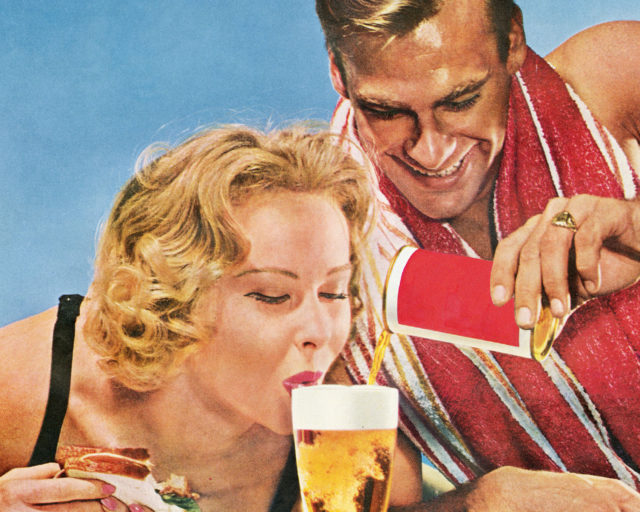

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Every Moment Counts (Ecstatic-Antibodies), 1989

Courtesy Autograph, London

If you step out of the tube station at Old Street, in London’s East End, and wander the narrow lanes of Shoreditch, with their chic gastropubs and boutique hotels, you might suddenly find yourself in front of an inviting yet commanding building, its slate gray and glass distinct from the nineteenth-century stock brick of the neighborhood. Rivington Place, as it’s known, was built by David Adjaye in 2007, and it’s the home to Autograph, the influential organization that supports Black photographers through exhibitions and publishing. Founded as an agency in 1988, Autograph ABP (Association of Black Photographers) intended to advocate for Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) artists by commissioning new work and producing traveling exhibitions. Publications, especially artists’ monographs, were central. “The model was massively ambitious,” Mark Sealy, the longtime director of Autograph, recalled this spring, speaking over Zoom from his house in South London. “The aspiration for publishing was always on the table.”

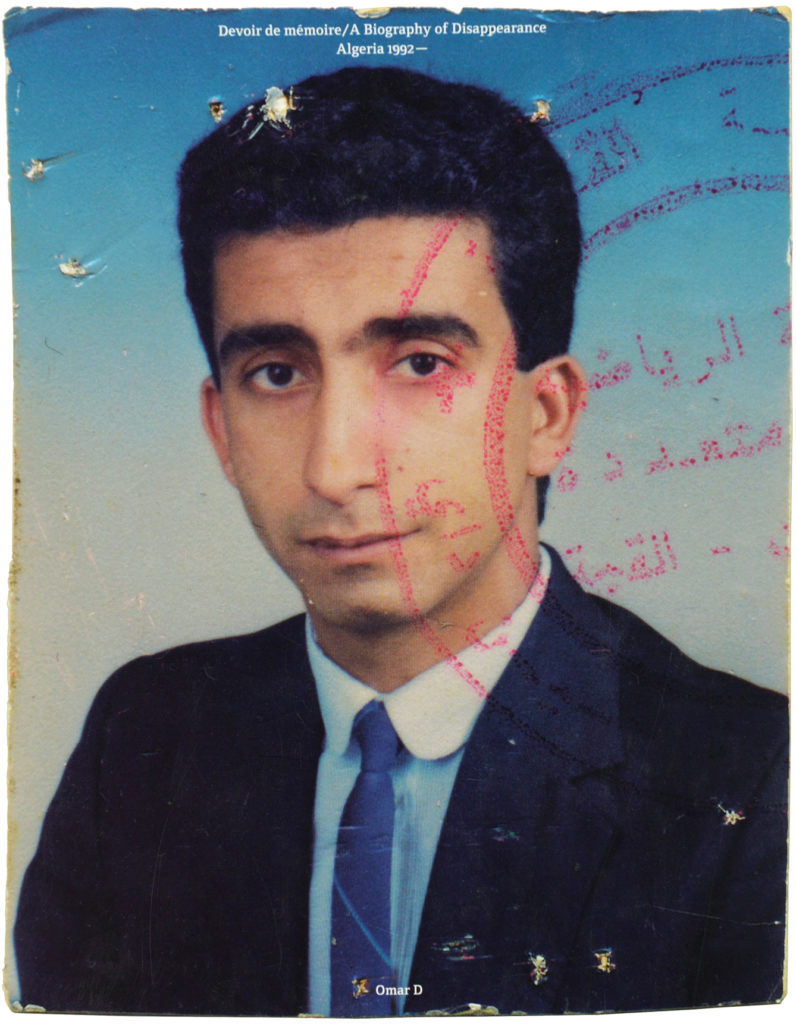

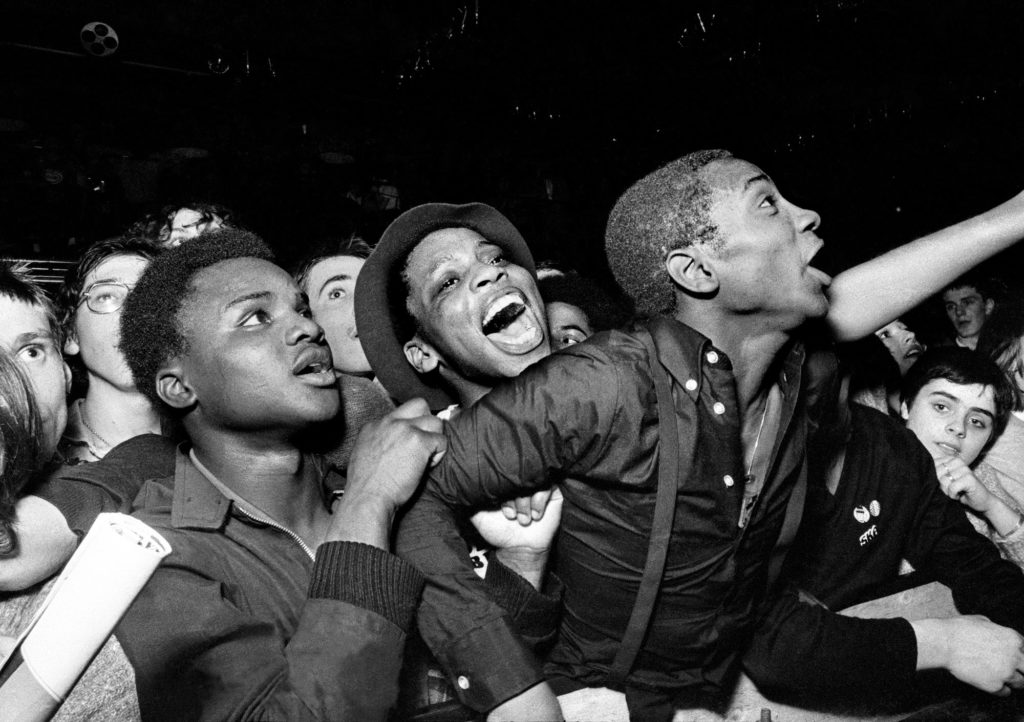

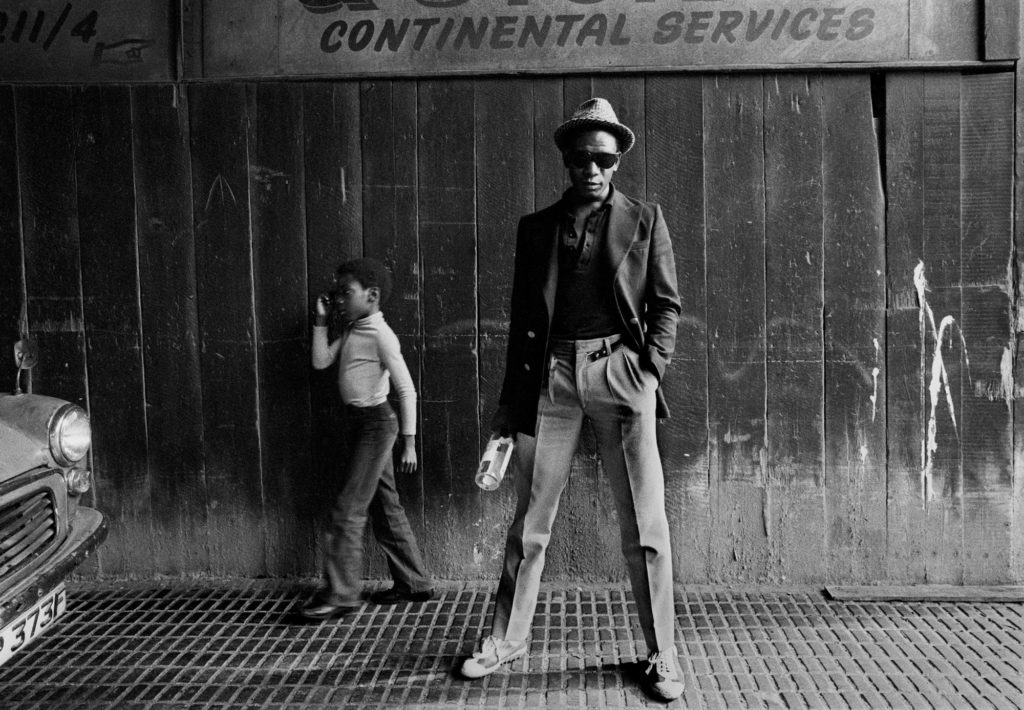

Among Autograph’s most influential titles are monographs by the late Rotimi Fani-Kayode (an Autograph founder), Omar D, Joy Gregory, Youssef Nabil, Yto Barrada, Syd Shelton, and Sunil Gupta. Autograph has collaborated with the Power Plant and the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto, and the Photographers’ Gallery in London, on major group exhibitions and studies of historical archives. One measure of Autograph’s sustained, thirty-year commitment to the visibility of Black artists, and the centering of identity and human rights, is its reverberation in establishment British art museums. A decade before Zanele Muholi’s solo show at Tate Modern and James Barnor’s at the Serpentine Galleries, Autograph presented exhibitions by both photographers; before Barrada and Gupta were renowned internationally, they worked with Autograph. Sealy knows about the long game: he spent much of his career, as a scholar, curator, and arts leader, trying to convince cultural institutions of the importance of diversity. It’s why Autograph’s elegant gallery and offices on Rivington Street—which represent the manifestation, in the form of a publicly funded arts building, of the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s ideals about difference and belonging—will welcome you, and challenge you.

Brendan Embser: In the 1980s, when the people who started Autograph were getting going, were there any publishers in the UK who were regularly putting out monographs or studies of Black image makers?

Mark Sealy: There were one or two. Some photographers had got their act together to self-publish. Armet Francis, for example, had published his book The Black Triangle [Seed, 1985]. And Clement Cooper had been published by Cornerhouse Publications. Rotimi Fani-Kayode published his monograph Black Male/White Male [1988] with Gay Men’s Press. But there was certainly a gap there to be filled.

Embser: Was there a culture around photobooks? For example, for Black American photographers, specifically, there is an iconography that emanates from The Sweet Flypaper of Life [Simon & Schuster, 1955]. In the UK, were there any similar books that held the same power for Black British artists?

Sealy: For me, it was Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage [Random House, 1967]. In the UK, we were much more focused on what was happening in South Africa, especially in the ’80s, with the ANC, the demonstrations in Trafalgar Square every day, with the popular culture being really aligned with the ideas of people like Steve Biko and Nelson Mandela, who was still in jail. Sweet Flypaper was in the conversation, absolutely. But to actually see it, to get hold of it, I don’t think I actually saw an original copy in the flesh until I knew what I was looking for—it was not something you could find with ease.

Embser: Autograph began publishing books soon after the organization was founded. Were books a way to allow projects to travel beyond the space of an exhibition?

Sealy: The most important thing that we did was publish. I always thought that publishing was kind of the cherry, the golden fleece of a cultural organization—if we could get there, in a meaningful way. I was very keen to make sure that everything had an ISBN, because if they have an ISBN, you legally have to register them with the British Library: it lives forever, rather than the ephemeral nature of an exhibition coming up and down and being left with an invite card and the memory of people, or a review.

It was very difficult to go out into the world and sell exhibitions in London, Manchester, or Liverpool, of Black photographers’ works, because the answer would be, “It’s not very good,” or, “We don’t have an audience for that,” or “Why would we do it?” It was very, very derogatory in terms of the reception of the work. So the book was a way of at least, then, syndicating their work—get them out there, and then they’ll become alive in the world.

Embser: It’s interesting that you emphasize the ISBN, because I was able to find Autograph’s books on WorldCat and Amazon because of that—they exist in the tentacles of the internet as a result of this data that you entered early on.

Sealy: Yeah, thank God.

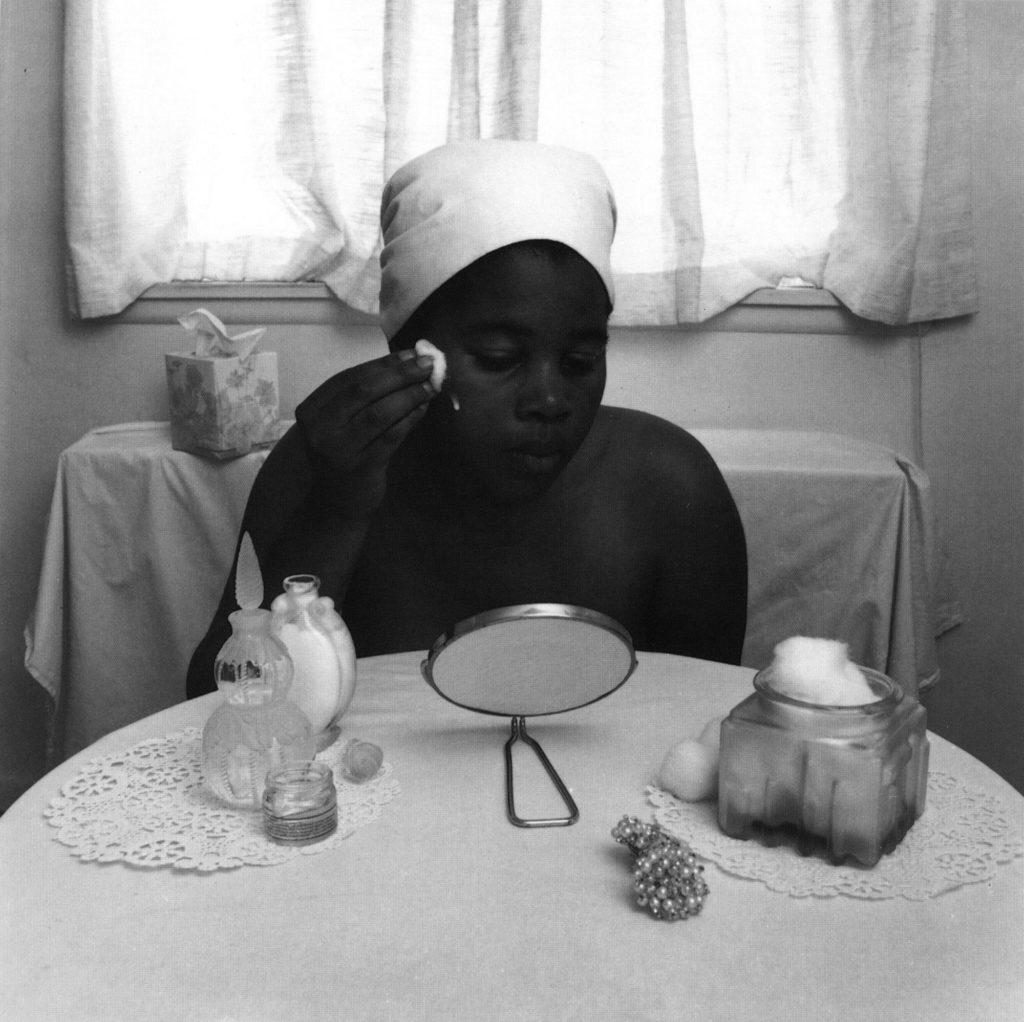

Courtesy the artist and Autograph, London

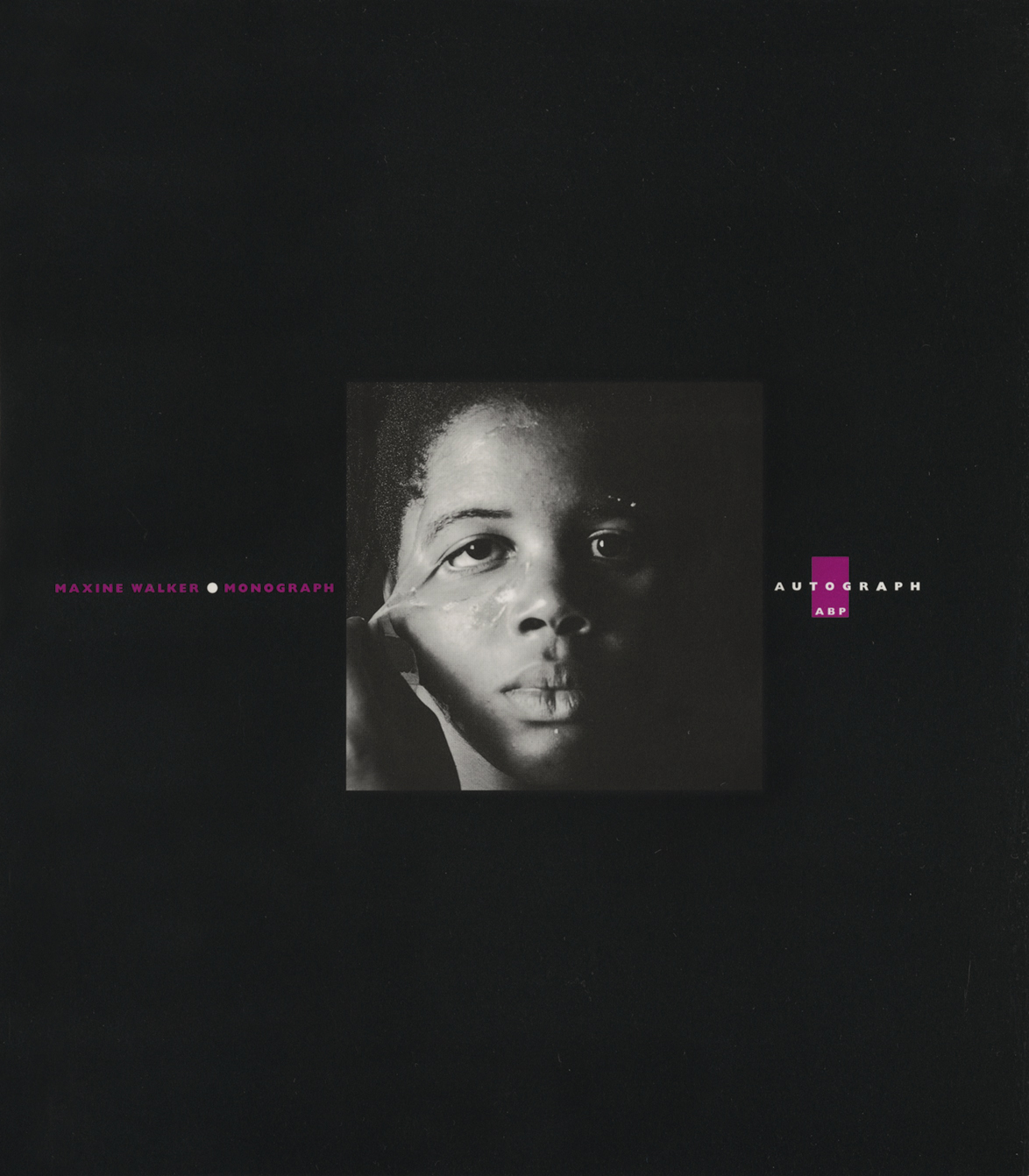

Embser: In the late ’90s, Autograph did a number of small monographs that were between twenty or thirty pages each, for example, by Eileen Perrier and Maxine Walker [both 1999]. Were those small books among their first artist publications?

Sealy: Absolutely. In many instances, that monograph series, I think, is really important. I think that is one of the first monograph series dedicated to Black photographers.

Embser: And did those publications often arise on the occasion of an exhibition that Autograph had organized, or were they separate initiatives?

Sealy: Often it was just, “You’ve got enough work, let’s do it.” Or we would commission a new body of work and find a permanent way to record it.

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Embser: Can you talk about the range and aesthetic of Autograph’s books? You have exquisite artists’ books, for example—I have a copy of Yto Barrada’s A Life Full of Holes / The Strait Project [2005].

Sealy: Oh, yeah, keep that.

Embser: Apparently it’s five hundred dollars on Amazon!

Sealy: I thought Yto’s look at the whole issue of migration in the Maghreb, in Morocco, of “the burnt ones,” was such a powerful project. But also, done through a lens of ennui, a nation’s depression. And in many ways, the book launched that body of work.

Embser: Rotimi Fani-Kayode and Alex Hirst: Photographs [1996] was copublished by Revue Noire in Paris. How did this book come about?

Sealy: Rotimi died in ’89. Alex, his partner, was looking after the estate, but he died of AIDS in 1992. I made a solemn pledge that I would advocate for the work and try and bring it into the public sphere, in the best possible way we could. I was lucky enough to meet the guys at Revue Noire—Simon Njami and Jean Loup Pivin—who also appreciated the work. They saw Rotimi’s radicality as a queer African guy, and they really appreciated that. And that was good. They wanted to invest in the politics of that transgressive relationship. Which, of course, they identified with as well, for personal, cultural, and political reasons. You know, what’s interesting for me, when we talk about diversity in our institutions and all that stuff? It really is just to do with the people in the room. If people get it, then we get it.

Embser: Absolutely.

Sealy: If they’re not in the room, then we have to sell so much and work so hard just to try and have the conversation, right? The moments of success for Autograph happened because sometimes the people in the room kind of got it, you didn’t have to work so hard. When you literally fight for visibility, what are you doing? That sense of urgency gets interpreted as anger, and it’s wrong, because it’s not. It’s to do with, do you get the urgency of what we’re trying to talk about here? And it’s thirty years of that sense of urgency, and we go round in circles. And we’re in another cycle now, which is interesting. I’m hoping that with each turn, the turn gets easier, or a bit faster, so that things can change. I think publishing is part of that, helping people. That’s why Sweet Flypaper is so important, that’s why House of Bondage is so important. That’s why Rotimi’s book is so important.

Embser: In addition to artist monographs, Autograph has also published compendia on really difficult, hard-hitting issues around human rights. Why is copublishing important for these kinds of research-based projects, where you bring together lots of ideas, some of which will be challenging for audiences?

Sealy: Human Rights, Human Wrongs [2013] was the result of three years working in the Black Star Collection at the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto. I wanted to try and make a case for how awkward the archive is, in terms of documentary photography concerning the image of the Black subject. Always framed, always debased. And it was great that a university gallery could try and understand that conversation, which was nuanced and difficult. As we develop a project, the ideas do need to be encapsulated beyond the show.

With a copublishing project, you share the risk in terms of the investment. You can do much more in partnership. You can take a thirty-thousand-pound production, and it’s fifteen each. Sammy Baloji and Filip De Boeck’s book Suturing the City [2016], for example, has about four or five different stakeholders in there. There’s his gallery, there’s the Power Plant, and the dealers; they invest in it, they get their amount of copies. But Autograph was the publisher, and we thank them very much for supporting it. And sharing that, sharing that risk means things can happen.

Courtesy Autograph, London

Courtesy Autograph, London

Embser: There’s a sense of idealism with Autograph’s publishing, but also perseverance, trying to get stories into the world. How does this extend to marketing?

Sealy: We sell things directly. We don’t distribute in a really aggressive way. We often do around about a thousand copies of a book, and the idea is that they’re not really made to make money. If they make money, that’s great, and they often do. Like, for example, Lina Iris Viktor’s book Some Are Born to Endless Night—Dark Matter [2020] is sold out. Syd Shelton’s Rock Against Racism [2015]—off, gone. We could reprint them, but that’s not the purpose. The idea is to just get them circulated, get them out there. And they’re great success stories, you know?

Commissioned by Autograph. Courtesy the artist and Autograph, London

Embser: What are a few of your favorite Autograph titles, either because they’re really beautiful, or because you know that they’ve had a lasting impact—you see them on your shelf, and it just fills you with joy or pride?

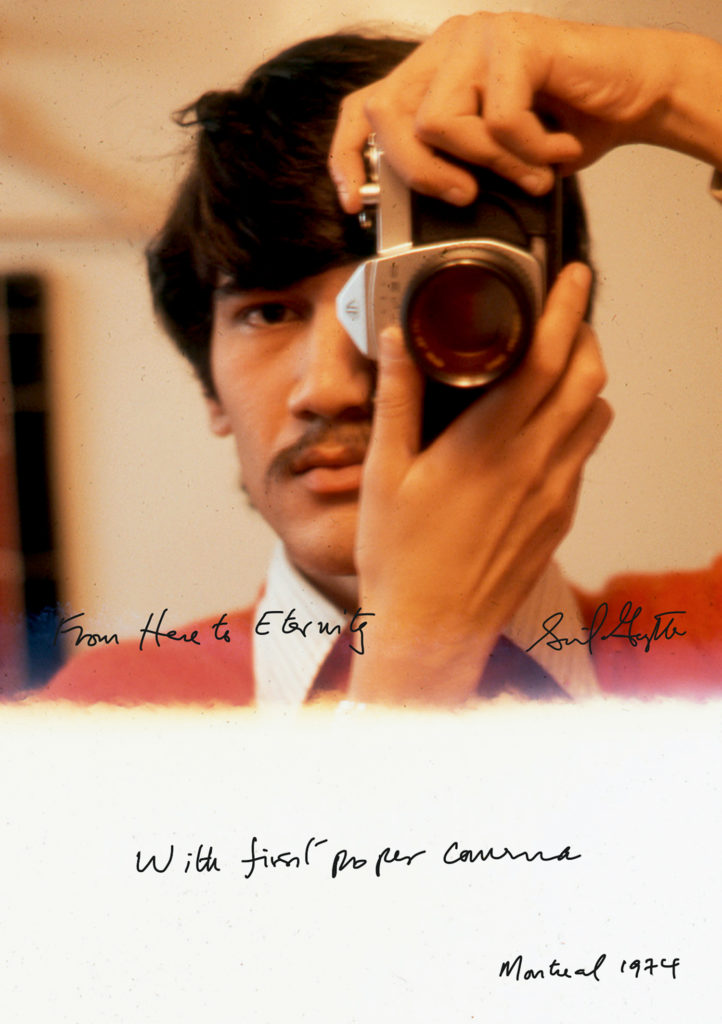

Sealy: I enjoyed watching the impact of Yto’s book; that was very nice. Sunil Gupta’s recent book on his ephemera From Here to Eternity [2020] is beautiful. But I don’t think there’s any particular one that I would champion. In that series, the artists do such different kinds of work. One of the things I try and do at Autograph is to talk about Blackness as a politically conscious space. I can’t help but think how divisive racial politics are, and the labeling of BAME (Black, Asian, and minority ethnic), and how things get segregated. I always wanted to build an inclusive conversation around consciousness and thinking, and I still think that one of the few frames by which I can join the dots across that thinking is the lens of human rights.

This piece originally was published in Issue 019 of The PhotoBook Review.