How Claudia Gordillo Documented the Realities of Life in Nicaragua

Whether photographing armed conflict or religious rituals, Gordillo observed Nicaraguan society from a close yet critical distance.

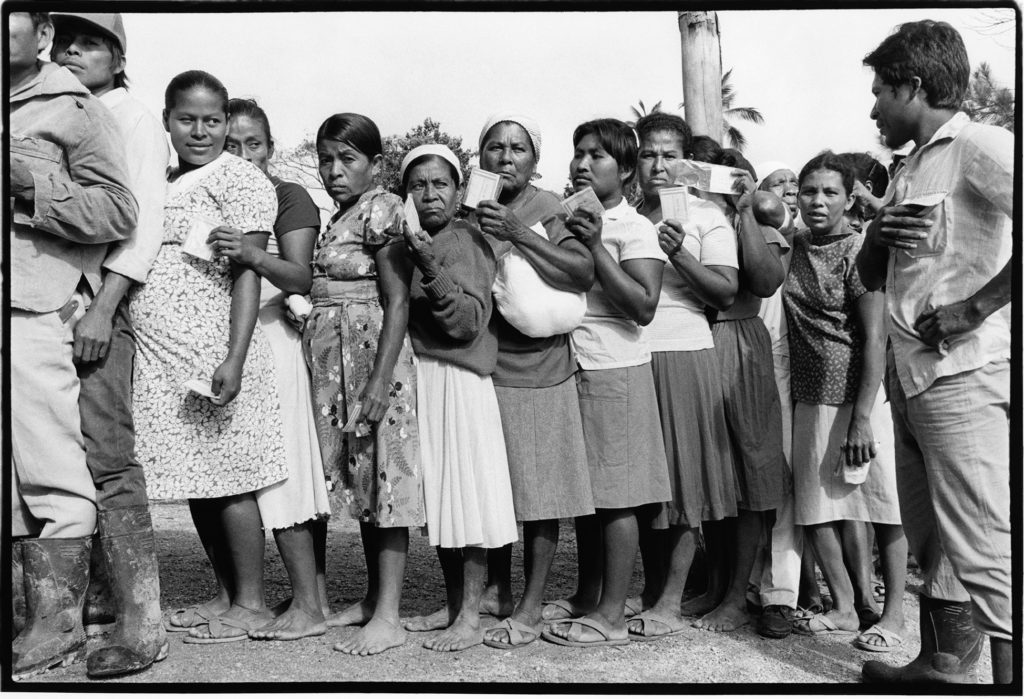

Claudia Gordillo, Celebrating the National Day of FSLN Militias in Masaya, 1984

In the aftermath of the Sandinista revolution’s triumph in 1979, the Nicaraguan photographer Claudia Gordillo Castellón began documenting her country’s urban and rural landscape. She observed rapidly transforming social and political realities during the 1980s and 1990s, producing an important body of documentary work while remaining committed to aesthetic experimentation. As a correspondent for the Sandinista daily Barricada from 1982 to 1984, she was assigned to the war photographers’ division and charged with documenting the controversial US-funded Contra war.

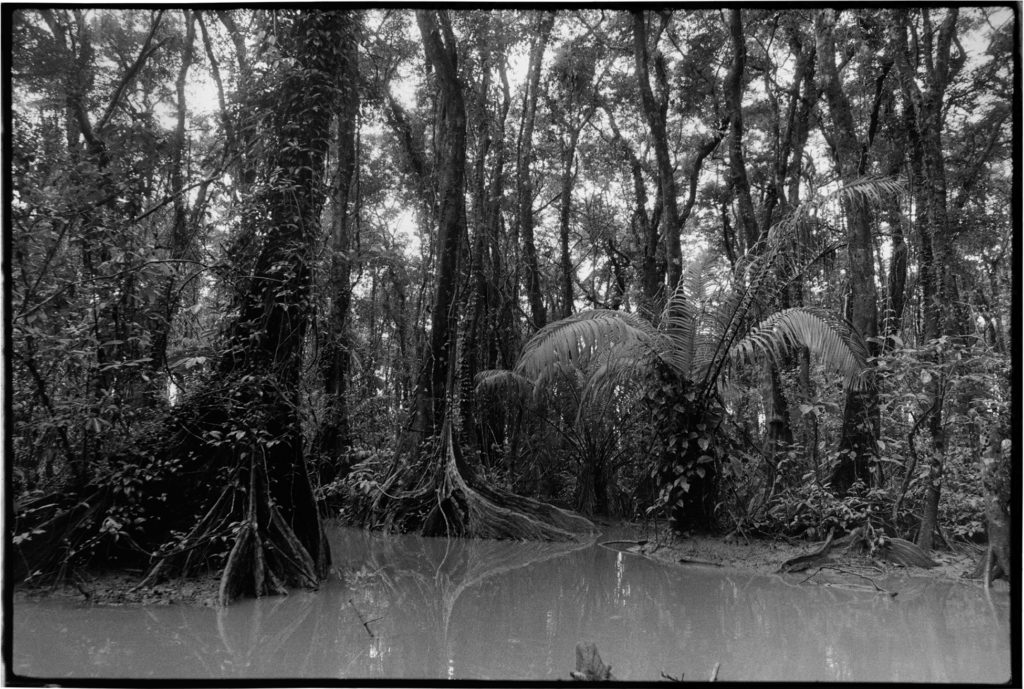

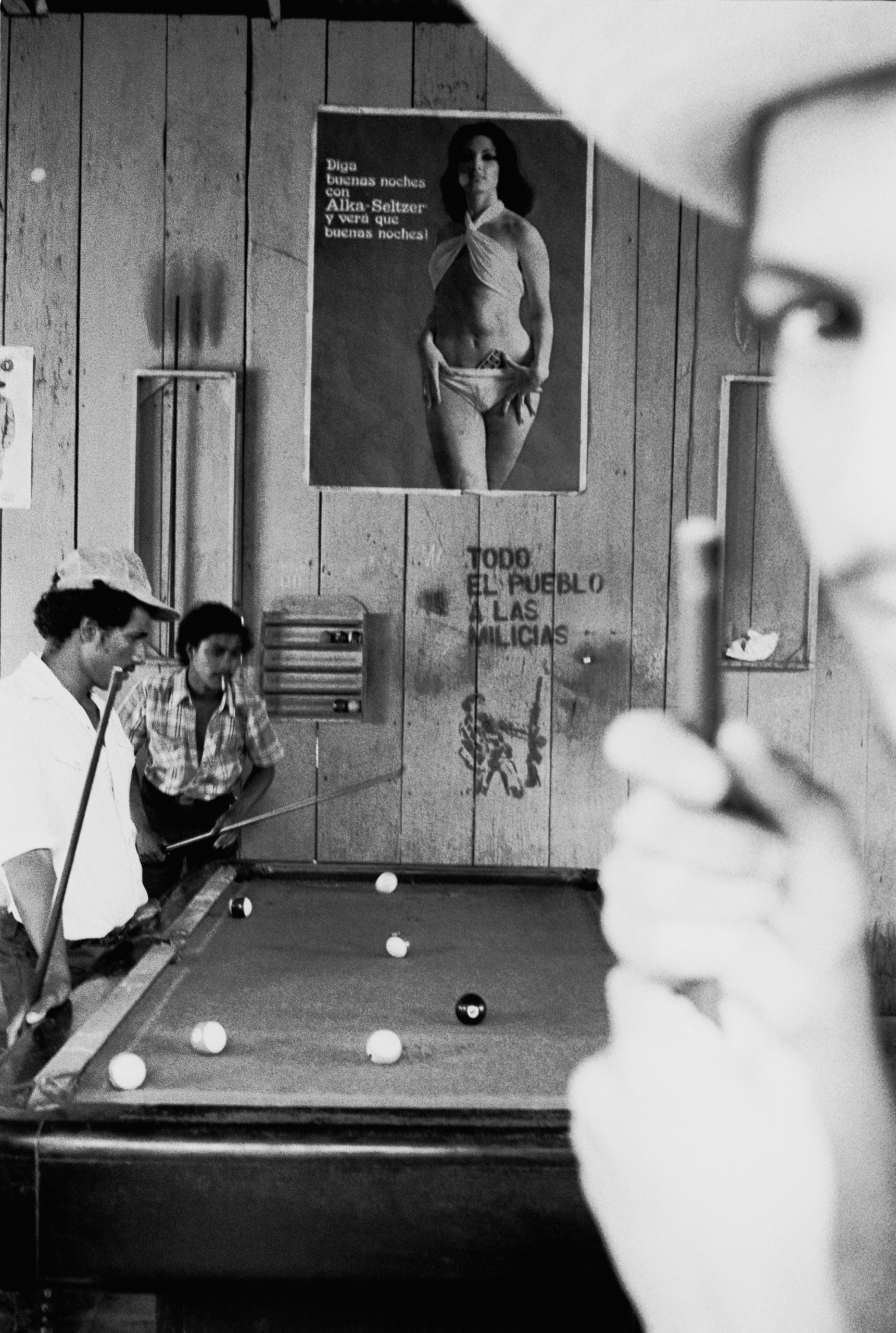

Even on the frontlines, Gordillo sought to document the context around the armed conflict, focusing on the lives of civilians caught in the cross fire. This interest in capturing the minutiae of everyday life, in the midst of dramatic and difficult historical events, characterizes her entire body of work through and through; this is ultimately what sets it apart. Whether in the barrios of Managua or the most remote regions of Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast, Gordillo sought to privilege the photographic subject, observing Nicaraguan society, habits, and daily rituals from a close yet critical distance. A persistent defender of freedom of expression, she argued that a certain degree of autonomy was necessary and that, ultimately, documentary work should not be made to serve an ideological agenda. This autonomous position nonetheless proved difficult to sustain within a context of heated ideological debate; her work still draws toward the unexpected, accidental, and even uncanny, revealing the absurdity of life, regardless of outside demands.

The Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua was one of the most photographed political movements of the late twentieth century. Photographers from around the world, including across Latin America, converged upon the small Central American nation to witness and document what was seen as an ideological conflict between post–Cuban revolutionary movements and an emerging global neoliberal regime. Gordillo documented encounters and social realities that often took place alongside the most celebrated, decisive, or so-called iconic moments of that struggle. This is a crucial distinction that has to do with decolonizing the very notion of what constitutes a political, or revolutionary, act. Inherited notions about Latin American photography maintain that a “local” documentary tradition emerged in direct response to political circumstances, which demanded taking a position. As Gordillo’s practice demonstrates, notwithstanding the photographer’s commitment to social justice, her stance was nonetheless informed by an awareness of contemporary photographic practices in conversation with Euro-American and Latin American counterparts.

I met Claudia Gordillo in 2011 in Managua, while conducting research on photography in Nicaragua. In this interview, which took place online in January 2022, we discuss the span of her career from the early 1980s to the late 1990s, and address her approach to documentary photography. Gordillo speaks about how her work responded to the pressing issues of the time, and foregrounded aesthetics while seeking to avoid cliché and ideological bias. She also reflects on her archives and how the transition from analog to digital has impacted her current perception of her body of work.

Ileana L. Selejan: At the beginning of your career, you had returned from Italy in the immediate aftermath of the triumph of the Sandinista revolution in July 1979. What was that experience like? And how did you perceive your work within that context?

Claudia Gordillo: I left Nicaragua for Europe and Italy in 1977 without a clear plan, searching for a design school. After about a year, I visited the Istituto Europeo di Design in Rome. However, as this was the best school in the field, there were no places available, except for two in the photography course. I decided to enroll immediately, so as not to lose this opportunity.

When I returned to Nicaragua after more or less two years, having completed my course, I got disappointed and began watching the outside reality through TV. I closed myself indoors, not having a sense of purpose, without a direction for my work, until I started driving around Managua in my father’s car. I was observing the changes left by the war and the earthquake that had destroyed our city. I repeated these outings many times and discovered thus the [ruins of the old] cathedral where I made a series of photographs, which later ended up stirring an entire debate about the role of the arts in the revolution.

Selejan: Could you talk about the controversy surrounding your first exhibition in Managua, where you showed that series from the old cathedral? I know it was a very difficult moment in your career.

Gordillo: The exhibition of the cathedral series created a debate against freedom of expression. Because, according to one of the nine Sandinista commanders [from the National Directorate] who gave an interview at the time, the arts were to serve the revolution, nothing else.

Selejan: At the start of the 1980s, you worked for the newspaper Barricada, which was the official publication of the FSLN [Sandinista National Liberation Front]. How would you describe the work environment at the newspaper? Was there great interest in photographic reportage?

Gordillo: Yes, there was interest in reportage, however, only if favorable to the party. This was, after all, the official outlet for the FSLN.

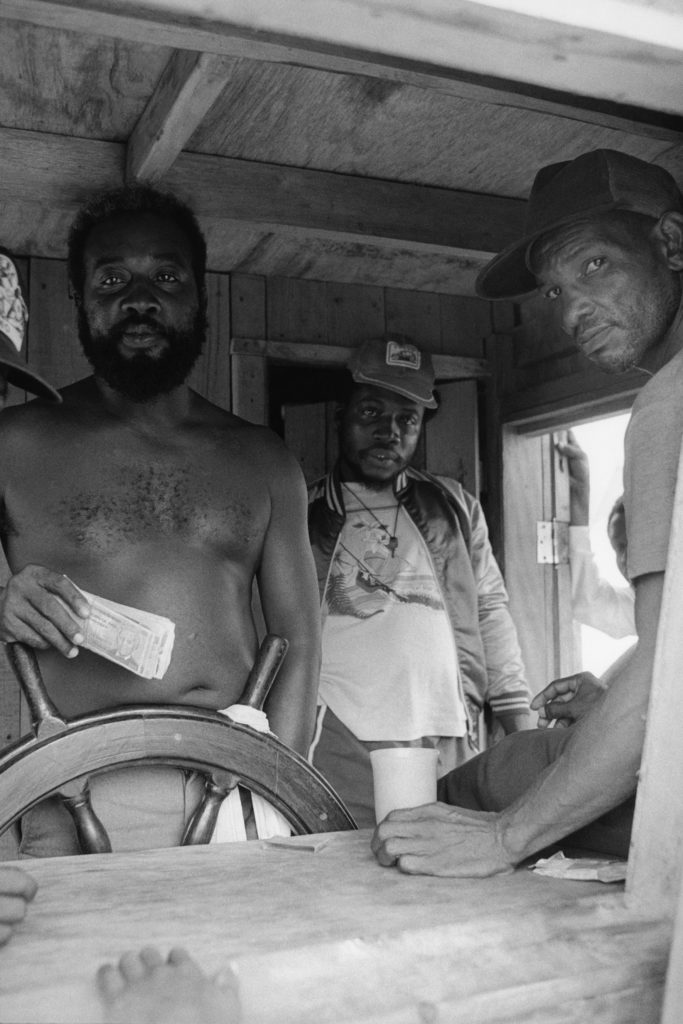

Back then, there was hope that the revolution could be defended against attacks from the Contra, and the type of photography Barricada commissioned reflected this triumphalist stance with regard to the war. When I got to the San Juan River [in the south of Nicaragua] on an assignment, volunteer battalions were still present in the barracks at San Carlos. We’re talking about 1983, a high point in the Contra war. I felt very good there, away from directives and with more freedom of movement. I ended up staying for around three months, and every now and then, they would send me [collaborating] journalists, film, and money. Since they were most interested in photographs of the war, I decided to move to the headquarters in the area, with permission from the regional army chief. This was my best assignment as a correspondent, and Barricada liked it.

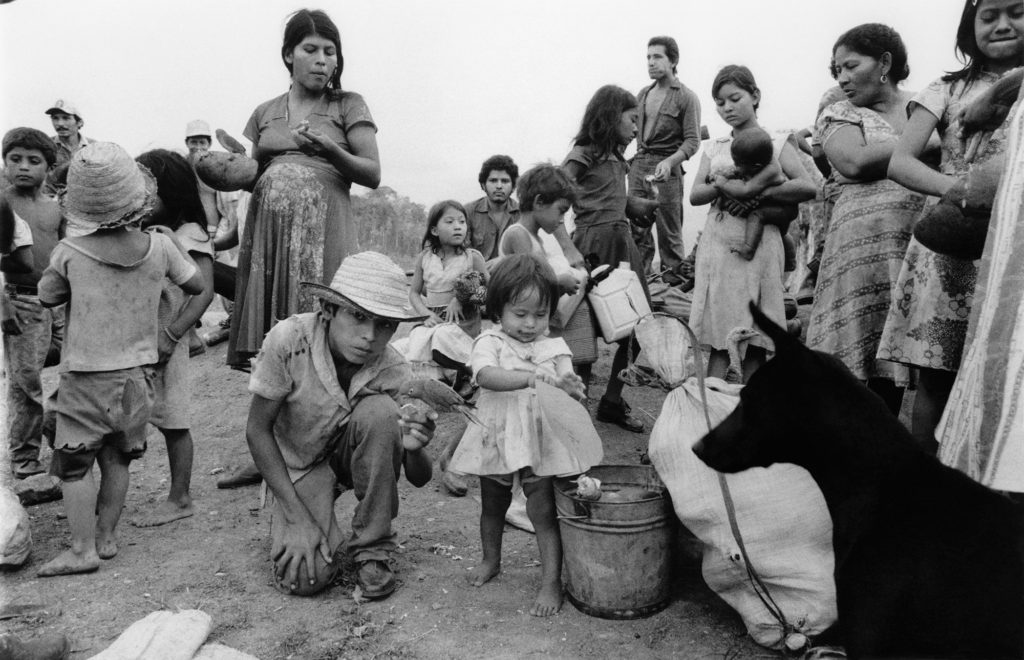

Selejan: Several of your trips to the war zone led to you witnessing dramatic events, such as the relocation of local communities. Were those images controversial at the time? I see them as contradicting the official narrative of the revolution.

Gordillo: I only witnessed relocations in the area around the San Juan River, precisely where previous errors in such campaigns were taken into account. That is to say, they allowed the transfer of animals and crops with the help of Sandinista militias. It was different, even if mandatory, because they helped people to evacuate. I was myself part of the well-seasoned brigade of militiamen, peasants, and militants that carried out the operation. This was a unique experience, since I was living at the San Carlos headquarters, sleeping in a hammock in front of the San Juan River. My story was published, with Barricada selecting the photographs.

Selejan: Some of the work from this period you returned to later, reconsidered as the series Fragmentos de una revolución [Fragments of a revolution]. What does a retrospective view add to your reading of the work? And how has that changed throughout the almost four decades since?

Gordillo: Learning to scan negatives was what changed my perspective. I was always looking at my contact sheets, marking the shots to be printed. Because I was working, I never really had enough time to do proper lab work. For instance, the San Juan River story took up many film rolls and contained many frames that I had actually never seen. It was only when I started to scan them that I could properly appreciate many of the negatives that were stored away for over thirty years. My work focused on the people, rather than on politics and leaders.

Even with Barricada, I went on several assignments where, say, one of the commanders would give the main speech, but even then, it wasn’t the most interesting part for me. I wasn’t that inspired, beyond my duty toward the newspaper and managing to get the images they requested. Neither did I have any sentimental attachment to anyone, because I thought that would negatively impact my observation. I needed to have freedom of thought—I was always very clear about that. It was always very present in my mind. As the years passed, I realized this was the most adequate stance, given my status as a reporter or photographer. And I was dedicated to searching for images that somewhat questioned the system.

Selejan: The 1980s were a tumultuous decade in the history of Nicaragua, to say the least. You documented the sociocultural changes taking place with great interest, yet chose to focus on everyday life instead of heroic deeds and history with a capital H, always with an eye for the extraordinary in the ordinary. This strikes me as greatly contrasting to the work of other photographers who were working in the country at the time, including those coming from abroad. Is this the case?

Gordillo: What happened was that I was living here, and so the political discourses sounded hollow to me. The Sandinistas talked a lot about the “achievements of the revolution,” while we were living right in the middle of this tremendous poverty, with shortages of all kinds. Many of those coming from abroad believed this discourse. Not all, it must be said. But I wasn’t paying much attention to this. I wanted to get to know, and to understand, Nicaragua from the perspective of the [popular] markets, how people lived here. I wanted to understand how traditions functioned, their logic and origins, things that were not [necessarily] related to contemporary politics. My intention was to continue discovering those elements I identified with.

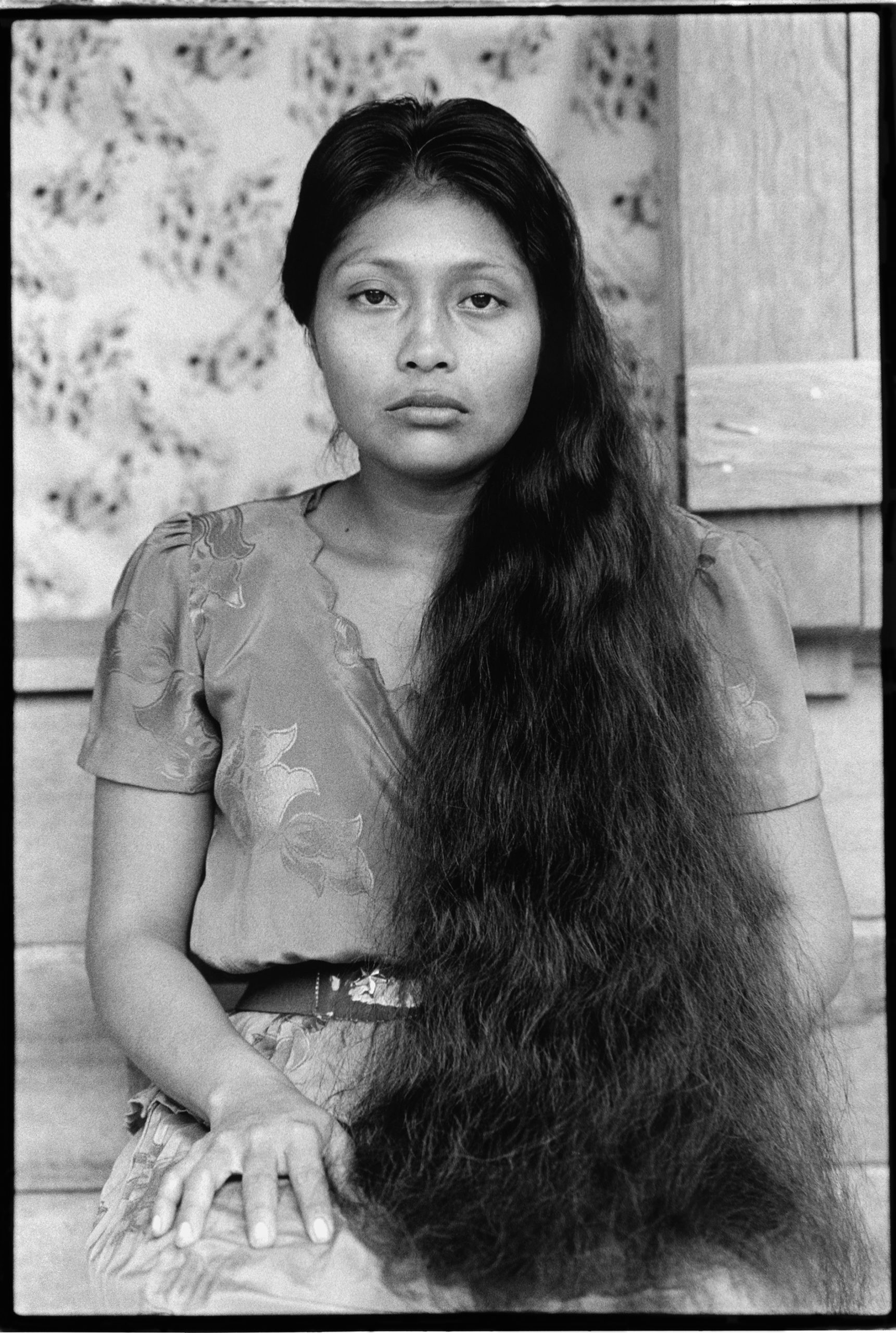

Selejan: After leaving Barricada, quite early on you started working with CIDCA [Center for Research and Documentation of the Atlantic Coast] on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua. At the time, the FSLN government was seeking to expand its influence in that region, while being quite ignorant of local dynamics among the primarily Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities. A significant body of work ensued from that experience. How do you perceive it now, several decades later?

Gordillo: The outcome of my work on the Caribbean coast is quite anthropological, without a doubt due to the influence of [anthropologist] Galio Gurdián, who was then director of CIDCA, and who set out to research local cultures, ethnic groups, and their traditions. I thought it was interesting to photograph life in the Caribbean, approaching significant details, although you couldn’t speak about other subjects—it was already a challenge to do so without falling into the usual clichés. Also, there was not enough information about the political issues between the Pacific and the Caribbean. That was a confidential topic. Still, at CIDCA we had a lot of freedom in pursuing our work, even if within certain limits.

Selejan: In the early 2000s, you published the book Estampas del Caribe nicaragüense: Portraits of the Nicaraguan Caribbean with filmmaker and photographer María José Alvarez. It brought together documentary work that you produced over a significant time frame while traveling across vast Indigenous territories. The Caribbean coast is often stereotyped, perceived as exotic and extremely remote, peripheral to most of what goes on in the rest of Nicaragua. By contrast, your work portrays a highly relatable, albeit singular world, one that lives according to its own rules and logic. What was it like to make that work, and how do you perceive it now?

Gordillo: Some exoticism pervades in at least some of the photographs from the Caribbean. It was hard to avoid, given the monumental beauty of the region. Galio Gurdián always gave me a lot of license in my work to document the coast, despite his ties to the FSLN. CIDCA’s commissions were always concerned with the different ethnic groups, their ways of life, fishing, and all that concerned the organization of the various communities. A bit of politics slipped in there, although discreetly.

I can see now that I stuck to the rules, an outcome that is visible in some of the photographs. You needed a special permit to go into the Caribbean region, a type of passport, nationals and foreigners alike, which was why I always thought there were serious long-term issues that were deliberately hidden. CIDCA’s task was to generate historical documentation of the region. A lot of things were achieved, such as the publication of the first grammar of the Rama language, something that had never been done before.

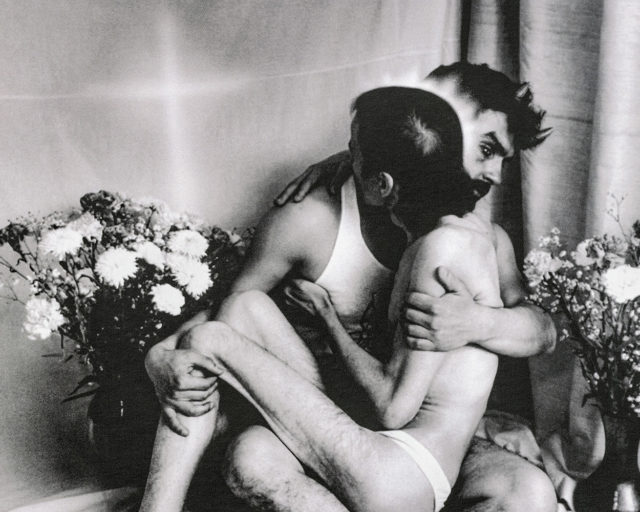

Selejan: Here, I’d like to return to a project that you started even earlier in your career, after returning to Nicaragua, Memoria Oculta de Mestizajes [The hidden memory of mestizajes]. I feel like you approached this subject from an anthropological angle, something that ultimately characterizes the majority of your work. Yet I would say that your analytical perspective shines forth powerfully. I remember many years ago, you mentioned how your photography was a means to learn about Nicaraguan identities, what made the country tick. Is that part of what’s happening?

Gordillo: Yes, it’s part of the same. Identities are important, especially in a multiethnic and pluricultural country.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Selejan: You have spent over twenty years working as a curator, conservator, and archivist caring for the photography collection at the IHNCA [Institute of History of Nicaragua and Central America] in Managua. We are both tragically aware of the extent to which neglect and lack of funding has led to the destruction of a lot of the photographic heritage in the country. You have been looking at those fascinating materials while going through your own archive. How has this process of revision impacted the way you look at your own work?

Gordillo: Archives are always a fascinating resource for books, documents, and historical images. With time, I learned a lot about the conservation and proper handling of such materials. Digital technology taught me to look at my work in ways I never considered before. In the analog era, you had to first print out a contact sheet, and then print a [selected] frame as a small or medium-sized print, before finally choosing a negative. Learning to scan film was a great discovery for me, seeing my photographs on the screen, many of which I had never printed before and, therefore, wasn’t familiar with. I was very curious to see certain photographs, and the digital allowed me to get to know my own archive better.