In Performance

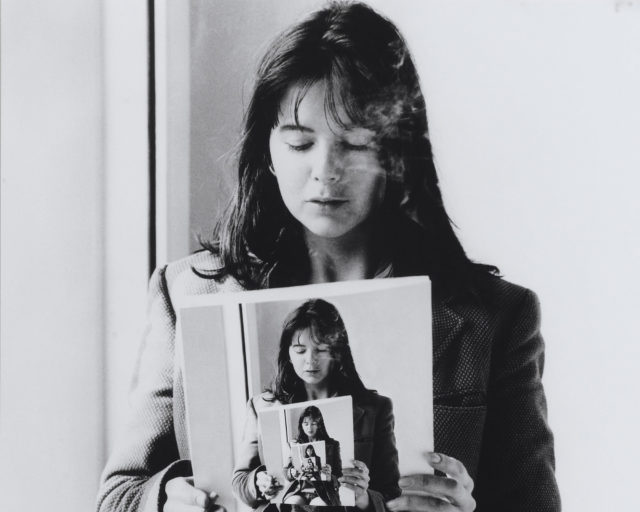

Gillian Wearing, Self Portrait as my Sister Jane Wearing from Album, 2003

We are all performers. Actors and con men make it their profession; the rest of us just make it our lives, preparing, as T.S. Eliot said, “a face to meet the faces that you meet.” Photographers first formed a bond with performance in 1839 when Hippolyte Bayard, angry that his role in the medium’s invention had been ignored, photographed himself as a drowned suicide victim—and included a note he’d written after his death. Notable performances followed: the Countess Castiglione as four hundred selves, Marcel Duchamp as his feminine alter ego, Claude Cahun defining the many facets of lesbianism, Cindy Sherman as a galaxy of others.

IN CHARACTER: Artists’ Role Play in Photography and Video gathered work by Kalup Linzy, Yasumasa Morimura, Laurel Nakadate, Tomoko Sawada, Cindy Sherman, Lorna Simpson, and Gillian Wearing, all performing by themselves for their own cameras—a timely recognition of the major place not only of performance in today’s photographic media but also of artists themselves as the performers.

The exhibition introduced two little-known series made by Sherman in 1976: Murder Mystery People and Bus Riders. Neither of these has the assurance or inventiveness of the Film Stills (1977–1980), but they make clear where she was headed before and just after graduation from college. Playing all the stock characters of Hollywood murder films, she suggested that movies have embedded these, and our responses to them, in our expectations. Playing bus riders, she explored a range of self-presentation among ordinary people. Her next project, the Film Stills, would combine the two, with nods to media critique and ideas from the feminist and gender-based movements.

The desire to try out being someone else begins very early, when little girls play mommy and little boys play grown-up cowboys. Gillian Wearing, a grown-up artist quite aware that families are the first role models and, of course, integral components of ourselves, made images of herself as her family members, including her mother as a young woman, her father, and her uncle. Well, not exactly images of herself: the likenesses were masks she made and wore: family and photographer both at one remove, artificial identities reconstructed and preserved in arresting portraits.

Everyone has a face to put on for a photograph, but seldom is that such a literal matter.

The popular notion that identity of all sorts is fluid—on the U.S. census, some people write in “other” for race—has been greatly magnified by digitization. Tomoko Sawada changes her face, hair, and expression repeatedly to become every student in class graduation pictures. This is cloning with a variation and a vengeance, an obscure desire to be not one in a crowd but the crowd itself. Sawada demonstrates the ease with which you can now believably put yourself in others’ shoes, like the middle-age man who passes himself off as a teenager on social networks, and the cartoon dog that memorably told a canine friend, “On the internet, nobody knows I’m a dog.”

Art is of and about its times. Performance art, which goes back at least to the Futurists in the early twentieth century, stepped into the spotlight in the 1960s when artists were expanding art’s territory, and even its definition, with land art in places remote from museums, sculpture that utilized nontraditional materials like rubber tires and stuffed birds, and paintings that appended sculptures and tools. Performance went outside theater and its traditions as well, and was often politicized (engaging feminist, gender, and racial issues) and often rebelled against dominant structures.

Tomoko Sawada, Omiai (#16), 2001

Contemporary photographers like those at the Addison frequently reflect the gender, ethnic, and other identity issues that arise with widening recognition and acceptance (and ongoing mistrust) of any “other” in our multicultural, globally intertwined, and rapidly changing era. Lorna Simpson reenacts found photographs of African Americans, playing both male and female roles and suggesting that the past is always being replayed, like an old CD. Kalup Linzy’s videos go in and out of drag as they take a leaf from soap operas and minstrel plays—he is African-American—plus several swipes at reality, including obviously altered voices. Yasumasa Morimura, whose photographs have long played fast and loose with gender and race (and iconic paintings and photographs), does a video rendition of himself as Chaplin/Hitler in The Great Dictator, poking fun at der Fuhrer. A Japanese performer playing a Caucasian one—and in a sense parodying a parody—Morimura takes off on the weak spot in Chaplin’s film, but Charlie still comes out ahead.

Laurel Nakadate’s video Oops!, 2000, situates male-female relations in an inability to connect. She asked male strangers if they’d like to make a work of art with her, then went to their homes and danced with them to Britney Spears’s “Oops!… I Did It Again.” The men, all middle-aged, unprepossessing at best, and apparently loners, dance tentatively or awkwardly; one simply stands there impassively. The question of male control hovers here, but Nakadate seems to have the upper hand, being young, attractive, and sexy—and in possession of the camera. Still, this is performance as risk: she could have been but never felt in danger; the men’s self-images, on the other hand, must have been, raising yet another question about photography and the nature of identity.

Laurel Nakadate, Lucky Tiger #80, 2009

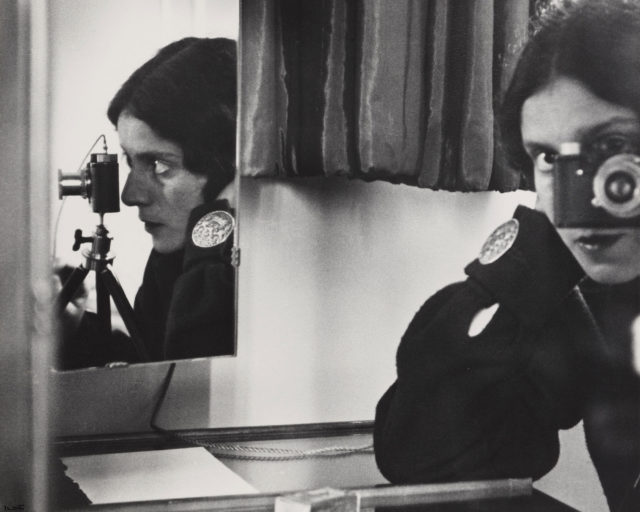

The Addison cleverly dedicated its second space to Making a Presence: F. Holland Day in Artistic Photography. Day, a rival of Stieglitz, was endlessly photographed by his friends and himself, and was always performing to one degree or another—whether in costume or not. In his most famous, and controversial, performance, Day photographed himself in the role of Christ on the cross uttering the seven last words. In order to play this highly charged role, Day strenuously outdid those who came later: he recreated himself physically before doing so photographically, via a rigorous weight-loss program to approximate his idea of a gaunt Jesus plus a refusal to cut his hair or shave until both hair and beard reached biblical lengths.

It is revealing that the medium that for more than a century was hailed as irrefutably realistic should be represented from the beginning by a self-portrait performance (Bayard’s) that announced it was a pretense. Oscar Rejlander, the Countess Castiglione, and myriad others continued to playact and contrive games long before the current crop of performing photographers. Humans may not be entirely sapiens but we are certainly ludens—players. The cultural historian Johan Huizinga, who declared play an essential part of culture, wrote, “Play cannot be denied. You can deny, if you like, nearly all abstractions: justice, beauty, truth, goodness, mind, God. You can deny seriousness, but not play.” We relish fiction and the thin dividing line between reality and illusion; the play’s the thing at the theater or cinema, where we suspend our disbelief without entirely relinquishing it.

And everyone’s imagination plays another self at some point: younger, better-looking, more skilled, whatever. Photographers who perform scripts imbued with cultural politics are actors pretending another self they might hope they’d never become. In any case, it’s a self converted into a message bearer, a commentator, the embodiment of an idea, the principal player in a role-playing game. After all, art is always one kind of transformation or another, and artists’ work is very serious play.

In Character: Artists’ Role Play In Photography and Video, cocurated by Allison N. Kammerer and Michelle Lamunière, was presented at the Addison Gallery in Andover, Mass., in collaboration with the Harvard Art Museums, April 14–July 31, 2012. Making a Presence: F. Holland Day in Artistic Photography, guest curated by Trevor Fairbrother, was also presented at the Addison Gallery, March 27–July 31.