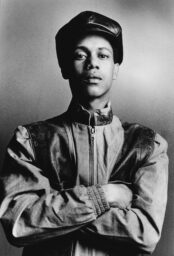

Introducing: Lindokuhle Sobekwa

The day his older sister Ziyanda disappeared, Lindokuhle Sobekwa was hit by a car. The two were walking together along a road in the Johannesburg suburb of Thokoza when Ziyanda began to chase the seven-year-old Sobekwa. Out of fear, he began to run, and then he was hit. Above him, he recalled before blacking out, was the blurry silhouette of a woman or girl. His sister vanished in the ensuing scramble, with no word as to why. “She was in a period of being a very secretive person,” Sobekwa remembers. She was thirteen years old.

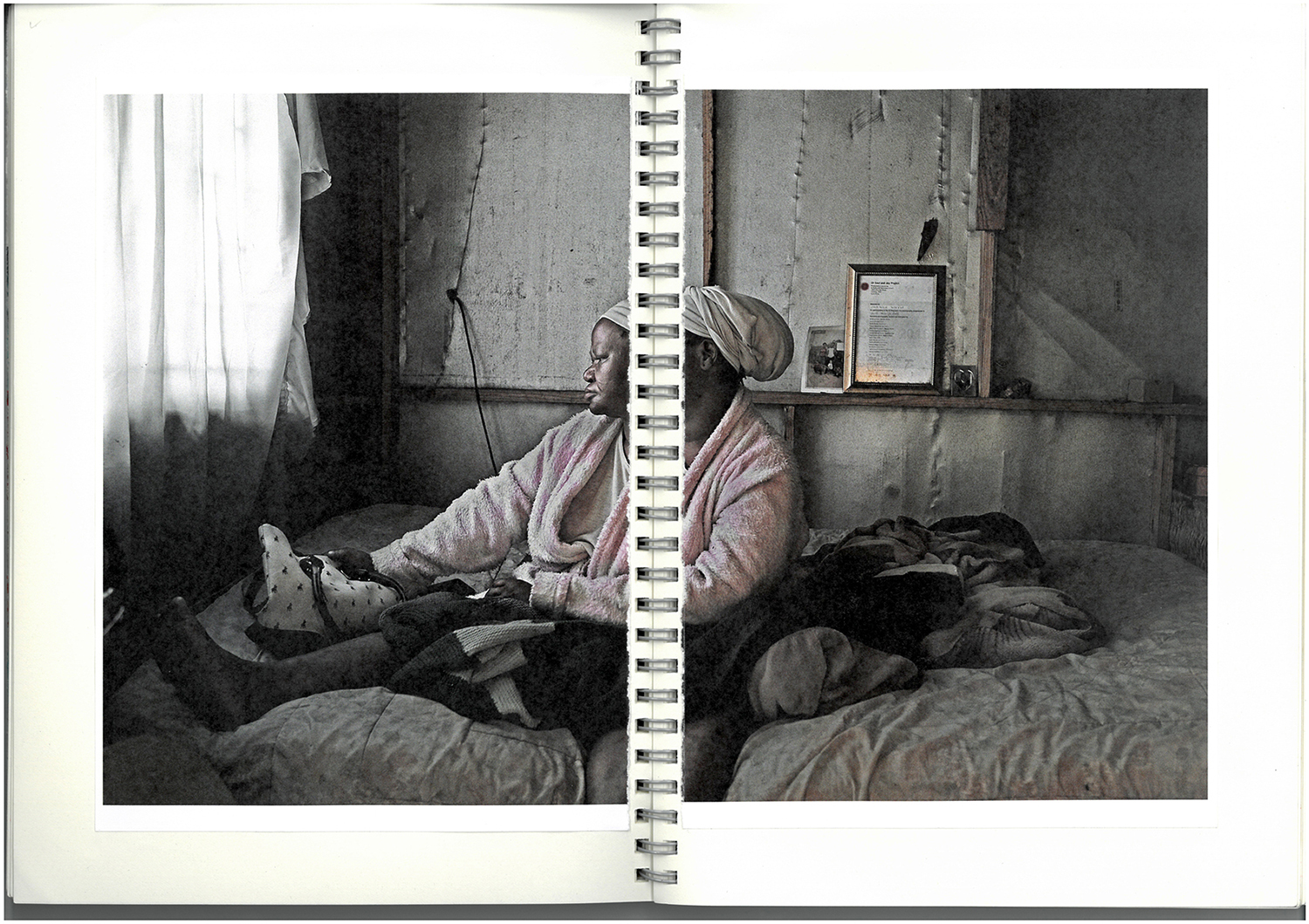

Sobekwa would not see Ziyanda again for a dozen years. Then one day, he returned from school, and Ziyanda was at home. She was reunited with the family for a couple of weeks. At the time, in 2014, Sobekwa was coming into his own as a photographer. He was in his final year of high school and working under the mentorship of Magnum photographer Bieke Depoorter and filmmaker Cyprien Clément-Delmas through the Of Soul and Joy project, an artistic initiative based in Thokoza. He remembers walking into Ziyanda’s room one day; in that moment, he saw his favorite would-be portrait of his sister: “She was lying in bed, there was a beautiful light. She said, ‘If you take a photo, I’m going to kill you.’ A few days after that, she passed away.”

Sobekwa did not plan to make a series about his sister. In 2016, he was deep into his first photographic series, Nyaope, which chronicles the cycle of drug abuse that has afflicted Thokoza and takes its name from the heroin-based substance at the center of the crisis. In Nyaope, Sobekwa’s subjects are his peers, many of them childhood friends; he captures their makeshift, communal homes, rituals of abuse, and often frayed, sometimes fearful expressions with a documentarian’s precision, peppered with tenderness.

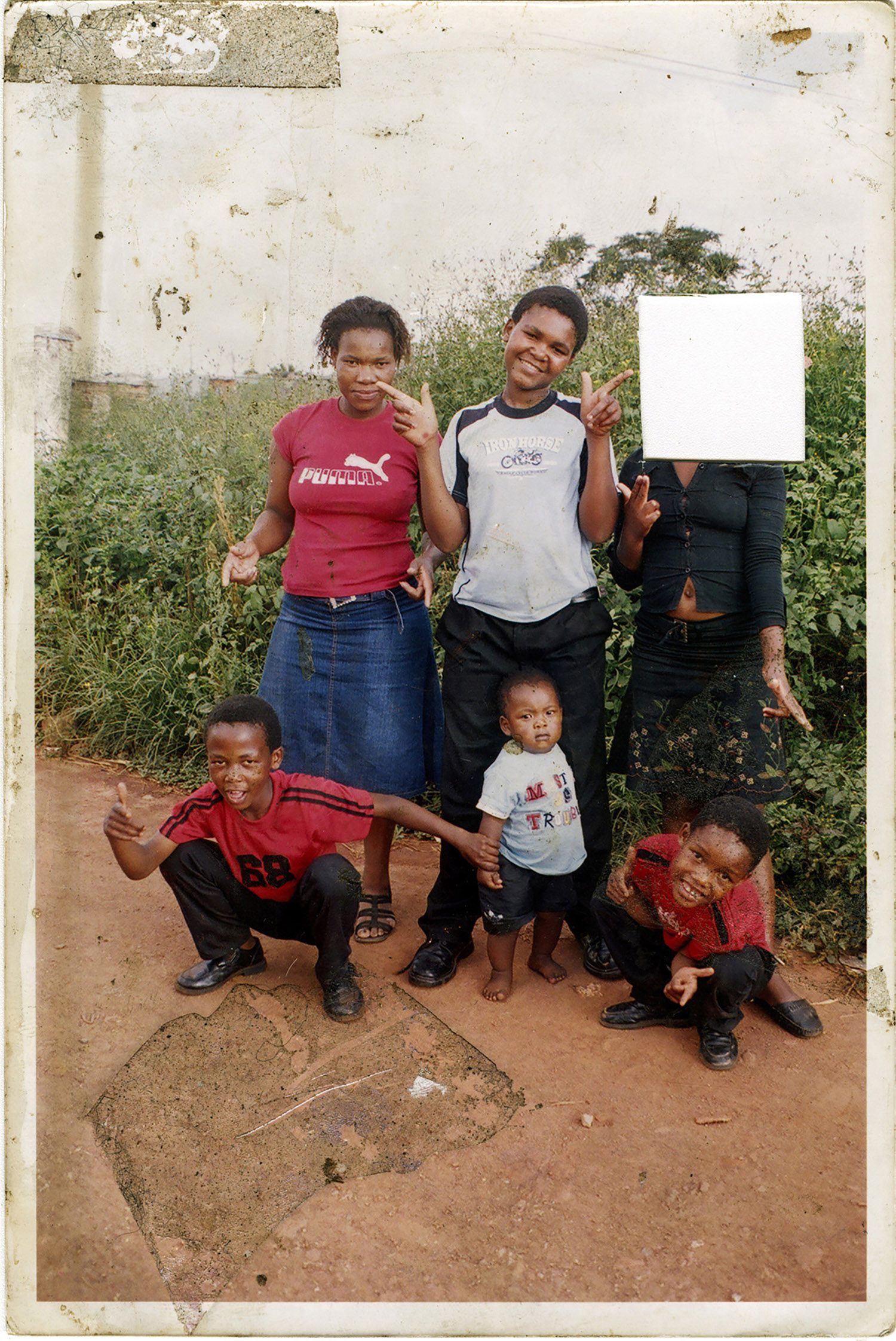

While photographing the surrogate family structures of nyaope users, Sobekwa came across a portrait of his own family, a photograph he had not seen in years. In it, Sobekwa is a young boy, alongside five family members. Ziyanda is there. She’s wearing a green cardigan and a matching skirt with a delicate floral pattern. The skirt disappears into the green shrubbery that frames the group. Her face has been completely cut out, leaving a sharp white square.

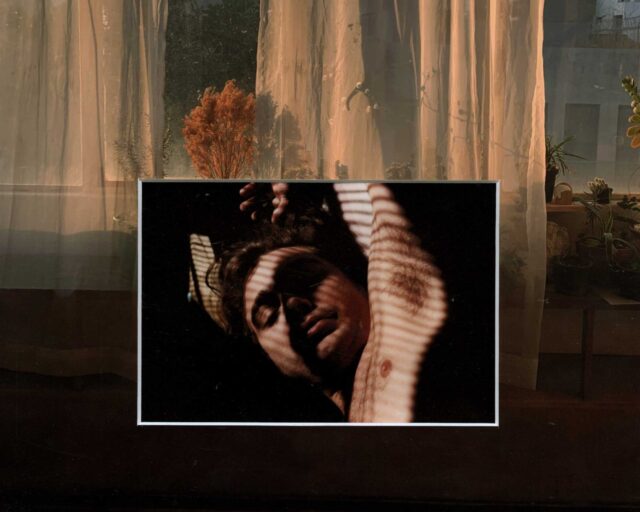

The photograph prodded at Sobekwa. His sister had become a highly taboo subject in the family, with no one willing to discuss her, neither while she was missing nor after she reappeared. Sobekwa needed a map to trace her disappearance, her passing, and to fill in her missing years. He began to craft a photo diary for himself, gathering snapshots of the places she lingered—like the clothesline in their backyard, where her garments were still hanging.

Disappearances are not rare in South Africa, Sobekwa says. Most Black South African families are familiar with the trauma of disappearances, which date back to the late 1980s and early ’90s, the height of the apartheid crisis. During this time, an ethnopolitical war between two rival parties, the African National Congress (ANC) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), suffused the townships with panic, as residents along the factional line were routinely vanished by violence. In Sobekwa’s family, the cycle began with his grandfather, who was the first of the line to come to Johannesburg, in the 1960s. He never returned to the countryside; his fate is still unknown.

In 2017, the Magnum Foundation named Sobekwa a Photography and Social Justice Fellow. Suddenly, he had the resources to expand his search for his sister and develop his personal journal into a full-fledged series, I carry Her photo with Me (2017–ongoing).

“I had my own unanswered questions, maybe guilt of some sort,” says Sobekwa. “I felt the need to go into these spaces and make the camera my excuse. I realized that going alone, it would be difficult.” With his camera in hand, he slipped once more into the role of documentarian.

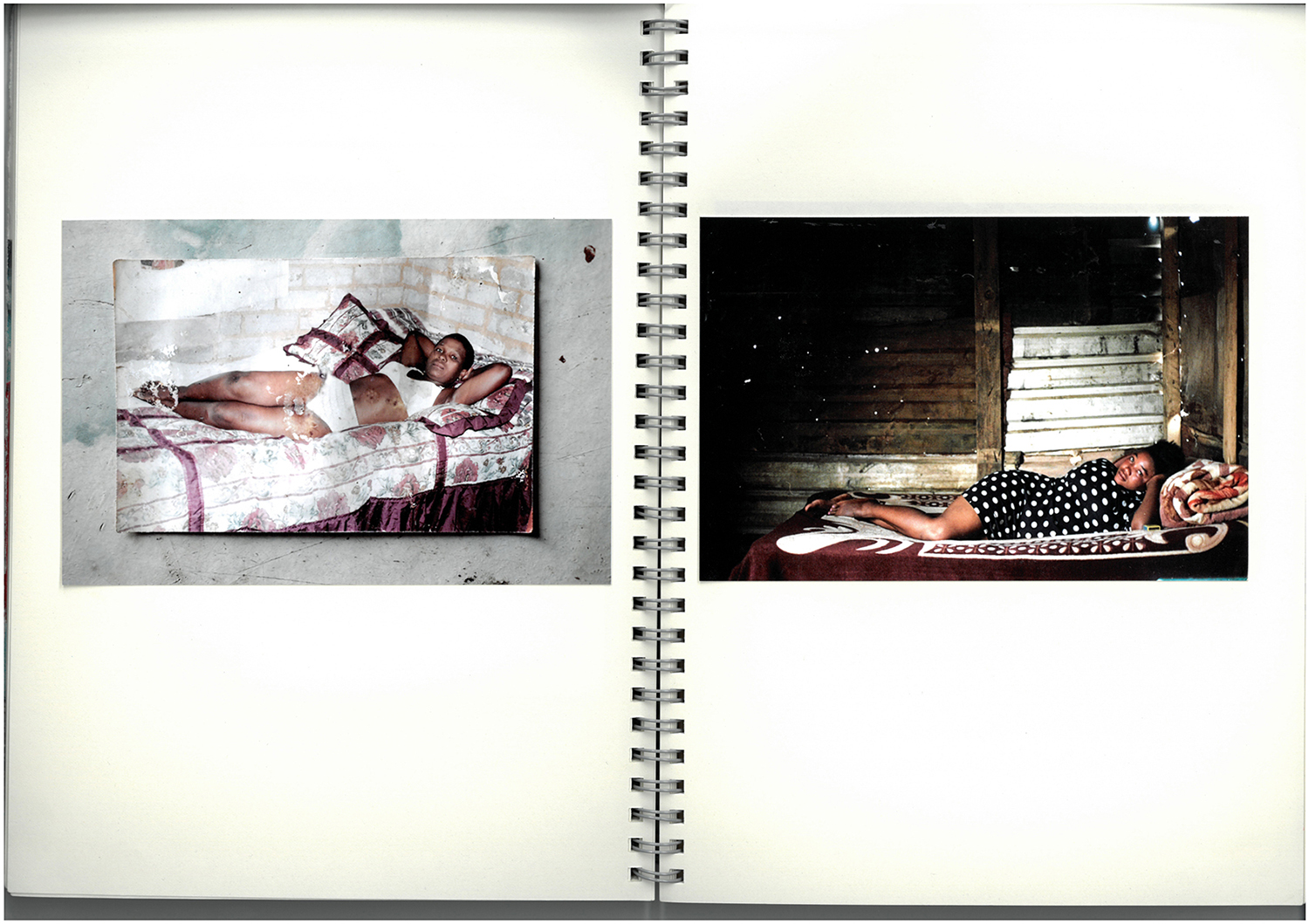

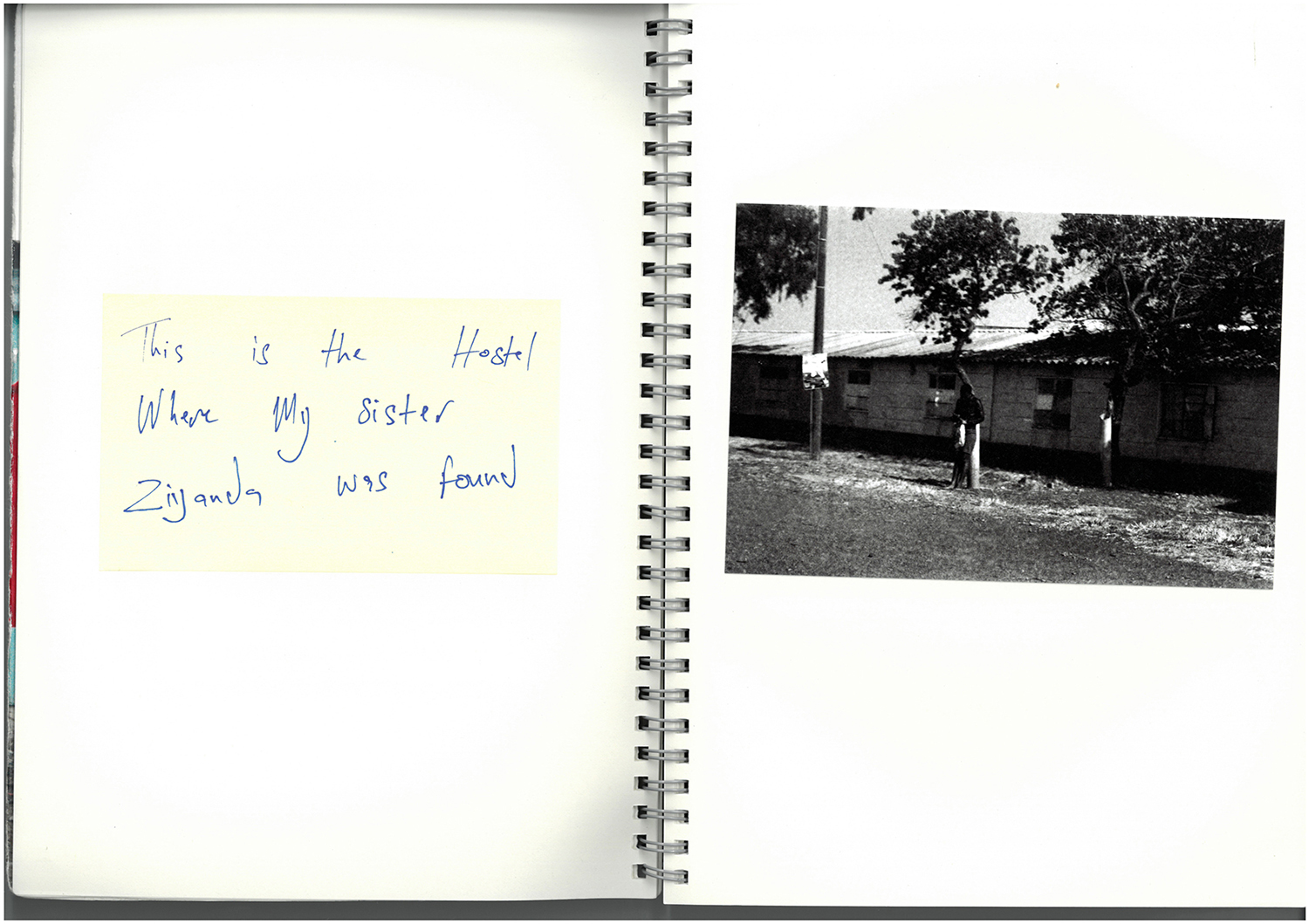

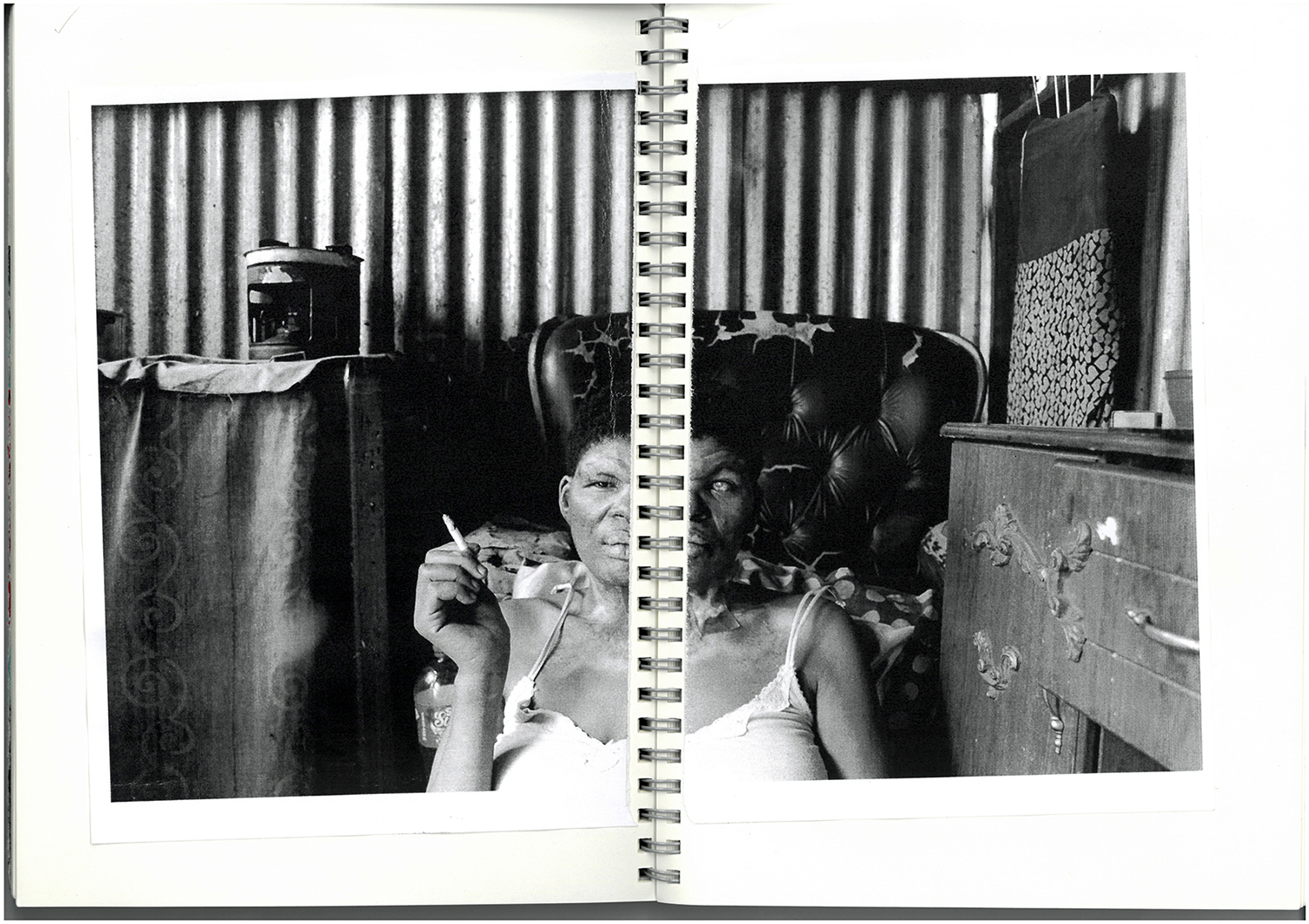

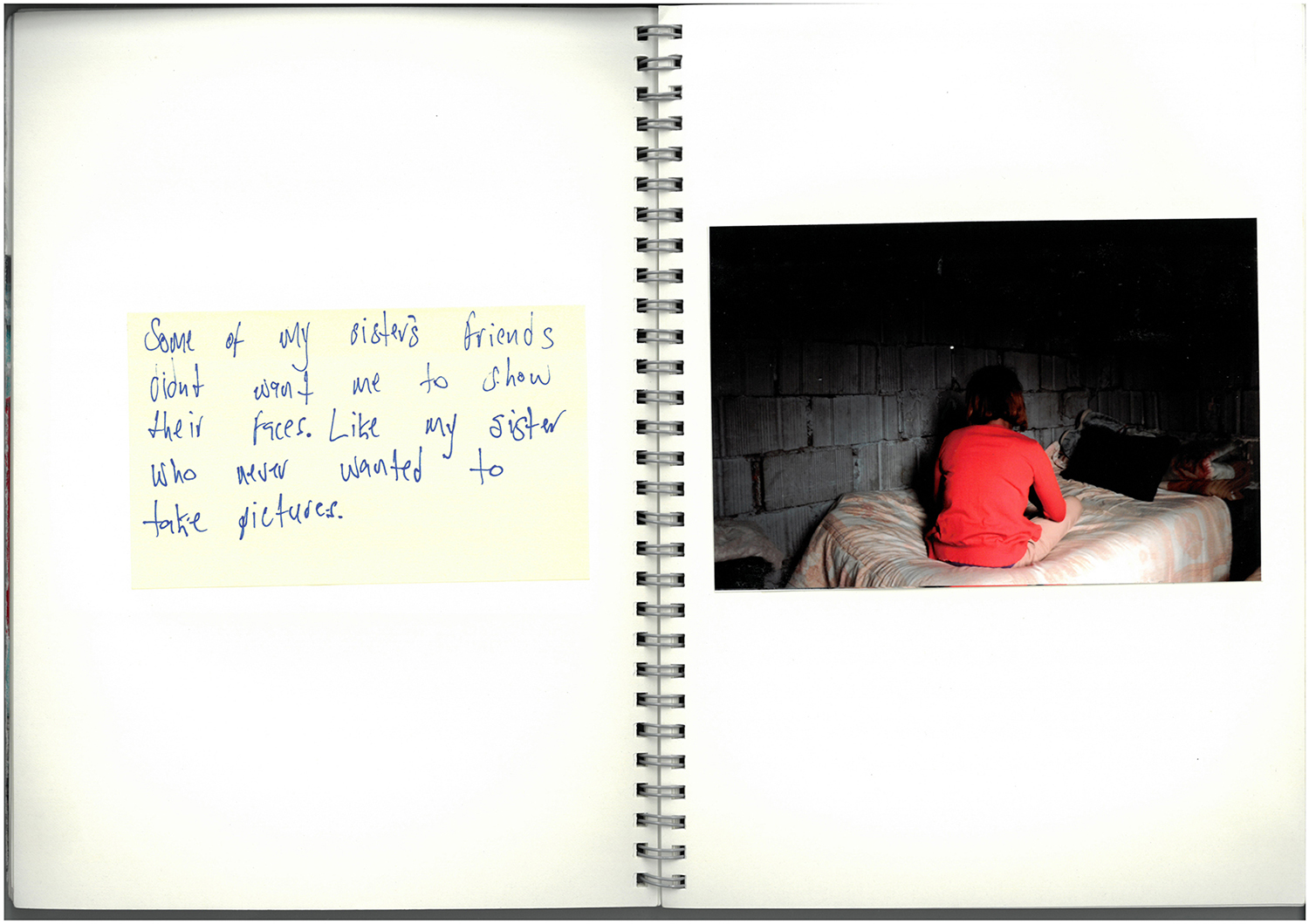

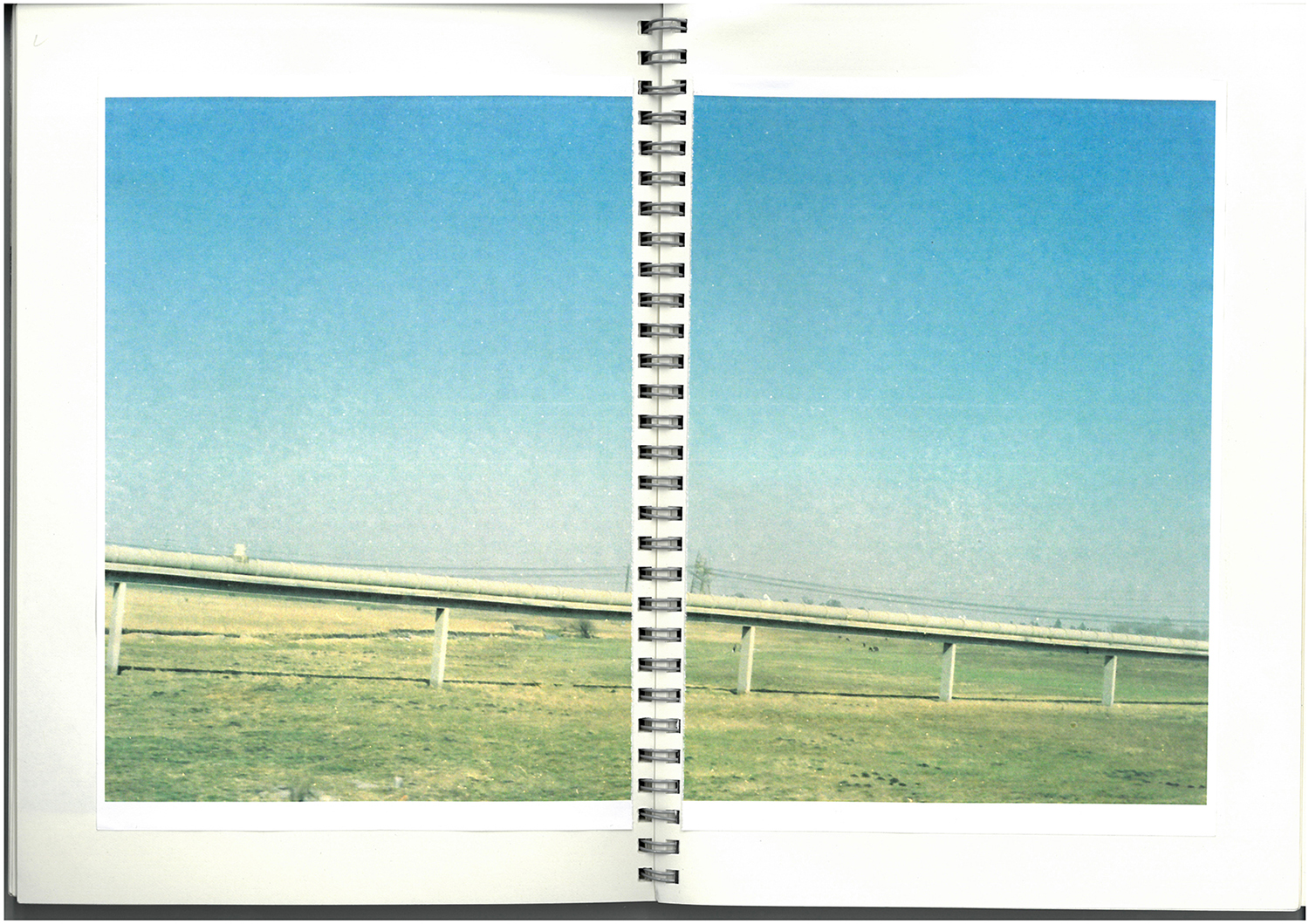

His mother had been the one to find Ziyanda back in 2014, at a men’s-only hostel called Shaye Aze Afe, and so Sobekwa started there. At Shaye Aze Afe, he took photos of the landscape, the shaded exterior of the hostel. He found a cousin who knew someone who knew someone else; they lead him to a second hostel, where tenants had been friends with Ziyanda. He took portraits of these women. He took portraits of strangers, whom he imagined as stand-ins to fill out Ziyanda’s community. In his notebook, he wrote: “Some of my sister’s friends didn’t want me to show their faces. Like my sister who never wanted to take pictures.”

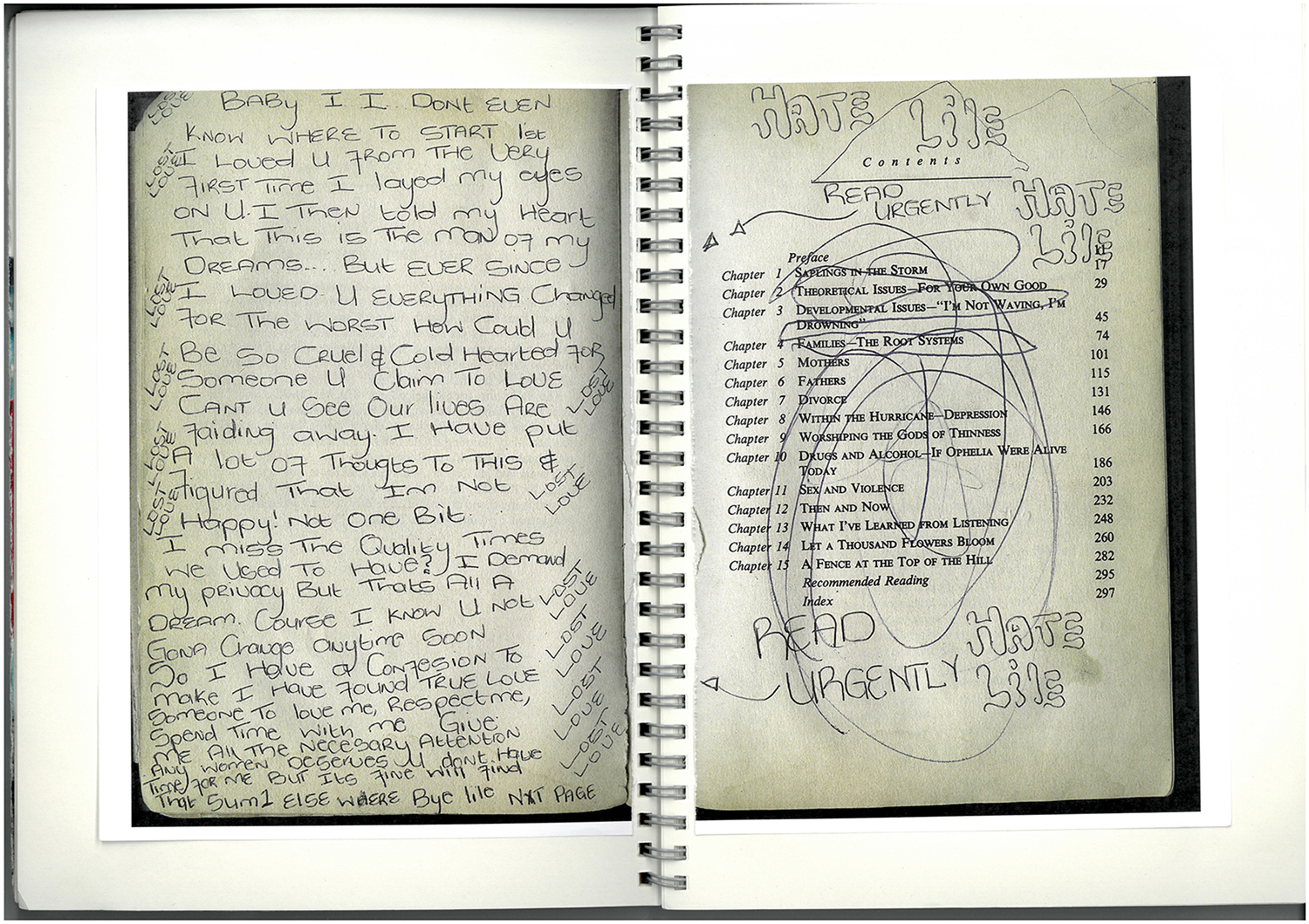

By contrast, other subjects pose on beds and stare straight into the camera with enigmatic expressions—outfitted in a polka dot dress, or a white brassiere-and-briefs set. One tenant scrawled song lyrics over the table of contents of Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls, and these pages rest between Sobekwa’s portraits. Alongside “Chapter 8: Within the Hurricane––Depression” and “Chapter 11: Sex and Violence” are slanted, bubbled words like “HATE” and “READ URGENTLY” and “I Demand My Privacy But That’s All A Dream.”

Cape Town–based writer Sean O’Toole says that Sobekwa shares an “obvious kinship” with Santu Mofokeng, the South African photographer known for his striking black-and-white photo essays on township life. Both artists offer examinations of race, class, and segregation that are as rigorously journalistic as they are rife with the intimacy of lived experience. For Sobekwa, the tactile, scrapbook format is essential to the project, and the photographs are as much a public record as they are the artifacts of a private myth. “Lindo’s practice is, in some ways, discontinuous with the performative leanings of much recent photography I’m seeing made here in South Africa,” O’Toole says.

Photographer Mikhael Subotzky calls Sobekwa—who became a Magnum Photos nominee in 2018—“preternaturally talented,” and he admires in the young artist’s work “a vision and a sensitivity that is already uniquely his.”

Sobekwa and his brother recently journeyed to the countryside, where his grandmother still lives, and where Ziyanda spent her childhood and is now buried. Sobekwa is continuing the series, hoping to unlock the secret of his sister’s disappearance by photographing this other landscape of her life––and afterlife. “If you arrive in the countryside early in the morning, you must visit your ancestors,” he says. “Ziyanda is now my ancestor.”

All images courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.