Introducing: Steven Molina Contreras

Lenin Mejorada was supposed to be away for two weeks. An immigrant from Peru, he was living on Long Island with his family for six years when he made a decision to obtain permanent residency in the US. On December 14, 2017, with short notice, Lenin, a maintenance worker at a Catholic church, left for Peru. His lawyers said the process wouldn’t take longer than two weeks. But after three weeks passed, Lenin missed his return flight home. “We didn’t have an answer,” his wife, Alma Contreras-Mejorada, said. “We didn’t have anything. And then, I was like, what’s going on?”

With her husband away, things were getting tight around the house. Alma asked her son, Steven Molina Contreras, to come home on the weekends to help out with babysitting. Steven, a photographer and student at the Fashion Institute of Technology, started commuting from Manhattan on weekends, mostly to look after his younger half sister, Abigail—Lenin and Alma’s US-born daughter, who was one and a half years old at the time—while Alma was working at a hair salon.

“My mom started to fill the gap when my stepfather was gone,” Steven told me in July, in a conversation with his mother, two days before Immigration and Customs Enforcement announced a series of “raids” in the US. “Obviously, a young child doesn’t understand why they’re not seeing their family member every day,” Steven said of Abigail. “And her father was gone for those three months.”

“It was more than three months,” Alma corrected.

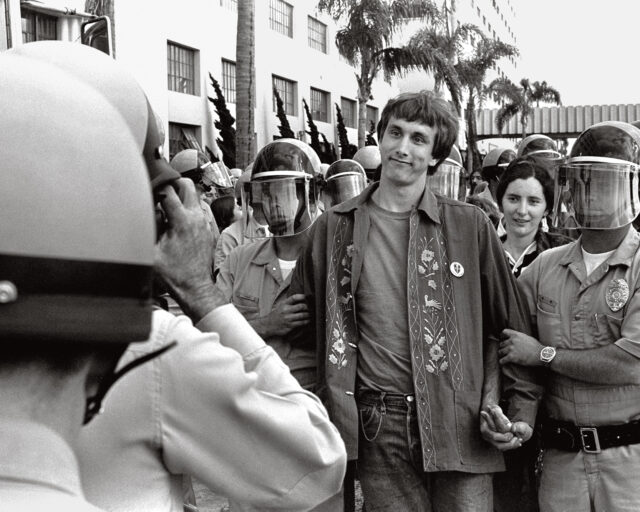

Steven was born in El Salvador in 1999 and moved to the US when he was six. “By all accounts,” he said, “I was as American as the Pledge of Allegiance I recited every morning in school.” As a child, he distanced himself from his Salvadoran heritage and raced toward assimilation, toward a sense of American identity. When people asked where he was from, he would confidently respond, “I’m from New York.” But his stepfather’s absence prompted a sudden shift in Steven’s relationship to his family. He had to step into the role of father figure; he had to figure out how to be a caretaker. Thinking of Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table Series (1990) and LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family (2014), he began to photograph his mother and half sisters, making evocative black-and-white portraits that consider the dynamics of a household living in uncertainty.

“Molina Contreras’s photographs have the power of evoking total recall of private Latinx family moments,” said Yxta Maya Murray, a writer and professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. “His ability to capture that intimacy recalls Roy DeCarava’s best portrait work, as well as Paola Paredes’s and Laura Aguilar’s.” In his series Mi Familia Immigrante (2018), Steven envisions his family as both documentary subjects and collaborators. He photographed his mother at moments when she was exhausted, and he gently guided certain scenes with a “performative” eye on composition, as in one of his mother and Abigail at a table, with Steven himself reflected in a mirror, all three trading gazes of introspection and concern.

“The camera starts as an object, a way of making, but becomes another present member of the family, partaking in the in-betweens of her family experience,” Steven observed of Paredes, an Ecuadorian photographer who also works between documentary and staged images. The same could be said of Steven’s own process, and the way his camera is an expressive instrument and a silent observer.

More than three months after leaving for Peru, Lenin returned home. “It was like everyone could finally breathe,” Steven said. “He was a resident. He was here. There was nothing that anyone could’ve done to take him away.” To mark the occasion, Steven made a formal family portrait, even though he’s not in the frame himself; he still thinks of his role as “the photographer.” Signaling a transition, he switched to color, as if the lights had suddenly come on, or a new spectrum of experience had been revealed. He soon decided he wanted to go to El Salvador, to reconnect with his biological father and make photographs of his extended family. “I realized the only way to unobscure my childhood identity was to return to El Salvador alone, with my camera in hand,” he said.

Steven’s Salvadoran family became willing participants in his project. They were glad, he said, that Steven had taken an interest in their lives, and that he was making images that went beyond the typical media representations of violence in El Salvador, a country that faced a devastating civil war in the 1980s, and has in recent years been beset by gang violence—one of the reasons why thousands have attempted to seek safety in the US. In April, over the course of a week, Steven made portraits of his father and his stepmother, his aunt and grandmother, which he collected into a series called Home Again, El Salvador (2019). He visited his father at the car wash where he works and lives, and they went swimming together. He told me he hopes his mother and sisters will return to El Salvador together “as a family unit, in the place where our origins began. I’m continuing to fill out our family tree.”

In Spanish, the word volver means to return, to go back, to start again. Lenin had to go back to Peru in order to return to the US. Steven had to return to El Salvador so that he could go back to his origins, to the beginning of his story. Even though he and Alma were reunited with Lenin, Steven said, “We still face those consequences of being immigrants in this country, having to go through the citizenship process, and having to struggle with the chance that the family we have now is not the family we can always have.”

Yxta Maya Murray noted that Steven’s “eye for detail robs you of your breath.” But in that moment of breath-taking, Steven also gives something back: a window onto the present tension around immigration in the US, and a stirring vision of an American family.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.