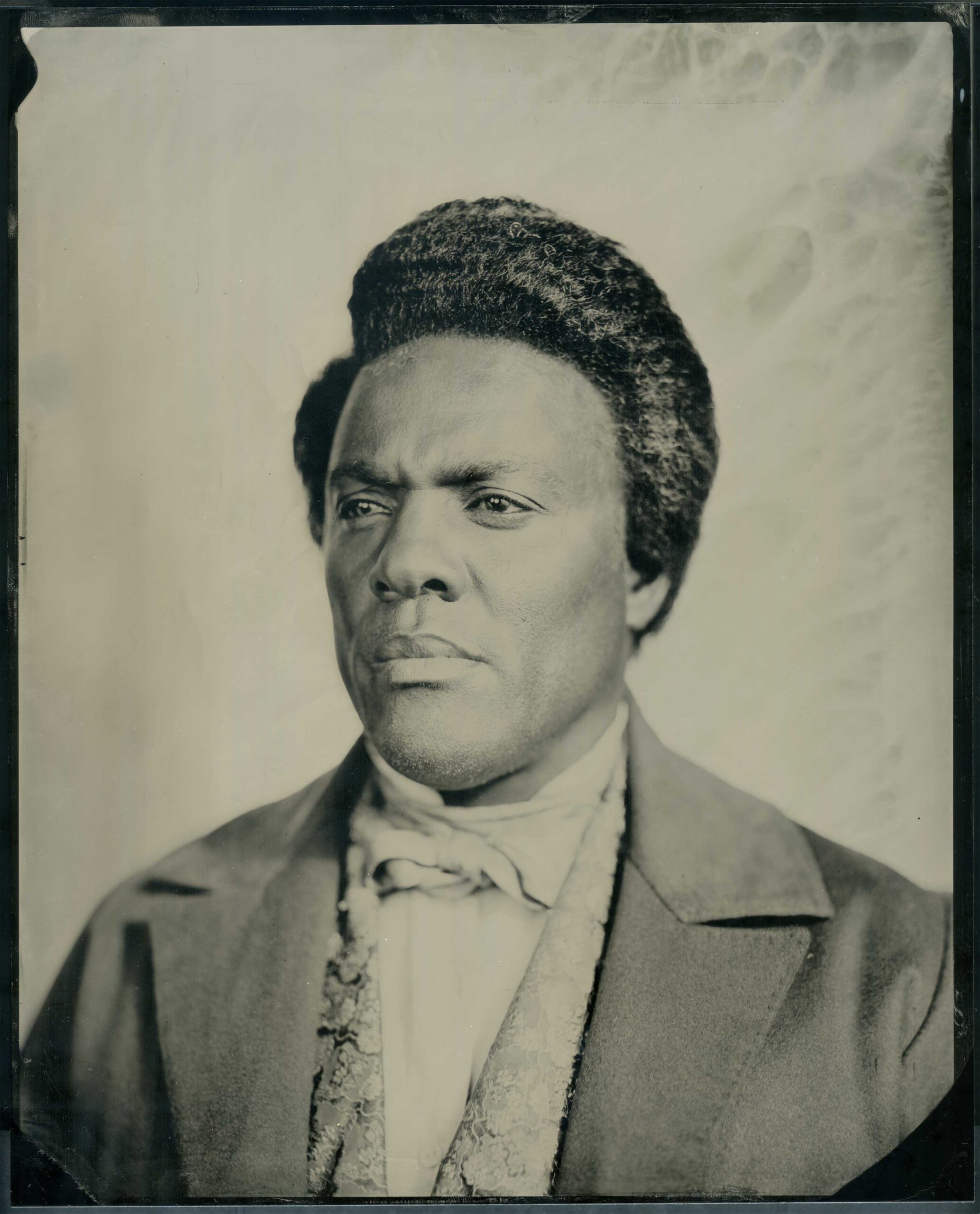

Isaac Julien, Lessons of the Hour Project Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (After Fredrick Douglass II), 2019

Isaac Julien’s latest multiscreen film installation Lessons of the Hour–Frederick Douglass reflects on the life and work of the nineteenth-century abolitionist, as well as Anna Murray Douglass, Helen Pitts Douglass, and several other powerful, single-minded women involved in campaigning against slavery. Commissioned and acquired by the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester, New York, where it was presented this spring concurrently with an exhibition at Metro Pictures in New York, Lessons of the Hour asks audiences to engage in call-and-response with Douglass, and the wealth of images and self-constructed narratives he left behind. It is both an homage to the enormity of Douglass’s sacrifice in the service of his “race” and a reflection of the limits of attempting to transform the violence inherent in racism using rational approaches.

Today, it is widely accepted that Frederick Douglass was the most photographed person of the nineteenth century—even more so than Abraham Lincoln, whose portrait had pride of place over the Douglass-Murray household’s fireplace, along with photographs of fellow abolitionists and supporters of women’s rights. In 2016, a new Douglass photograph was rediscovered during routine repairs for a scrapbook, which had been stored in the Special Collections of Rochester Public Library’s Local History and Genealogy Division. The scrapbook was created by William H. James, a postal carrier who lived in Rochester, New York, where Douglass and his first wife, Anna, lived from 1847 to 1872. Like all Douglass photographs, this latest find also portrayed a man fashionably dressed, poised, a gentleman of his era.

Between 1841 and 1895, Frederick Douglass sat for about 160 photographs. He viewed photography as a “democratic art” and praised its ability to bring the power of image-making and self-representation to a greater public. Douglass recognized that new photographic technologies made it possible for a larger public to enjoy images in their own homes, and allowed us to project, to the world, the self as we wished to be seen. He also understood that just as modes of travel and transport gave the Western subject freedom to be mobile—and thus further solidified their subjectivity—so too had the mobility of images: “The facilities for travel has sent the world abroad, and the ease and cheapness with which we get our pictures has brought us all within range of the Daguerreian apparatus.”

But as Thulani Davis reminds us, in the foreword to For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights by Maurice Berger (2010), “In every decade since escaped slaves began to produce narratives of their lives in bondage, there have been one or two African-Americans whose lives and images have appeared in the mainstream and have been characterized as representing our experience.” These couriers had to bear the burden of taking with them, wherever their image and narrative journeyed, a message intended to show white America (and fellow Black people) that to be Black was in opposition to prevailing white supremacist views, while—as Davis argues—anticipating how white audiences would likely receive one’s image and one’s person.

Julien’s video work does not allow audiences to walk away with an untainted perspective about photography, as would a man who came into his full subjectivity at the moment when the technology was made more accessible to the public. Rather, it is a painful reflection of the ways that photographic technologies, in which Douglass so fervently believed as a tool for transforming racist views, continue to be used—by individuals, institutions, and structures under which we all live—for subjugating Black communities. Instead of aiding our efforts at directing and amalgamating our subjectivity, photography continues, in the twenty-first century—just as it did within the early years of invention—to be used for surveillance, documentation, and further denigration of those regarded as racialized others.

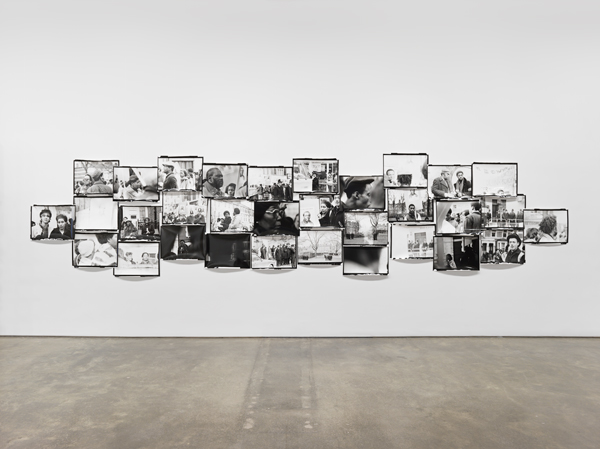

The photographic images in the entryway of Metro Pictures gallery were both intimate and expansive, consisting of small tintype portraits that harken our collective historical memory of nineteenth-century photographs, and large, lush color stills from the video works. To these, Julien added black-and-white photographs documenting protests that followed the killing of Colin Roach, a twenty-three-year-old black man who was shot to death at the entrance of an East London police station in 1983. (Julien’s 1983 film, Who Killed Colin Roach? engages more fully with this brutal incident.)

But the main attraction is Julien’s new video installation, filmed at the Royal Academy of Art in London, which splices reenacted montages of Douglass’s glorious, powerful presence, and samples three of his most powerful lectures: “Lessons of the Hour,” where Douglass addresses lynching in the South; “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July,” where he questions the meaning of freedom to those in bondage; and “Lecture on Pictures,” where he marvels at the power of photography to empower its subjects, giving them autonomy over how wished to represent themselves. He believed that these “truthful” depictions would win over stereotypical depictions that aided white supremacy.

When Douglass reflects on freedom, or lynching, we also see footage of cotton fields that fill the screens, or a great, hulking tree, which creaks with its burden. Toward the end, as Douglass questions the legitimacy of the Fourth of July as a universal celebration for all Americans, we see some of the screens fill with grainy, contemporary video. This is aerial surveillance footage, made by the FBI, of the Baltimore riots of 2015 following the acquittal of all police officers involved in the death of twenty-five-year-old Freddie Gray, who suffered a severe spinal cord injury while in the back of a police van in Baltimore on April 12, 2015, and died a week later as a result.

In order to provide a more complex view of Douglass, Julien worked on developing what he calls his tableaux vivants in which he details Douglass’s relationships with the women in his life. These intimate, intertwined portraits indicate that this great man’s accomplishments were accompanied primarily by the kindness, financial support, intellectual companionship, and emotional care of women. Douglass’s first wife, Anna Murray, a born-free black woman, was married to Douglass for forty-four years, bore their five children, and maintained their home and family while Douglass traveled throughout the United States, and during a two-year journey in Great Britain. Following Anna’s death in 1882, two years later, Douglass married Helen Pitts—educated, white, raised in an abolitionist family, twenty years his junior.

Anna Murray appears in several of Julien’s photographs, sometimes accompanying her husband on a train or together with a group in a parlor. In one sumptuous image, she is seated on her own; she appears as a woman as determined and forward-thinking as any of her counterparts—though she did not have the advantages of being able to read and write in a world that made literacy a requirement for proving one’s humanity. That Murray and Pitts were not only facilitators in Douglass’s journey, but collaborators in the political work of self-fashioning, is evident in scenes where Anna Murray is shown at her hand-cranked sewing machine, attending to a royal blue velvet garment, which allows Douglass to carry himself regally as he gives public lectures. We know that Douglass’s life and work were financially dependent on others and their charity. When Julien’s video work shows Helen Pitts at her desk, reading correspondence and writing, we know a small part of what it must have taken to generate that support.

All images © the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

Douglass maintained his complicated perspective—which, in the twentieth century, W. E. B. Du Bois named “double consciousness”—throughout his life. Douglass seemed fully aware of where he came from, and what his extraordinary education, along with others’ financial and emotional support, allowed him to accomplish. He often contrasted his life as a barefoot child of slavery, dressed in rags, to the well-dressed visitor of the White House, an exemplar of respectability. Julien’s film adds necessary complexities to versions of history that often portray great men like Douglass as exceptions. Julien also complicates Douglass’s laudatory commentary on photography, showing how this remarkable tool—so often subverted by powerful systems of authority—can still move us to reclaim freedom and dignity.

Isaac Julien: Lessons of the Hour–Frederick Douglass is on view at Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, through May 12, 2019.