James Welling: Monograph

Monograph / Image 1

Monograph, a career-spanning survey of photographs by James Welling, opened at the Cincinnati Art Museum last Saturday. The exhibition, organized by curator James Crump, synthesizes Welling’s disparate photographic series, which range from abstract photograms to documentary-style portrayals of the New England landscape.

Aperture has published James Welling: Monograph to accompany the exhibition, which will also travel to the Fotomuseum Winterthur in Switzerland. This book is now available for purchase in our online store. Below are two short excerpts from Museum of Modern Art curator Eva Respini’s conversation with Welling, one of four extensive texts included in the book. The conversation took place on March 27, 2012, in New York.

Monograph / Image 2

Eva Respini: You refer to yourself as a photographer rather than as an artist. Why is it important for you to self-identify as a photographer?

James Welling: No one in my generation called themselves photographers, even if they were doing photography exclusively. But, for me, it was an acknowledgment that I wanted to think of my work in the context of the history of photography as well as the art world.

ER: You’ve acknowledged Paul Strand as a key influence. The modernist tradition of photography is antithetical to the use of photography in conceptual art and in the work of your teachers at CalArts [California Institute of the Arts], such as John Baldessari. You are self-taught in photography, yet now you’re one of the most influential artists and teachers of photography. How did you make that leap?

JW: I got to Strand because I was totally enamored of Hollis Frampton’s writings and films. In the early 1970s, Frampton wrote on the work of Edward Weston and Strand in Artforum. So, here was a structural filmmaker thinking seriously about Strand. When I moved to LA in 1972, I saw the Strand retrospective at LACMA and that blew my mind. A year later, I stumbled upon his Mexican Portfolio in the CalArts library. His pairings of religious sculpture with portraits seemed strikingly contemporary.

When I was a graduate student at CalArts I wasn’t making my own photographs. I was interested in media images, mostly portraits, and for my 1974 thesis show I made photo collages from books and magazines. After I graduated, I spent about a year and a half trying to figure out what to do. It was a hard time. I read a lot, and I made small watercolors and photo collages. In December 1975, Matt Mullican and I were hiking in Connecticut. Frustrated by my confusion about what to do, he joked, “You’re always talking about photography—you should just get a camera like Ansel Adams and take photographs.” I had borrowed my sister’s Minolta at the time, and Mullican’s admonition got me thinking seriously about photography. It never occurred to me until then that I could think of myself as a photographer.

ER: You’re self-taught in the history of photography, too. You absorbed images mostly through reproduction, which is, of course, a big part of how the medium is disseminated. You have no signature style and work in a variety of genres with different cameras and processes. Do you think your self-taught beginnings have allowed you to be open and experimental with the medium?

JW: Being self-taught in photography has allowed me a certain freedom. There’s a way in which I explore some aspect of the history of photography with each project, although this is unconscious and not at all systematic. Early on, I worked with Polaroids. I made a camera out of a shoe box and then moved to a four-by-five view camera. More recently, I’ve worked with photograms and trichromatic color.

Hollis Frampton wrote about the “knight’s tour,” a chess fantasy where the knight can occupy every position on the chessboard. For Frampton, his knight’s tour would be a tour of all possible films from the beginning of the medium till now. The idea of a creative tour around photography is very compelling to me.

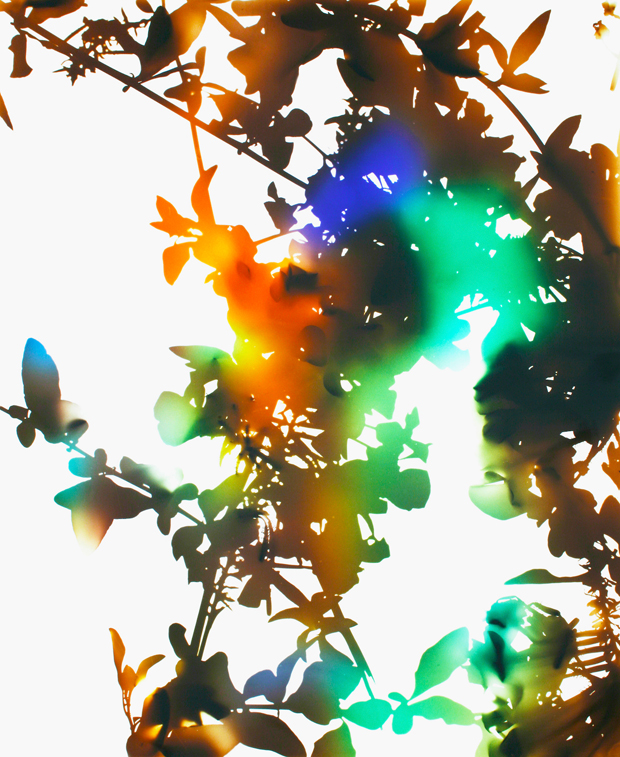

21, 2006, from Flowers. Copyright © James Welling. Courtesy Cincinnati Art Museum, David Zwirner Gallery, New York and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

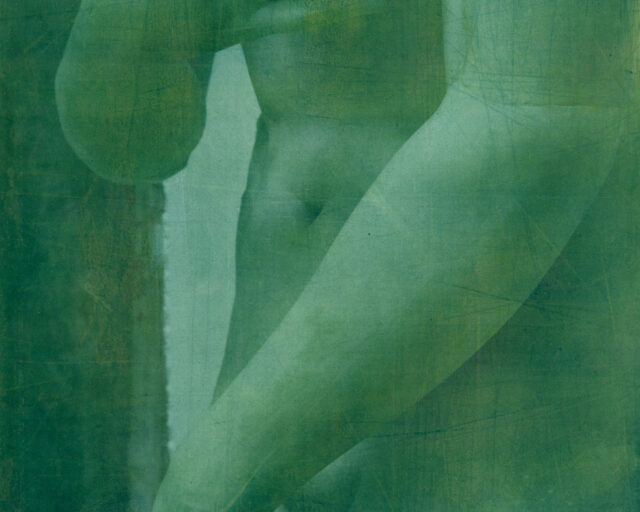

9-7, 2005–06, from Torsos. Copyright © James Welling. Courtesy Cincinnati Art Museum, David Zwirner Gallery, New York and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

[ … ]

ER: When you were making the Glass House pictures, you held filters and gels in front of the camera. I imagine you’re juggling camera, gels, prisms—it’s almost a performance.

JW: I think every photograph has performance built into it on a couple of levels. There’s the performance of the photographer making a picture. Converging on a spot, various preparations, getting lucky—all of this involves performance. Then you have the performance of printing the photograph. My Glass House photographs accentuate the performance of their making by intervening with things that I put in front of the camera. I started out with a few colored filters and then gradually added more filters, then curved Mylar, clear and colored glass, and finally a scientific diffraction grating.

ER: In a lot of your pictures, there’s a scrim, a screen, or a texture that’s in front of the lens.

JW: I’ve always found the idea of the scrim or the screen compelling as a stand-in for the photographic process. In Light Sources, one of the first images I made, Meriden, shows the sun peeking through tree branches. I thought of it as looking up at the light source of the photographic enlarger from the point of view of the negative. In the Andrew Wyeth photographs, there’s an image I made, in Maine, of the moon in a cloudy sky between pine trees. The idea is similar to Meriden: we’re looking at a light source, which is partially obscured.

ER: Is chance attractive to you? When you were at Carnegie Mellon, Merce Cunningham and John Cage were in residence.

JW: They were on campus for a week. Seeing Cunningham rehearse and dance for a week and talking to Cage, both were life-changing for me. I read a lot of Cage, and I studied modern dance for a year at the University of Pittsburgh.

ER: Of course, in photograms there’s chance. But yet there is a side of your practice that seems rigorous and meticulous, with little opportunity for chance.

JW: With New Abstractions, I became interested in thematizing the darkness of photography, the part of the medium where you can’t see what you’re doing. With that work, I started by randomly dropping strips of Bristol board onto photographic film in total darkness. It’s as though a dark curtain is pulled around the act of making the work. Photography has to be created in darkness, both literally and figuratively. It’s a very special and unpredictable medium. I think this gives way to a desire for control or mastery in the way some photographers try to plan everything in the picture.

Last week in my senior studio class, we were talking about things that are unplanned. The problem is this: you don’t want to be working completely in the dark, but if you have too much control, then nothing works out well. There’s a great quote by the filmmaker Jean Renoir: “You control everything, you plan everything, but you always leave a door open for chance to enter.” I try to let in the unexpected as I’m working like mad to control it.

—

Eva Respini is associate curator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. She has organized numerous exhibitions on contemporary art and photography at MoMA, including the recent, critically acclaimed Cindy Sherman retrospective, Boris Mikhailov: Case History (2011), Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography (2010), and Into the Sunset: Photography’s Image of the American West (2009).