How to Capture an Intimate History

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Blondine in front of the door, Rue des Lombards, Paris, 1976–77

Courtesy the artist

Jane Evelyn Atwood is not the kind of documentary photographer who leaves once she has the right pictures. Instead, Atwood spends years getting to know her subjects and their communities. Atwood’s bodies of work are photographic essays, perhaps in their purest form—where the power of each image lies in the seemingly impossible balance between an intimate instant and a glimpse of history.

An American born in 1947, Atwood moved to Paris in 1971, and has been based there ever since. In 1975, after encountering a woman named Blondine, Atwood began photographing sex workers on rue des Lombards and in the Pigalle neighborhood by night, while working at the local post office by day. Atwood received the first W. Eugene Smith award in 1980. Other major personal projects have included an eighteen-month reportage of a French Foreign Legion regiment (1983–85); a three-year project in Haiti (2005–8); and a ten-year investigation of women in prison across North America and Europe (1989–1999).

In early 2019 Atwood’s photographs of James Baldwin were part of the exhibition God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, curated by Hilton Als, at David Zwirner gallery in New York. A series depicting transgender sex workers, Pigalle People (1978–79), was shown at the 2018 edition of Les Rencontres d’Arles in France, and is currently on view at the Maison Doisneau, Gentilly. I recently sat down with Atwood to look back on forty years of not only image making but also activism, love, and loss.

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Prisoner in the prison workshop, Les Baumettes prison, Marseilles, France, 1991

Courtesy the artist

Claire Debost: Last spring, Too Much Time (2000), your book focusing on the condition of women in over forty prisons throughout Europe and America, was adapted into a play by Fatima Soualhia Manet, an actor and director. Could you talk about these translations or adaptations from the experience of these women in prison, first to photographs and then a play?

Jane Evelyn Atwood: It was a fantastic experience. I was fearful, but even when I was actually doing the work, there was something so surreal and unbelievable about what I was witnessing and experiencing that it felt theatrical. A playwright couldn’t have made up better stories, yet they were real, they were real people. When I was working on the project, I would have these women in front of me and they would tell me everything because—and I say this without pretension—they knew that I was a way that they could have their voices heard, and they had never had that before. That’s why I made a book that was so full of captions and text. I felt that if I had a “duty” (and I dislike that word), it was to not betray those women with all the information I had gathered from them, and to tell it to other people who know nothing about prison, to tell what it’s really like to be inside.

For the play, I thought a simple mise-en-scène would make this even more theatrical, would work on the stage, and it would prolong the life of the book. What was really intelligent about Fatima was that she realized that it wasn’t just the story of prison and the women who were in there; it was also the story of the photographer who goes into these prisons and has this experience. So, she incorporated that into the prison stories, and that’s what makes this play different from everything else out there. Our play stands apart because it combines video, photography, and theater. And nothing is made up, so it’s that much more shocking, that it’s not fiction—and it’s still completely up to date, because conditions have only gotten worse. It’s timeless, for the moment.

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Street scene, Gonaïves, Haiti, 2005

Courtesy the artist

Debost: A lot of your work touches on social issues, such as domestic abuse or prostitution, yet the images are sensitive and personal. How do you begin to work on a project and how does it evolve?

Atwood: I see something. All of my projects start with a visual cue. That can be in real life, in a newspaper, in a magazine, or even on TV sometimes. Every once in a while, I have an assignment that turns into a personal project. For example, Haiti was originally an assignment but it wasn’t enough for me, so it became a personal project. Then I get “bitten” by the subject and very quickly I know whether I want to begin the personal project or not. As soon as I know that I want to do it, I do everything I can to organize my life around the project: finding the money, finding where and when I can do it. With most of my subjects, I want to photograph because I have a lot of questions myself. My photography is about interrogations: it’s always questioning and wanting my questions to be answered.

This is contrary to what a lot of people say about me. They say I’m an activist and I’m a feminist—of course I am a feminist, as all intelligent women must be today. But, really, the very first activist story I did was quite late in 1987, with the photo-essay on a French man named Jean-Louis, who was dying of AIDS. He was the first person in all of Europe to allow himself to be photographed and published in the press saying he had AIDS. Before that, there was nothing contentious about prostitutes when I was making the work Rue des Lombards in 1975, even though later some feminists made it their cause. But it was a testimony—it was like, wow! I saw these incredible women and this is what I experienced with them and I’m giving it to all of you. I wasn’t trying to change anything or take a position on it.

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Jean-Louis, the first person with AIDS in Europe who allowed himself to be photographed to appear in the press saying, “I have AIDS.” Paris, 1987

Courtesy the artist

Debost: Even as you discuss your process, it is clear that you spend years on every project you work on. Too Much Time, for example, took almost ten years to complete. Have you developed deep relationships with some of the people you have photographed along the way?

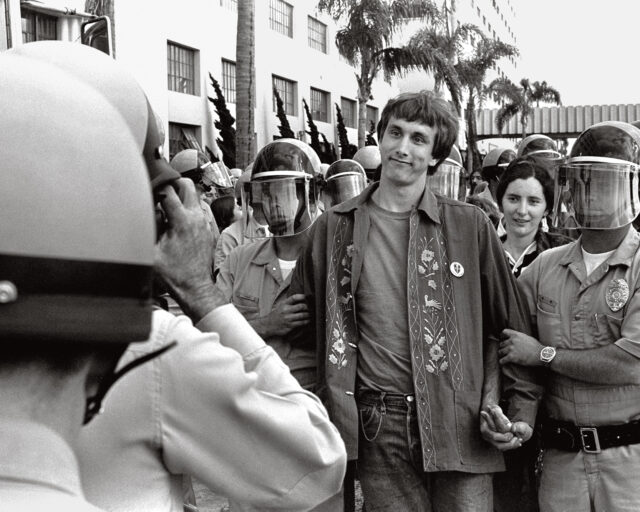

Atwood: Well, it’s true that, with many of the projects, I’ve had some sort of “bonding experience” (as you say in the States) with certain people. Blondine, who I met while working on Rue des Lombards in the ’70s, was the most important; not only because she was such a remarkable person but also because the prostitutes on the rue des Lombards were the first people I photographed. I didn’t know what I was doing, and Blondine was very patient with me; she would wait while I was trying to focus my camera. But I think also that was maybe the reason that she let me in; I wasn’t a threat to her. I didn’t have a carte de presse or a ton of equipment, and I could hardly speak French. She was curious about me just as I was curious about her.

I continued that very privileged friendship with Blondine until she died in 2013. It was Leonard Freed who told me once, “You’re choosing a kind of photography that is very lonely; you can’t take these people home with you.” I never forgot that. He meant that it’s a special kind of friendship. I was privileged that Blondine let me into her world, and I let her into a part of my world, the photography part. But she’s the one who said, “Don’t invite me to your house.” She protected me from herself at the beginning. She said, “You’re a cavette,” meaning a “straight” person, someone not in the milieu of prostitution, “and I’m a street prostitute.” She was setting the boundaries, and she was right because it wasn’t always la vie en rose. Sometimes she threatened me; she was an irrational person who had no rules.

Then there was Jean-Louis, the man I photographed for my AIDS project in the late ’80s, who was very special. Our friendship only lasted four months and ended because he died. I said to him once, “You know, I’ve only seen you once not wearing pajamas.” We went out one night because he wanted to show me a gay restaurant. The effort to do that almost killed him. That was the only time I ever saw him in real clothing. We were in this creative bubble, making photos, but when somebody is dying there is no bullshit. If you get along, immediately everything is out there. He talked about things that were very intimate that he probably would never have talked about with other people without knowing them for a long time, but he didn’t have a long time.

I do feel it’s important to have some kind of boundary as a photographer or you can get in trouble, especially as a woman. I know other photographers who have no boundaries at all, that’s their way of doing it. I try to always impose myself as The Photographer and not as something else.

Jane Evelyn Atwood, James Baldwin with a bust of his likeness by Lawrence Wolhandler in his hotel room, rue des Grands Augustins, Paris, 1975

Courtesy the artist

Debost: Some of your photographs were recently included in the exhibition God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, curated by Hilton Als. What was your relationship with James Baldwin? Can you tell me more about these intriguing photos of Baldwin with a sculpted bust of himself?

Atwood: I was so lucky. It’s thanks to Larry Wolhandler, who is one of my closest friends and who was in Paris studying sculpture at the Beaux-Arts. It was at the very end of 1975. I had just bought my camera, and suddenly he called me one day and said, “You’ll never believe who I’m sculpting.” “Who?” I said, and he answered, “James Baldwin, and he said that you can come with your camera and photograph him!” In high school, and at Bard, I had studied James Baldwin, and he was a huge star. He was like a hero to me. He used to stay in a very fancy hotel on rue des Grands-Augustins. Larry and I went there often; he was always with a group of guys who worshipped him. We would go to this one restaurant in Saint-Germain-des-Prés: we would all drink whiskey and smoke, and listen to Jimmy. We had many nights like this. You could listen to him all day and all night. He was an extraordinary person.

He died on December 1, 1987. Jean-Louis had also just died. A friend of mine who was also a photographer called me and said, “Have you heard about Jimmy?” I was still devastated by Jean-Louis’s death, and was very fragile, and then there was the news about Jimmy. I felt like the world was coming to an end.

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Blondine in the hallway. Rue des Lombards, Paris, 1976–77

Courtesy the artist

Debost: You talk about the boundaries between you and the people you photograph. What about the responsibility that you owe to them and to yourself when putting the photographs out in the world? Are there times when you have questioned whether to publish a photograph or not, and how do you work with that?

Atwood: The truth is, when you ask permission to take photographs, it can’t be conditional; you can’t let other people make decisions about which photograph you can and can’t use. It’s difficult but that’s the truth. You have to earn enough trust from the people you photograph so that they trust you to choose the right photographs. That means you have to follow the photographs for the rest of your life; you have to become a control freak and follow how and when those photos are being used, with what captions, et cetera—and that’s a whole lot of work that many people aren’t ready to do. And now with the internet, it’s practically impossible because you can’t really control images, but you can do your best.

You can never satisfy everyone. Even people who may have loved you when you photographed them might be angry at you about which photograph you use. There was a prostitute in my very first book, Daily Nightlife (Nächtlicher Alltag, 1980), who’d signed the release, who I had spent a lot of time photographing. But when the book came out she was furious. She yelled, “You bitch! You put me in a pornographic book!” It was no secret that she was a prostitute; everyone knew it, and my book was a book about prostitutes. But I didn’t put her photograph in the second book because I didn’t want to have any problems, and I certainly didn’t want to make her life unhappy. Who knows, really, why she said that; maybe it made her see what she’s doing, and she was confronted with the reality of her life.

When I make a book, I try to be very fair about how many of a certain kind of photograph I’m going to use. I’m not going to overdo the horrible, grotesque pictures. For Jean-Louis, I had a lot of photos that I didn’t use because he was so thin, he was like a skeleton. I included a couple of photographs like the one of his back, which shows how sick he was, and that’s enough—but you have to show it, too. You can’t be sentimental about AIDS or cancer, you have to show what it is. But one or two photos is enough. It’s dosing, and dosing is very important.