Against Occupation

Japanese curator Rei Masuda discusses how postwar Japanese photographers adapted to a new era.

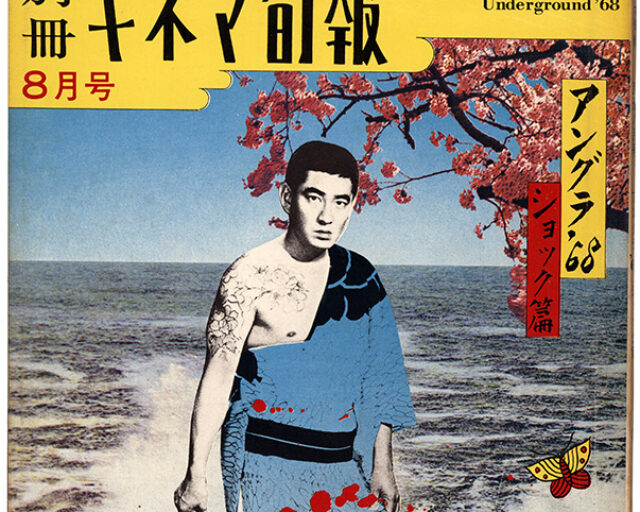

Hitomi Watanabe, from the series Shinjuku Contemporary, 1967-68

© the artist

In 1960, the U.S. and Japan re-signed a security treaty known as Anpo, which maintained U.S. dominance in East Asia, and allowed American troops to be stationed in Japan—indefinitely. In a few short years, the U.S. had flipped from being an enemy to an ally. At the same time, American culture was becoming increasingly pervasive in the country. Protests were staged across Japan in response to these societal shifts—and photographers were soon engaged.

Rei Masuda, head curator of photography at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, has long studied the rich photography of this period, producing traveling exhibitions such as Gazing at the Contemporary World: Japanese Photography from the 1970s to the Present that have introduced an international community to key ideas and figures. Here, Tsuyoshi Ito of A/fixed speaks with Masuda about his work about post-war photography from Japan.

Tsuyoshi Ito: What first drew you to photography, and which photographers had an influence on you?

Rei Masuda: In 1989, while I was attending university, there was an exhibit on the 150-year anniversary of the invention of photography. More than the photographs themselves, it was that visceral expression of culture and history that inspired me. When I was young, I greatly admired Walker Evans and Robert Frank.

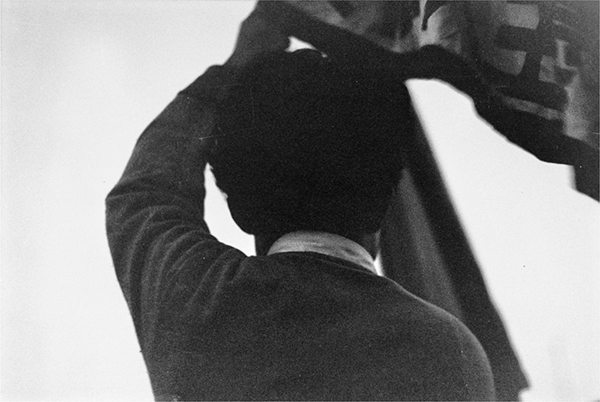

Kazuo Kitai, Flag, Yokosuka, Kanagawa, 1964, from the series Teiko (Resistance), 1964-65

© the artist

Ito: When people think about the radicalism of 1960s and ’70s Japan, student protests are usually the first thing that come to mind. Many segments of society were taking part in the political movements. What’s your take on this highly fluid period during which not only students, but also ordinary citizens from all walks of life, were spurred to action? What kind of influence did that dynamic have on photographers?

Masuda: During the ’60s and ’70s there were many influences on photographers, not the least of which was the protest against the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, known as Anpo. That time of unrest gave birth to many exceptional documentaries criticizing the heavy-handed powers that prevailed. In the decade that followed (i.e., the 70s), Japanese society became ever more complex, as did the causes of unrest. Protests expanded to include anti-Vietnam War activism, campaigns to return Okinawa to Japanese control, and anti-Narita Airport movements, among others. Just as in the ’60s, photographers were there to document it. The photography magazine Provoke is often seen as a symbol of these times, but it hardly stood alone. Photographers were documenting events, people, and movements in various, unique ways. It was really a special era.

Kazuo Kitai, Sanrizuka Protesters, 1969, from the series Sanrizuka, 1969-72

© the artist

Ito: During the ’60s, when Anpo was ratified, the aims of both photographers and ordinary citizens had a common cause. At that time, what attracted you to Provoke?

Masuda: Provoke rejected the established photographic aesthetics. Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira were embracing a radical new form of photographic expression. This style was a reflection of the times, of the counterculture and political movements that were peaking in the late ’60s.

Ito: The campaign against the Anpo Treaty was one of the more visible aspects of Japanese–American relations, and the most polarizing social issue of the time. Many Japanese people appreciated American artists and desired American material affluence, but simultaneously resented the pervasive American presence in Japan. What kind of influence did this have on Japanese photography?

Masuda: Japan’s relationship with America was inextricably linked to both photographers and photographic works produced at the time. This is especially evident when looking at the work of photographers like Shomei Tomatsu, for whom the American occupation of Okinawa was a major theme, and Miyako Ishiuchi, who grew up in Yokosuka, in the shadow of an American military base. They were a generation apart and not geographically close, yet Japanese–American relations had an impact on both of them, and not just on their characters. I can’t say that all Japanese photographers were affected in the same way, but the changes in post-war Japanese society are certainly reflected in the people and photography of the time.

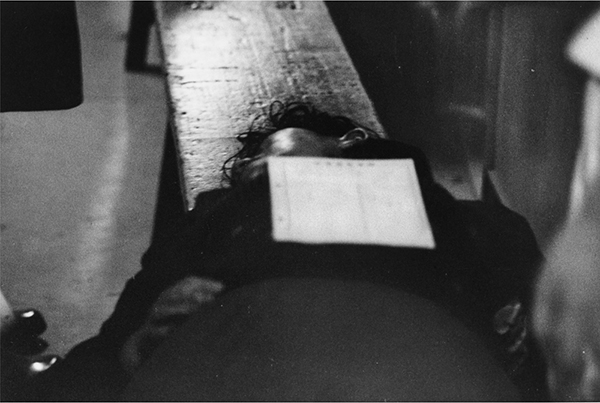

Kazuo Kitai, Injured Protestor, Yokosuka, Kanagawa, 1964, from the series Teiko (Resistance), 1964-65

© the artist

Ito: Are there any other photographers that come to mind when you think of American influence on Japan?

Masuda: Take Daido Moriyama, for example. You can clearly see the influence of American contemporaries like Andy Warhol in his photography. At first glance some of his work seems critical of America as well. Though I think that it is more a criticism of America’s influence on and occupation of Japan, rather than America itself. If you consider his formative years, it’s easy to see how he could have such mixed feelings. As a teenager during World War II, he knew that should the war continue, his fate would be to give his life for his country in the fight against America. In post-war Japan, during the occupation, his view necessarily changed as he lived in close contact with the former enemy. Photographers of the day had very complex and unique relationships with America.

A/fixed’s inaugural publication, Provoke Generation: Japanese Photography, ’60s-’70s will be released in April 2017.