A Photographer Traces the Ghosts of Loss and Trauma in Southern Africa

Jo Ractliffe’s expansive new photobook demonstrates how words and pictures bring historical memory into sharp relief.

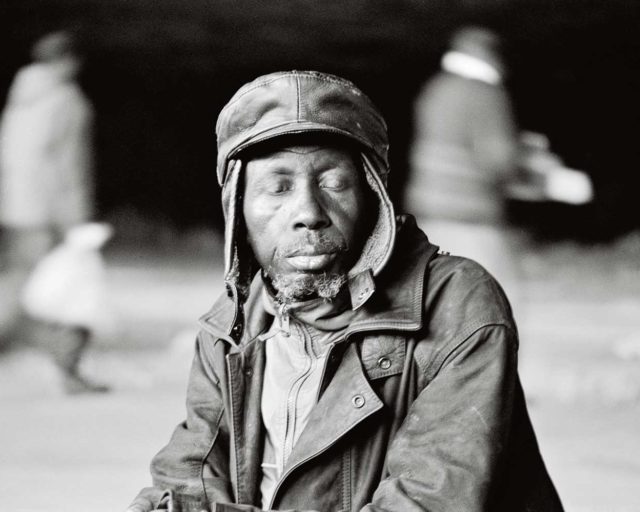

Jo Ractliffe, On the road to Cuito Cuanavale IV, 2010, from the series As Terras do Fim do Mundo, 2009–10

Nearly four hundred pages into Jo Ractliffe, Photographs: 1980s – now (Steidl and the Walther Collection, 2020), the first comprehensive survey of the South African photographer’s thirty-five years of artmaking, is a graceful short story by Emmanuel Iduma. “Rendezvous: A Fiction” follows the journey of an unnamed man in an unnamed town who is searching for signs of the father he lost to war decades prior. It is strewn with footnotes, by which Iduma intersperses this story with close reads of key photographs by Ractliffe. These asides provide the momentum for an understated narrative of family mourning and the long shadow of war. “She stands facing seven dangling overalls, held by long strips of twine and tethered to narrow branches,” Iduma writes of Ractliffe’s photograph Roadside stall on the way to Viana (2007). “Presences without bodies, exoskeletal men. They are hung there as if in readiness. Later, when the ghosts come, they will need to be clothed.”

They will need to be clothed. So much of Ractliffe’s photographic practice has hinged on clothing ghosts. She attends to the ghostly imprints that political violence has left on the landscapes of South Africa in the wake of apartheid, and on those of Angola in the wake of civil war. Photographs: 1980s – now narrates this career-long commitment, culling work from each of the artist’s major series, such as Crossroads (1986), depicting the titular township where bulldozers razed people’s homes to the ground during the State of Emergency, and Vlakplaas: 2 June 1999 (drive-by shooting), made during the artist’s visit to the farm that had once served as headquarters for the apartheid government’s covert hit squad. In these and many other photographic series, Ractliffe focuses her lens not on explicit scenes of human violence but rather on the signs of its haunting: the riven terrain where somebody’s shack once stood, a lone man in the background taking the measure of what is lost; or the ominously blurred gate that marks the way to Vlakplaas, a terror best glimpsed askew.

The book features both texts written by Ractliffe as well as epigraphs from a range of literary sources to introduce the different bodies of work. Some of these text-quote pairings are adapted from Ractliffe’s original exhibition statements or earlier monographic book publications, like her 2008 volume Terreno Ocupado (Warren Siebrits, 2008). These missives, which mediate the image sequence, offer direct insight into Ractliffe’s artistic framework at the time the works were made. However, it is the text contributions appearing at the book’s end, which open with Iduma’s invocation of the ghosts, that truly illuminate the unique rhythm in which the photographs can be read, while also distinguishing this volume as more than a recapitulation of the artist’s prior projects.

In addition to Iduma’s idiosyncratic story, these contributions include extracts from an interview between Ractliffe and Artur Walther, an original essay by curator Matthew S. Witkovsky, as well as a selection of essays and reviews previously published in various international journals, magazines, and online platforms, such as, notably, an incisive essay by Okwui Enwezor. Witkovsky’s piece discusses Ractliffe’s disinterest in presenting her images as a healing antidote to the profound violence that has marked the world around her. “Her work is not aimed at comprehending trauma per se,” he writes. “Rather, it replays trauma to make clearer the historical conditions that have normalized its occurrence.” Witkovsky posits that both this replaying of trauma as well as the incorporation of photographic montage are “structuring principles (rather than subjects) in Ractliffe’s work.”

The close-knit relationship between trauma and montage becomes clear when flipping through a series like Vlakplaas, in which a continuous strip of black-and-white film bleeds peripheral and disjointed views of the farm into unnatural unity—a “physically disturbed openness,” as Witkovsky puts it. The violent acts that haunt this site, Ractliffe’s sequence suggests, have caused a fundamental disruption to the landscape and our own sightlines.

Ractliffe focuses her lens not on explicit scenes of human violence but rather on the signs of its haunting: the riven terrain where somebody’s shack once stood, a lone man in the background taking the measure of what is lost.

A literary intervention like Iduma’s “Rendezvous” mirrors this disruption. The close read of Roadside stall on the way to Viana that opens the story immediately invites the reader into a visual and narrative meandering. The vignette is footnoted; our eyes travel down the page; move backwards and forwards in the book’s pages to find the image referenced; then linger on the annotated insights. Then the story moves on, intentionally staccato, to an entirely different scene that returns us to our main protagonist, that unnamed man tracking the ghost of his disappeared father. As “Rendezvous” continues, the footnotes begin to build a more elaborate subtext, making space for a greater span of literary references, critical analysis, and creative musings than could fit in the bounds of the main text. In one thrilling tangent, Iduma leaps from a close reading of the “R-shaped” figure of a man standing apart from a crowd in Raising the flag, Riemvasmaak (2013) to explore the resonances of the words this subject’s pose bring to mind: from the French word “limicole,” worm-like, to, soon, “limen,” a threshold. In this way, the text acts as a limen for understanding the full texture of Ractliffe’s work.

The first image Iduma describes, with its “exoskeletal men,”was made in Angola’s capital, Luanda, in 2007, as part of Ractliffe’s landmark series Terreno Ocupado, five short years after the end of the country’s multi-decade civil war. Yet Raising the flag emerges from Ractliffe’s later series The Borderlands (2013), which considers the aftermath of the Angolan war within South Africa’s borders. Iduma’s story blurs these chronological and geographical distinctions—its invitation to zigzag between the book’s pages and Ractliffe’s bodies of work parallels the destabilized time of traumatic memory, unifying disjointed scenes, enforcing its own kind of visual montage.

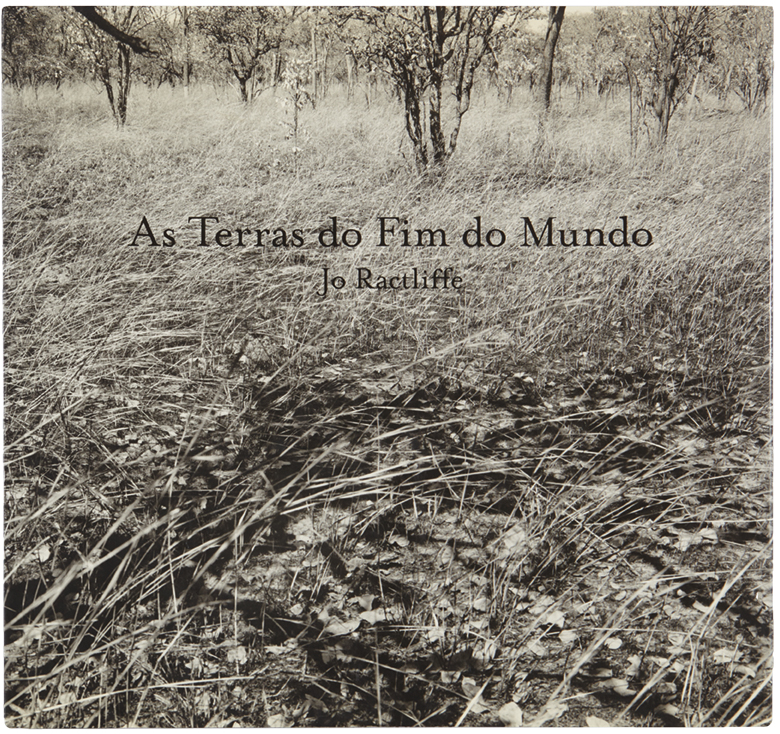

Creative text has long played a crucial role in reading Ractliffe’s images. Her out-of-print volume As Terras do Fim do Mundo (Michael Stevenson Gallery, 2010) traces the two years Ractliffe spent following ex-soldiers through the Angolan countryside to explore the landscape as a site of both trauma and mythmaking. Alongside her compositionally dense images of spaces where the ex-soldiers had once fought is an expansive personal narrative from Ractliffe about her time there. Like Iduma, she zigzags across the page in rife vignettes, attempting to track the landscape’s unclothed ghosts. “I have been trying to untangle the convolutions of this impossible war,” she writes towards the end. “I imagine the stories, all their versions and others, unheard, unspoken, time and events, all of it, moving in a slow steady converge like iron fillings towards a magnet.”

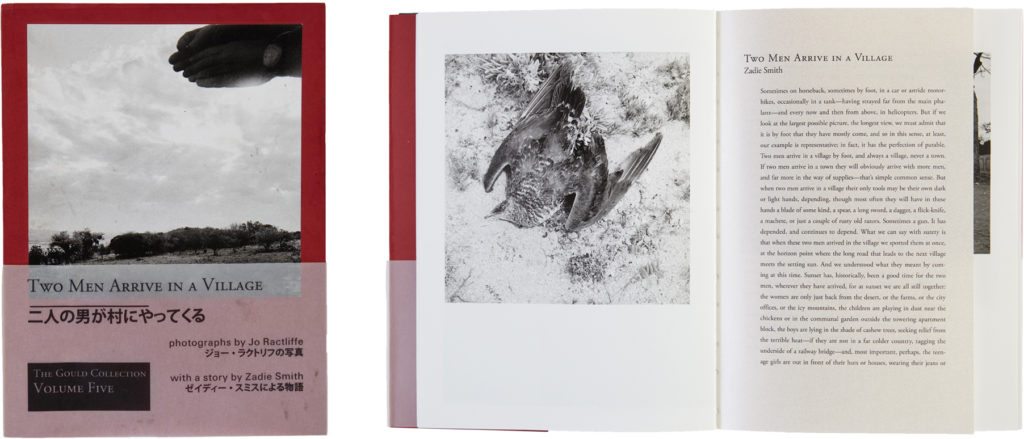

In a recently published volume from The Gould Collection, Two Men Arrive in a Village (2021), a literary narrative and a penchant for mythmaking play an equally central role. Ractliffe’s subtle, somber images made between 1985 and 2019 across southern Africa are paired with a short story by Zadie Smith that reads as a parable, and similarly probes the unfolding of political violence. Smith’s contribution, like Ractliffe’s work, and like Iduma’s own short story, destabilizes time and geography, and revels in ambiguities. Jostling with the idea of narrative certainty, Smith follows the arrival of two pointedly unnamed men to an unnamed village who are at once highly particular—“It goes without saying that one of the men is tall . . . a little dim and vicious, while the other man is shorter, weasel-faced, and sly”—and completely allegorical, standing in for the countless harbingers of political violence who pass through local communities and leave haunted lands in their wake.

Courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

A little less than halfway through Two Men Arrive in a Village, one of Ractliffe’s more explicitly brutal images appears. This image, untitled and undated like the rest of the book’s sequence, shows a skinned, skeletal animal, dangling on a strip of twine against a building of brick, concrete, and ribbed steel. Its nakedness is a gruesome, disjointed counterpart to Ractliffe’s exoskeletal men. In the aftermath of war, when one’s sightlines are disturbed, the creature’s image recalls other ghosts, ghosts who still roil the land and its inheritors. The effect halts the viewer.

“And yet there is always something that places a human hold on the agnostic earth.” These words are written by Iduma, about Ractliffe’s photograph of a mass grave in Angola (Unmarked mass grave on the outskirts of Cuito Cuanavale, 2009). And yet these words meander across books to hold this untitled image from an unrecorded time and place too. If we let our eyes move across the page, we’ll see there is an outstretched arm, cropped but just visible along the bottom right edge of the frame. The hand holds up the bleached wood panel that frames the dead animal. This panel allows us to see the figure in starker relief, retrieved from its indifferent surroundings. Ractliffe cannot resurrect what is lost, but she can be its most steadfast witness.

This article original appeared in The PhotoBook Review, Issue 020, under the title “Clothing the Ghosts in Jo Ractliffe’s PhotoBooks.”