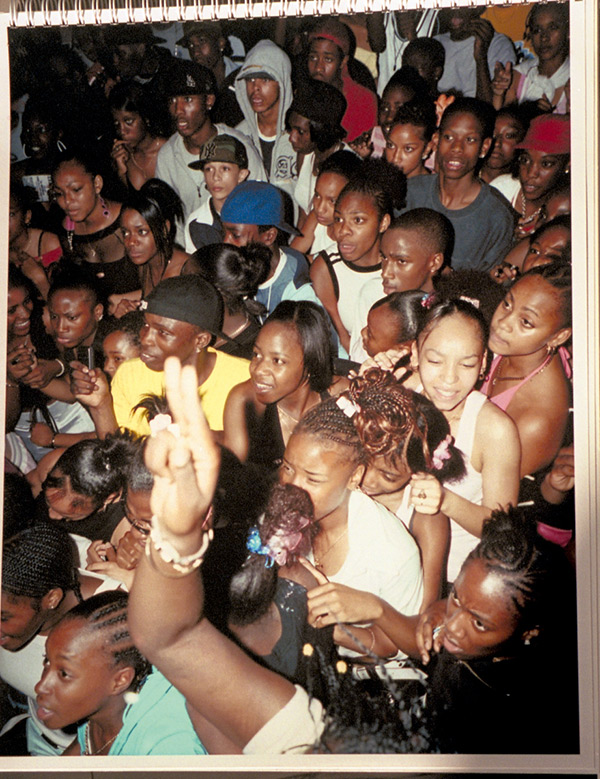

Liz Johnson Artur, Under 18th Rave, East London, 2004

Courtesy the artist

Shortly after midnight on June 14, 2017, a devastating fire tore through the Grenfell Tower public housing high-rise in West London. Seventy-two residents of the twenty-four-story building were killed in what was the most lethal blaze in postwar British history. Many Grenfell inhabitants were immigrants—first- and second-generation Africans and Arabs who had formed a disparate community in the building based on the common experience of departure from their homelands and arrival in Britain. They were the kind of people who had been vilified by tabloids and right-wing politicians over the past year of rancorous debate about Brexit. The kind of people, it was said, who were guilty of spreading crime, disease, and sharia law. As Katie Hopkins put it in a 2015 column for the Sun, “Some of our towns are festering sores, plagued by swarms of migrants. . . . Make no mistake, [they] are like cockroaches.”

Courtesy the artist

The Grenfell fire felt like a reckoning. Its ferocity had been exacerbated by the cheap and, as it turned out, highly flammable cladding materials used on the building’s exterior. In the wake of the blaze, with the tower looming over West London, blackened and sarcophagus-like, lurid talk of contagion and pestilence gave way to the reality of ordinary lives lost. The dead were not alien or other. They had been fragile and vulnerable and all too human. When the photographer Liz Johnson Artur first heard of the fire, her reaction was as personal as it was pained: “I thought, This could have been me.”

For many years, Johnson Artur lived in a public housing tower in Peckham, South London, built to the same careless standards as Grenfell. After the Grenfell fire, her building was condemned as unsafe, and the tenants evacuated. She now has an apartment, which also serves as her studio, in a sturdy brutalist-style tower built in the 1960s, located just south of the river Thames. From her thirteenth-floor balcony, you can see across the city to a thicket of new high-rise developments that crowd out the horizon, including the unlovely six-hundred-foot Vauxhall Tower, where apartments go for up to fifty-one million pounds. Johnson Artur is concerned with individuals and communities that live in the shadow of such buildings. “What I do is people,” she says of her work. “But it’s those people who are my neighbors. And it’s those people who I don’t see anywhere represented.”

Courtesy the artist

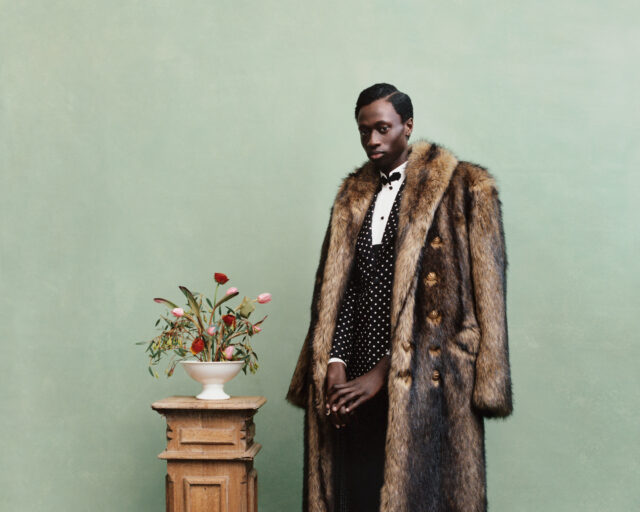

Johnson Artur’s people are, for the most part, of African descent. You might find them, long settled or recently arrived, in London, Kingston, Brooklyn, or any other place where diasporic scattering can land a person. They are ordinary black folk of ordinary income who are liable to be overlooked or stereotyped in the popular imagination because they don’t fit someone’s idea of what it is to be truly British or American or human.

For the past three decades, Johnson Artur has been capturing their presence in portraits of extraordinary nuance and empathy. She calls the body of work she’s accumulated across that time—an ongoing series begun in 1991—the Black Balloon Archive. (The name comes from a song by the soul singer Syl Johnson, which speaks of his delight at seeing a black balloon come into view against a snow-white sky.)

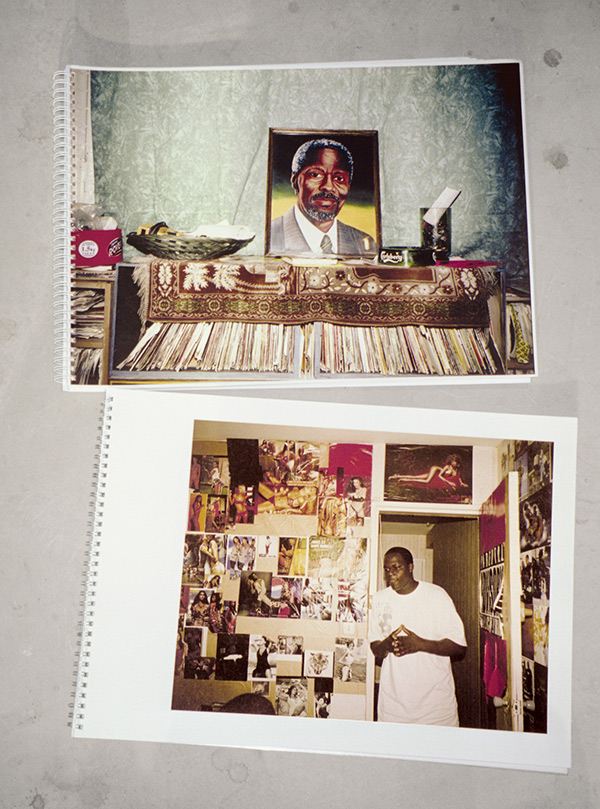

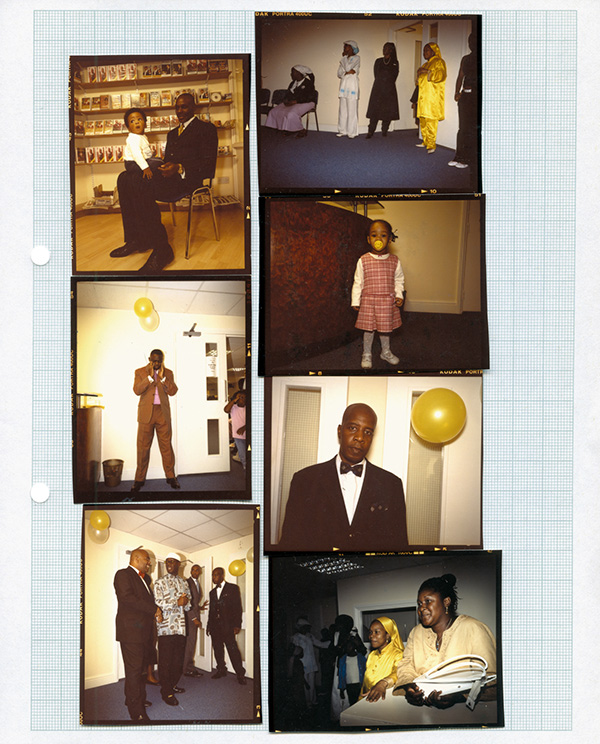

The shelves in Johnson Artur’s studio are laden with photography books and novels, vinyl records and magazines: Walker Evans, William Eggleston, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Richard Wright, Aimé Césaire, Milton Nascimento, vintage copies of National Geographic. The walls are decorated with photographs hand-printed by Johnson Artur—who shoots exclusively on film— on surfaces such as linen, tinted paper, and sheet music. The fullest manifestation of the Black Balloon Archiveis not on view, however. Stacked haphazardly among the shelves are volume after volume of notebooks filled with photographs and sketches; Johnson Artur has maintained them since she first started taking pictures. They function as a way to externalize her ideas, experiments, and moods, and together they best sum up how she approaches photography and what kinds of subjects and people she is drawn to in her work.

Courtesy the artist

Within their pages we can find African women in extravagant head wraps and sprucely dressed elderly West Indian gentlemen. Here is an all-male dance crew in Jamaica, its three members lined up in formation before the camera. And a group of young women glammed up, about to hit the club. One photograph shows a young man flashily accessorized in gold chain, spangly watch, Nike headband, and blue baseball cap. He eyes the camera with adolescent self-regard. The image has been printed on what looks like powder-blue leather and stapled into a notebook. Over it, stamped in red ink, are the words, “One day someone is going to beat him.” The message is as elusive as it is disturbing. Is it a warning? A rebuke? A quote? Or simply an acknowledgment of the brevity of youthful insouciance?

Elsewhere. Another photograph. We are at a club or a gig before a crowd of kids. They are all facing forward, perhaps in the direction of a performer or a DJ onstage. The young women have hair that’s straightened or braided or, in one case, woven through with copper-colored extensions. The boys mostly wear hoodies and baseball caps. They all look eager and excited to be there. Gazing at them, we see the variety of their skin tones—honey, chestnut, umber, rust red. And we notice how, in that moment, caught in elation, each of them is so very beautiful.

Courtesy the artist

Exactly how Johnson Artur establishes the trust and connection necessary to conjure moments of such intimacy is a mystery, especially given that she often shoots in hectic conditions, among crowds or out in the street. There’s also a larger question raised by her work. Gazing from face to face in her photographs, we might. ask of her subjects, Where are you from? It’s a query that bedevils all diasporic peoples, casting doubt as it does on the legitimacy of the immigrant’s place among the indigenous. But the same question can be phrased more benignly when it is asked between immigrants. All of us whose origins lie abroad can share an awareness of the battle for belonging that we, our parents, or our forebears fought in order to call the country we live in home. There’s pain in that thought. We might picture ancestors shipped across the ocean as human cargo, for instance. But we can also feel pride at how our persistence, our collective strength, has brought us to this present moment. So, rightly, we can wonder what historical forces have shaped Johnson Artur’s subjects. And we might even ask the same question of the photographer herself.

Courtesy the artist

Johnson Artur was born in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1964. It was there that her Russian mother, Nina, met her Ghanaian father, Thomas. She, in the city to study radiology. He, one of a small group of around twenty African students benefiting from a cultural relations program between Eastern Bloc nations and the developing world. They had only known each other a few short months when Thomas and his fellow students were expelled after a fight between an African student and a Bulgarian soldier. Nina and Thomas remained in contact, but with her unwilling to follow him to Ghana, their relationship dwindled. By then she was pregnant with their daughter. When the baby was born, the girl’s surname fell victim to bureaucratic mangling, becoming a bowdlerized version of her father’s name, Johnston Arthur. At that time in Bulgaria, single mothers risked having their children put into foster care. All the more so if the child was of mixed heritage, and if the mother belonged to the loathed Russian occupying power. They endured in Sofia until, when Johnson Artur was five, her mother inveigled passage to Duisburg, West Germany. They arrived without money or a place to stay and ended up in a former air-raid shelter turned homeless hostel. It was cold and damp, and Johnson Artur caught pneumonia. A doctor treating her took sympathy on them and gave her mother a job. They were able to move into a room in an accommodation block for nurses. Determined to save money for their own house, mother and daughter continued to live this way, in a succession of dorm rooms, until Johnson Artur was in her teens.

Courtesy the artist

Aged nineteen, Johnson Artur left Cold War Europe for the first time, to visit New York. The trip was a defining experience. It was 1986. The streets pulsed with the sounds and styles of hip-hop: Eric B. & Rakim, Biz Markie, Run-D.M.C., gold chains, Adidas Superstars, leather tracksuits, Boogie Down Productions. The spectacle was intoxicating. But Johnson Artur could only look on from a distance. Her mother had arranged for her to stay with a Russian family she knew. Although the family lived in a black neighborhood of Brooklyn, they maintained a fierce separateness from the community around them, and they encouraged their visitor to do the same.

On one occasion, they took her to a restaurant in the Russian enclave of Brighton Beach. Onstage, as entertainment, four black women dressed in Ukrainian outfits sang Russian folk songs, inviting patrons to laugh at the apparent absurdity of black people versed in the culture of Eastern Europe. For Johnson Artur, the Ghanaian Russian born in Bulgaria, the episode was disturbing. “I didn’t know how to feel about these women. I didn’t know how to feel about sitting at this table. I felt Russian, but at the same time I felt that I was at the wrong spot. It freaked me out.” Until that moment, she’d thought of herself essentially as an émigré Russian, like her mother. In Bulgaria and Germany, her Ghanaian heritage had felt like a distant detail. “I grew up with my relatives telling me, ‘Yes, you’re black, but you’re not that black,’” she reflects. “I didn’t explore blackness because I didn’t see it as relevant.”

Courtesy the artist

In New York, she felt a powerful affinity for a people and culture she barely knew. “It was the first time where I thought, I have to somehow find out where I belong.” With a camera she’d hardly used until then, Johnson Artur began to explore the city, hoping in the process to discover a version of herself that accommodated race as well as nationality. “I think from then, from that trip, that’s where I started taking photographs.” She returned to Germany and studied photography with the aim of getting back to New York as soon as possible. But she still had a Soviet passport, and travel was difficult. Instead, she ended up in London, where she studied for an MA at the Royal College of Art. By the mid-1990s, Johnson Artur was taking pictures for style magazines such as i-D, The Face, and Arena. She traveled frequently on their behalf, to the United States, the Caribbean, and Africa. On each trip, she took time to slip away and wander local neighborhoods, camera in hand. “I was hungry for experience. I was hungry to meet people,” she says. And she discovered that, irrespective of location, she was able to establish the same easy rapport with those she encountered. “If you walk around and you are all by yourself, it seems very scary. But I find it easy to approach people, and there’s an empathy that follows. It’s a give-and-take. I take all these pictures because people let me.”

Courtesy the artist

The same desire for connection continues to drive her today. At the 10th Berlin Biennale, in 2018, where her work was featured, Johnson Artur presented images from the Black Balloon Archive, alongside a new video titled Real…Times (2018) that interweaves scenes of black life, some of which Johnson Artur chanced upon in the street. Like the footage of the middle-aged man being handcuffed and hauled into a police van, maintaining innocence of whatever he’d been accused of, while friends and passersby looked on in consternation. Or the West Indian men and women gathered in a public square in South London to both celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the Windrush generation—the Caribbean settlers whose arrival in the U.K. marked the start of postwar mass migration—and protest how the government’s self-described “hostile environment” policy for immigrants now threatens to withdraw the status of British subject from those same settlers.

In the video, and throughout Johnson Artur’s archive, we glimpse a myriad of sentiments: joy, pride, defiance, loss, and a desire, above all, to be fully visible, to be seen and heard on one’s own terms. The faces before us in those photographs are strangers. But in the immediacy of each image, they seem familiar, as though we’ve known them all our lives. Maybe this is what kinship is like? Identity built on a shared past. On moments of hope and pain that stretch back further than we can remember. Back into history. Back beyond those ocean crossings. And perhaps then the Black Balloon Archive might be a meeting point for those pasts made present. A family album for the diaspora.

Read more from Aperture, issue 233, “Family,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.