Malala Andrialavidrazana Redraws the Map

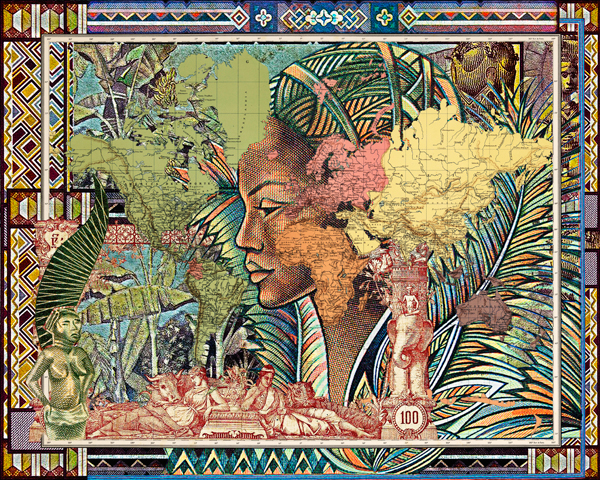

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Figures 1889, Planisferio, 2015

© and courtesy the artist; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

For the past fifteen years, the photographer Malala Andrialavidrazana has traveled to nations along the Indian Ocean, and across Asia and Latin America, to capture the cultural mutations of contemporary societies that are evolving between tradition and galloping globalization. With patience, she observes cities, their inhabitants, their ways of life, and the interiors behind the scenes, in order to overturn clichés. Her images consistently draw the contours of a plural singularity through recurrent motifs, while revealing the proximities as contradictions. In her series such as d’Outre-Monde (2003), Tanindrazana / The Ancestors’ Land (2005), and ECHOES (from Indian Ocean) (2011–13), this is manifest through seriality of documentary-based photography. Figures (2015–ongoing), her most recent body of work, unveils a different phraseology: each photomontage in the series is composited from signs and symbols of the past—precolonial maps, bank notes, album covers, and stamps—which offer multiple readings to see the world new and again.

Born in 1971 in Madagascar, where she lived before settling in Paris at the age of twelve, Andrialavidrazana fuels her practice by moving from one country and one culture to another, taking a look with respect and sensitivity to capture, in the words of fellow Madagascan artist Joël Andrianomearisoa, “the slightest shivers of life without either geography or bias.” Andrialavidrazana’s education in architecture also informs her photographic practice. By looking at the world through three-dimensional sight, Andrialavidrazana uses her images to create new forms of circulation. At a moment when the Great Powers of the Western world are facing a rise in populism and its bedfellow, essentialism, the impetus to go beyond fear and stereotype could not be timelier. Here, Andrialavidrazana speaks about how she builds images, and her relationship to architecture, travel, and geography.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Tanindrazana / The Ancestors’ Land, 2005

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Sonia Recasens: Madagascar plays a very important role in your work. There appears to be a continual back-and-forth between the intimate and the universal, the local and the global, the private and the public. These comings and goings reflect your own movements between Paris, where you live, and Madagascar, your ancestral homeland.

Malala Andrialavidrazana: I’m proud of my Malagasy roots because of the elegant way people in Madagascar consider women in social and family life, and because of the multiple connections to various cultural areas. My Malagasy roots are part of my way of thinking, so that’s why there is this back-and-forth. This is one part of me and the other is very Parisian. Nobody is perfect [laughs]. I use this dual cultural background to move from one point of view to another when I really need to think about how to tell stories about the Others.

Missla Libsekal: You came to photography by way of architecture. Could you tell us about that journey?

Andrialavidrazana: While studying at École d’Architecture de Paris-Conflans in the early 1990s, there was an optional training program in photography and video. I didn’t want to just build things; I also wanted to write and tell stories. During my childhood, I had my own camera that I used when we travelled with my dad. He was a very serious teacher; when we received the photographic prints, he always commented on the meanings within pictures. Learning to see was almost on the same level as learning to speak, to read, and to tell stories.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, ECHOES (from Indian Ocean), 2011–13

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Libsekal: When did photography replace sketching for you?

Andrialavidrazana: When I took a round-the-world trip in 2003, I thought it would be more convenient to travel with a camera than ten sketchbooks. I still take pictures in the same way as if I was drawing, to focus on details. And I can also remember telling myself in the late 1990s that I didn’t want to spend my whole life drawing lines on a computer!

Recasens: Your photographic practice feeds on architecture but also anthropology, history, and geography.

Andrialavidrazana: Architecture is generally understood as the construction of new ideas, hopefully for a better world. I felt strongly that it was possible to be an architect and construct with lighter materials—images and words.

Recasens: To construct images, but also to deconstruct the exotic clichés about the Other and the “elsewhere”?

Andrialavidrazana: Exoticism is related to the contrast between the Western and Southern world—developing countries that have less possibility to talk about themselves. So, of course, when I see it as a system of power, exoticism generally refers to the condition of master and servant. But as a kid, before moving to France, Europe used to be an exotic thing for me. It’s always a question about the point of view, which depends on where, and whom, you are talking to.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, ECHOES (from Indian Ocean), 2011–13

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Libsekal: The poet Langston Hughes called his autobiography I Wonder as I Wander. Likewise, movement has been present since the start of your career, as you produced series shot in India, Madagascar, and other locations. Can you speak about this duality of curiosity and movement as much of your image-making has happened while traveling?

Andrialavidrazana: I don’t really wander by accident … I wander where I can find attractions [laughs]. Traveling is the key to meet the Others and to better understand specificities, differences, and eventually to find commonalities between the Others and myself. In French we say, On n’apprend jamais autant qu’à travers nos propres expériences (The things that you really know are the things that you’ve learned from your own experiences).

Libsekal: But, travel photography can inadvertently encourage exoticism of the Other.

Andrialavidrazana: One of my first rules is to meet the locals. I always research in advance, planning logistics and contingencies, and I also get local contacts in order to go beyond a touristic, superficial view. I prefer to have different perspectives, to get out of my comfort zone and preconceived ways of looking at cultures or people.

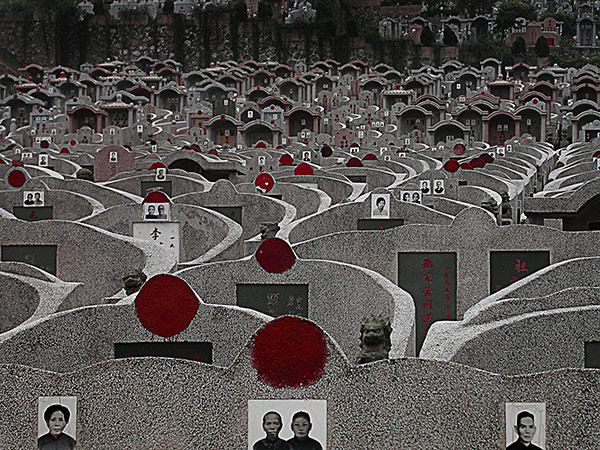

Malala Andrialavidrazana, d’Outre-Monde, 2003

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Recasens: Your series on funerary burials and traditions, Tanindrazana / The Ancestors’ Land and d’Outre Monde, reveals a sensitive relationship to loss, absence, and disappearance. Where does your sensitivity come from?

Andrialavidrazana: It relates to living people. As an architect, I considered all the buildings and monuments that living people build for the dead. In French it’s said, La mort, dévoreuse d’espace (Death sucks a lot of space, and costs a lot of money). There are people who don’t even have housing! It’s not normal that many families live in tiny spaces, and that balanced solutions don’t exist. It was about getting into these questions.

Libsekal: By using spatial configurations as a photographic paradigm?

Andrialavidrazana: Rituals change depending on geography and influences. I chose cosmopolitan or multi-religious places to see how people living in the same space would get together when they die, to understand how human beings deal with heritage, globalization, and fashion. Even in funerals there are fashionable things. This is a way to embrace the complexity of the contemporary world.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, ECHOES (from Indian Ocean), 2011–13

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Recasens: This sensitivity to worship and to the spiritual appears in d’Outre-Monde and Tanindrazana, but also in ECHOES (from Indian Ocean), with references to ritual objects and effigies. Is this your way of making a community’s portrait?

Andrialavidrazana: I observe traditions because once you go out of the big cities, that’s how people live! The smaller villages and cities are where traditions are more often upheld. This is apparent in major rites of passage including birth, weddings, and death, when ceremonies are influenced by familial heritage and local infrastructure. You cannot erase traditions from the way that you describe a country. So, talking about trendy things and new ways of living is one thing, but we also have to look at the way traditions mix with outside influences.

Recasens: In multiple series, the recurrence of familial objects—textiles, sheets, curtains, blankets, shoes, music, and religious effigies—offers a plural singularity, yet also hints to some contradictions.

Andrialavidrazana: There are some contradictions as these traditions change with globalization. In the last ten years, the ability to access news, international movies, and music from abroad has increased. Markets are more globalized. Ideas and objects move quicker than people.

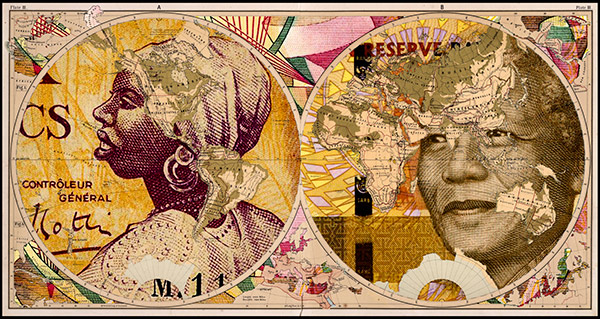

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Figures 1861, Natural History of Mankind, 2015

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Libsekal: Representational photography, particularly portraiture in Africa and about Africans, is indeed ubiquitous. On the other hand, you and peers, such as Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, are presenting alternate subjectivities.

Andrialavidrazana: Despite the fact that I want to go beyond clichés, my projects often come from specific geographies. Instead of focusing on individuals, I try to find the commonalities—details, things, attitudes—that would speak to more people because I try to tell stories about people who are not very visible.

Libsekal: Figures, your new and ongoing series, is photographic, but it could also be considered a form of printmaking, of digital collage, and of historical recovery. You presented Figures at the 10th Bamako Biennale in 2015. What was the significance for you of showing this work in Mali?

Andrialavidrazana: “Telling Time” was the theme of the 2015 Bamako Biennale. As curator Bisi Silva noted, the exhibition was an opportunity to look back in order to move forward. Previous editions of the biennale have always paid attention both to archives and alternative identity or geographical representations. In fact, Figures combines these various fields by using materials such as precolonial maps and currency notes. We should always remember that cartography was among the most powerful political and ideological tools during the nineteenth century. In the same way, banknotes often conveyed stereotypes promoted by consecutive regimes and leaders. The roles of these printed documents are not so far from those of photography.

After completing ECHOES, I felt that something was missing in my practice. I did not want to start a new project using a camera exclusively, nor in a standard mode. I was willing to draw again, to tell stories in a different way. That is how I began exploring archives. Figures is still a camera-based project, but it’s not written in the same way.

Recasens: Yes, it has a more plastic dimension, close to drawing or collage.

Andrialavidrazana: It’s more related to drawing, and also close to writing for me. When I mix all the figures and details together, it is like writing—creating different phrases within a picture frame. I think my practice is a mix of wondering and writing, rather than just taking pictures.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Figures 1867, Principal Countries of the World, 2015

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Libsekal: Figures reads like an exhumation of pictorial legacies, iconography embedded in the tools of modernity that historically facilitated the movement of goods and people. Given the contemporary transition to digital technologies and cashless societies, what made the past and archives so interesting?

Andrialavidrazana: The materiality of archives is really changing as many documents are now virtual, and data transmissions occur through websites more than by hand. When I decided to go back to those materials, at first I was attracted by their beauty. What is important in these documents are the messages the Great Powers used to symbolize their poetic and social values that entered into the social imaginary, to become a part of what you think the world looks like.

Recasens: How would you explain the series’ wide media coverage and critical success? Does the series reflect societal concerns and our relation to history and archives?

Andrialavidrazana: When people look at the compositions from the series, they can realize that for most of those stories written into these archives, there are multiple interpretations. The fact that Figures has become successful certainly speaks to the power of these archives.

Recasens: Coming back to your creative process, the neat framing, the usage of shadows and light or the highlighting of textures of walls, textiles, and skin is very powerful. It’s photographic, but also pictorial.

Andrialavidrazana: Critics have often said that I work like an anthropologist in the way that I capture details. When I meet a subject, I don’t remain in the same position. I really need time to take a picture, to turn around in order to go beyond appearances. I can’t be satisfied by a unique angle. I am used to thinking in a three-dimensional way; that’s why shadows, textures and light become important!

Recasens: Lastly, do you imagine “writing” in other mediums?

Andrialavidrazana: I can’t tell the future, but, that said, photography is my singular tool to write what I would like to say.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives. Limited edition prints by Malala Andrialavidrazana are available from Aperture Foundation.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.