The Renegade Video Artist

Mary Lucier, Equinox, 1979

Courtesy the artist

When video emerged as an artistic medium in the mid-1960s it was, as Mary Lucier puts it, a “renegade” form: low-resolution, ephemeral, woefully connected to the debased cultural products of television, and, for some, hopelessly “narcissistic” in form and content. It was a medium that had no past and seemed to have no rules, except one: never point the camera at the sun. Doing so would permanently burn and scar the vidicon tube inside. Lucier, who has worked across media including film, photography, performance, and choreography in her nearly fifty-year career, made her mark by breaking this rule. Her early video installations, such as Fire Writing (1975), Dawn Burn (1975), and Equinox (1979), which was just recently restored and exhibited at the Columbus Museum of Art, used the medium against itself, overwriting real-time images with indelible accretions of the past.

Kris Paulsen: I want to focus our conversation on Equinox (1979), a seven-channel video installation that was recently restored for the Columbus Museum of Art (CMA) exhibition, The Sun Placed in the Abyss. Before we get there, I want to ask how you got into video in the late 1960s, when it was still a very new medium?

Mary Lucier: I got into video primarily because I was doing performances at the time, in the mid-’60s into the ’70s. I was working with my first husband, the composer Alvin Lucier, and I was involved with the time-based work that was happening at that time in dance and in music, and I thought it was really the most advanced art of its time. I got involved in performance art and I was very close to Shigeko Kubota and Nam June Paik. At some point through their influence, I decided I wanted to use video, so I borrowed a camera and started shooting video and that became a whole thing in itself—not just a part of the performance. So eventually that moved into installation. I had studied sculpture as a college student, and video installation struck me as a form of sculpture. I thought, this is three-dimensional, this is how I want to work.

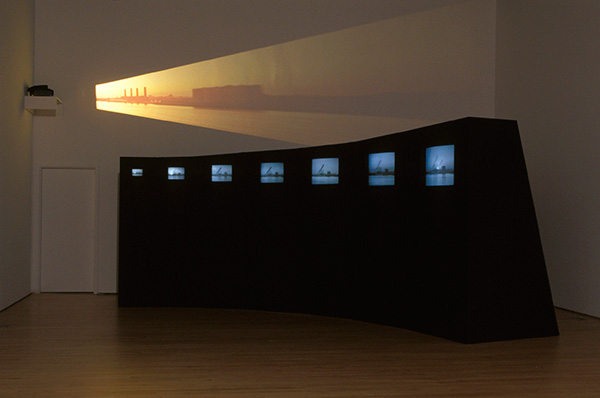

Mary Lucier, Dawn Burn, 1975. Installation view at the Columbus Museum of Art, 2016

Courtesy the artist, the Columbus Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Paulsen: Equinox is on display for the first time since it was commissioned in 1979 for the CUNY Graduate Center. I want to ask about the impulse behind this work and others you made in the 1970s, particularly Dawn Burn. In these works, you break the number one rule of analog video making: you point the camera directly at the sun. Doing so burns a permanent black spot into the vidicon tube. Everything you record from there on out is marked in that same way. In Equinox, you point the same camera at the sunrise for seven days straight. Each day is on a different monitor and shows the day-by-day accretion of tube burns in a series of arc across the frame. What inspired you to break that rule?

Lucier: Well, I have to say the first impulse was probably just to break that rule. In the early 1970s, video itself was still a new medium, and a medium that in many ways was breaking rules with conventional film and other kinds of visual art making. It was not universally liked as a medium. It was renegade and its quality did not match film, even 8mm, of the time. And yet it was very expensive. It had this roguish quality, as if we were doing something that was a little bit elicit. So, since I was already breaking the rules by using video, I then decided I wanted to break its very first rule and see what would happen.

Paulsen: Was the result what you expected?

Lucier: I did tests before I actually made a complete work. So, I did know what was going to happen, more or less, and how the sun was going to scar the internal tube of the camera. That’s the other thing I was certainly interested in—the scarring process and how, if the camera is the substitute for the eye, you’re actually, in a sense, scarring the retina of the camera.

Mary Lucier, Dawn Burn, 1975

Courtesy the artist, the Columbus Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Paulsen: That’s one of the things that I think is so visually, metaphorically, and poetically powerful about Equinox and Dawn Burn. It makes the video image material, and makes the camera into an individual, particular thing. It’s not a disembodied eye but an embodied, unique individual machine, and that camera tube is marked physically by that vision. There’s an incredible double-sidedness or reciprocity in the image: You see the eye that is seeing at the same time as you see the image itself.

Lucier: And obviously the tube retains what I call “the memory of that moment,” and anything else that you look at through that camera with that tube is going to have the markings of that memory, of that moment.

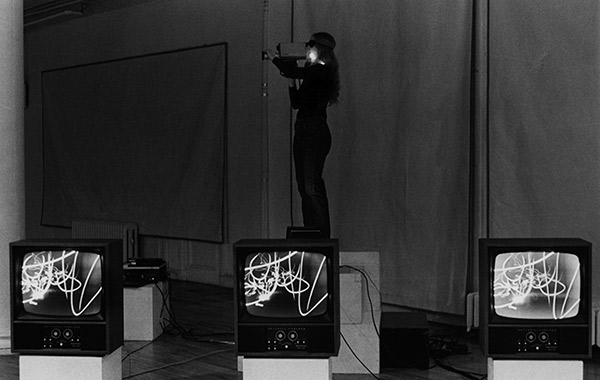

Later, I reused some of the damaged tubes that I burned with lasers in a series of pieces called Fire Writing, where I wrote in the air, so to speak, with laser beams aimed at the camera. I tried to replicate text that was being spoken in the room. The burn marks of the lasers are much more intense—they’re very white. So you have this build up of white calligraphy on the tube that becomes quite extraordinary after a while. I later exhibited them as drawings.

Paulsen: And after a while of recording the light writing with the laser in the room, does the image of the room become completely obscured by the remnants of the laser burn on the tube?

Lucier: It can and the longer it goes on, the more the tube is obscured. But one of the things I did like about it is that even near the very end of that “performance” you can still see faces; you see them through the veil of this calligraphy. I have always liked that.

Mary Lucier, Fire Writing, 1978. Performance at The Kitchen, New York

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: That’s fascinating, since video’s essential properties, at least as they were being discussed around that time in the 1970s, were connected to the idea of an unrelenting present. But you have this way of retaining a kind of past in live image, whether it’s of this physical, embodied memory or these more literal inscriptions within the image. The image becomes thick with time rather than just delivering the real-time image of the present.

Lucier: That’s absolutely true. It actually imprints the moment. It also compresses whatever is happening. Particularly, in the writing pieces, it compresses the entire text. By the time the piece is finished, all the text theoretically is there on the screen even though you can’t read it but theoretically, you could unravel it and read it somehow. That was one of my ideas about it. When I displayed them as other installations, I also left the cap off the camera so that you can see—

Paulsen: Yourself?

Lucier: Your own face through the burn markings.

Paulsen: The present in the background is being renewed but the past is always in the foreground clouding that vision.

Lucier: You’re right: the markings are always in the foreground and then the real-time image becomes kind of background.

Paulsen: In that way, it erases that idea of transparency or immateriality that video images seem to have. We assume that they give us a direct view of the world unfolding in front of the lens. But this camera’s previous life is always going to be present and affect it, rather than the image being constantly renewed again or refreshed.

Lucier: Exactly.

Mary Lucier, Fire Writing, 1978

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: When I was watching you install Equinox at the CMA, you were “tuning” the colors across the seven monitors. It made me wonder about your use of color in Equinox. A sunrise is, of course, a colorful thing, but color seems to be a definite choice, especially since Dawn Burn and Paris Dawn Burn were black and white.

Lucier: Well, everything was moving toward color when I started making video in the very early ’70s. Somebody, maybe Nam June Paik, brought back the first color camera from Japan and everybody kind of flipped and started experimenting with color. The thing about black and white when I made Dawn Burn was that the black markings were so heavy.

Paulsen: Yeah, they are almost sooty.

Lucier: You could look at it as though it was charcoal drawing, let’s say, and when you look at the whole image of the river and the boats and the sun marks on the tube, they’re like black-and-white drawings to me. The marking was very important to me in black and white and how the markings revealed this shape of the earth moving around the sun. It has a very specific shape. It starts as a smallish thing and seems to get larger as it rises in the sky.

Color became the central thing about Equinox. I realized that this summer when I was transferring it from analog to digital and just staring at these images on the screen and thinking, my god—it’s all about color!

Mary Lucier, Equinox, 1979

Courtesy the artist

Paulsen: You bring up transferring and restoring the work this summer. What was the experience of seeing this work again after almost forty years?

Lucier: It was kind of thrilling. I got very wrapped up in making the transition into digital. I had never thought the color aspect of it as being as critical as it is. When you’re transferring from analog to digital qualities change, and I certainly think this was one of the qualities. The color really popped up in the transition and I was just blown away by how much I enjoyed it.

Paulsen: I wonder if that pleasure was a product of digital transfer or the distance that you’ve had from it. Maybe you were also surprised by the particular look of analog color after it’s been gone from our daily lives for so long? We don’t see those kinds of colors anymore. It moves across the screen in such a fluid way. For Equinox, this was the critical moment for transferring a nearly forty-year-old videotape, which is nearing the end of its lifespan. This is the case for all early video works. I wonder what you are doing to preserve your work?

Lucier: Preservation of video is a major issue now. Even if you successfully transfer something to a digital format and you have it as a digital file, there’s no guarantee you’ll be able to play that forever, either. It’s essential to get it all down on digital in some format that I can live with, and then that’ll be its copying format for the future, not the original tape.

And that’s scary because what’s to guarantee that this file will play in even ten years? What’s to guarantee that there’ll be a device that will play it, that you’ll be able to insert it into a computer that accepts that format? Will you always be able to do that?

Mary Lucier, Paris Dawn Burn, 1977

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: Do you ever think about a kind of “living will” for your works, indicating what you would want or intend for them especially once collected? Would you be willing, for example, to allow them to be shown on flat monitors? Have you thought about contingency plans if these old style analog monitors are no longer in production?

Lucier: Yes, I think there is an advantage of there being a living artist attached to these works as museums collect them. SFMOMA did a huge interview with me, asking how I saw the future of this work, what I wanted Dawn Burn to be. I think that’s very important. If you can catch the artist while they’re still alive and get their take on what they want for the future and what they would allow. You’ve got to be able to think about ways that you can transform the work as the technology transforms. So, I am indeed thinking about that.

Paulsen: This is a particularly important question for works like Equinox and Dawn Burn, which are on analog technology but are also about analog technology.

Lucier: Right, and I really wanted this piece to be in its more or less original context. This was something I talked about with Greg Jones from the CMA: what is the best compromise we can strike between the way it looked originally and the way it could look now and still be authentic? I could never do anything to change Dawn Burn. It exists as is. It is a programed piece. It is fixed. It’s a conceptual piece that cannot change whereas I don’t feel that way about Equinox. I feel that as long as I keep it essentially the same, I could change many interior things. I feel I have the liberty to change them in certain ways if I wished.

Paulsen: So, do you?

Lucier: Embellishments—not to the change the essential concept of it, and maybe not to change the original materials, but to change certain aspects of presentation.

Mary Lucier, Paris Dawn Burn, 1977

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: Do you think that the work that you’ve had to do around preservation has prompted some of these re-imaginings?

Lucier: It does make you look back at things, and it does open you to the question. I keep thinking of Bruce Nauman, because his pieces keep being redone, and he made a comment about a recent piece he did—a new piece—he hadn’t made a new piece in two years. It’s a version of his contrapposto walk. He said there were things he felt he needed to redo and I applaud that because if there’s anybody who you would think wouldn’t change a thing, it’s Bruce Nauman. It was process art. So I love the idea that he would take the liberty to go back to an older idea and rework it in some way, and I think that’s a great liberty now for many of us because we’ve had some great ideas in the past and they haven’t been used up.

Paulsen: Hearing you talk about Equinox just a little while ago was really wonderful. I loved your surprise realization that the color was different than you had remembered and that it was more important. Its effect on you was different. Encountering a work from the past can give it a new narrative, even to you.

Lucier: Absolutely. That’s a great way to put it.

Paulsen: It’s like a long feedback loop.

Lucier: It’s a loop and you’re allowed to make changes in that loop as it comes around again. There are certain scores written on paper that would do the same thing. Lamont Young, Yoko Ono, John Cage, Robert Ashley, all the composers I knew, wrote scores that weren’t music notes on a staff but were conceptual ideas. I think some of the best scores were like that and I still very much admire that way of working and see the permissiveness to go back into it and to make some changes.

Paulsen: Right, scores are meant to be interpreted—

Lucier: Interpreted!

Paulsen: And played again.

Lucier: Exactly. Who knows, I might change my mind someday. I could imagine completely redoing Dawn Burn. Let’s say, reshooting it from beginning to end. That would be permissible, because in a sense, it’s a score, too.

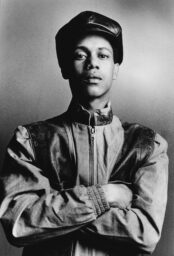

Mary Lucier, filming site of Paris Dawn Burn, 1977

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: And it seems like that score gave birth to Paris Dawn Burn and to Equinox, so it is already in a series of interpretations and reopenings.

Lucier: You’re right—you’re absolutely right about that. Probably if I had more opportunities, I could continue doing various iterations of that overall idea. Already Paris Dawn Burn is different from Dawn Burn. Dawn Burn has no sound. Paris Dawn Burn has a wonderful soundtrack with the morning bells of Paris.

Paulsen: That’s the thing about sunrise: a trip around the sun or a rotation around our axis, it’s iterative everyday. It happens again each day but each day it’s different.

Lucier: Each day is different—exactly.

The Sun Place in the Abyss was on view at the Columbus Museum of Art from October 7, 2016 to January 8, 2017.