Massao Mascaro, Sub Sole, 2017–21

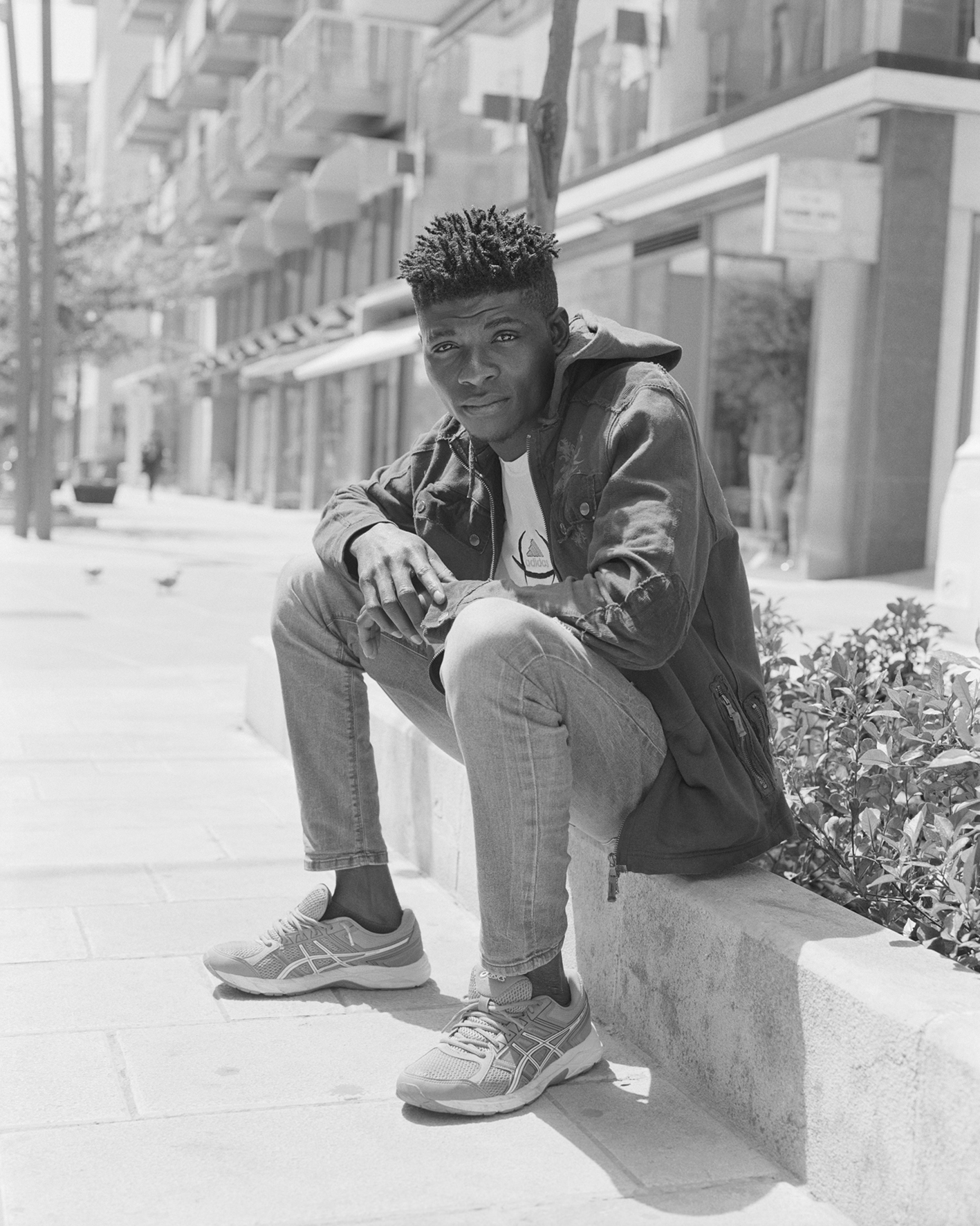

Massao Mascaro’s new series and photobook Sub Sole (2021) takes place around the Mediterranean Sea, the crucible of many journeys—some recent, real, raw, and grievous; others ancient and mythological. The interplay between past and present defines the quiet majesty of Mascaro’s observant eye, as he gazes across architecture, hair, skin, ruins, trees, streets, and the tentative gestures of friendship and connection.

Mascaro was born in Lille, France, in 1990 and studied photography in Belgium. After two published works, Ramo (2015) and Jardin (2019), in which he developed a distinctly poetic, slightly bleached-out black-and-white style, he was granted a fellowship by the Fondation A Stichting in Brussels—where the series Sub Sole is on view through December 2021, after a presentation at Les Rencontres d’Arles in France. The Fondation A Stichting grant gave Mascaro a certain liberty to imagine a new project, one that would lead him, like Odysseus, to the Mediterranean Sea. By the end of his three-year itinerary, Mascaro had visited Ceuta, Naples, Athens, Palermo, Istanbul, Tunis, and Lampedusa. “I resorted to literature and poetry and started collecting sentences,” Mascaro told me recently. “Then, I started to build photographic sequences using ideas borrowed from literature,” specifically Eugenio Montale and Jorge Luis Borges.

The evidence of this crosspollination is marked in the titles of Sub Sole’s chapters, which also help intertwine Mascaro’s metaphorical work into one solid piece, starting with “Aujourd’hui” (today) and a vision of our time’s sea, partially blocked by an iron column that separates the landscape. The sea, Mascaro says, “is always a metaphor in the book.”

In the second chapter, “Porti e porte,” Mascaro questions the sea’s capacity of being both a door and a gate. “If you choose to cross the Mediterranean, legally or illegally, it is because you think there must be a door; at the same time, the door can be open or can be closed, and you never know that before standing in front of it,” Mascaro says. He returns to this duality in chapter five, “Hôte, hôte.” Mascaro explains that, in French, the word translates as both the one who welcomes and the one who is welcomed. “One should probably add that, in Greek, the word xenos, which means hôte in these two senses, also means stranger, the one who must above all be given hospitality.”

But who is given hospitality in the worst contemporary migration crisis? Mascaro’s pictures, working with the idea of absence and presence, hint at this question; a braid is completed at the beginning of the chapter and undone by its end. Mascaro captures the Mediterranean story through the people and objects in front of him and beneath the sun, hence “sub sole.” But the context in which Mascaro pursues his noble perspective of capturing all things on equal ground is fraught: the death toll of migrants seeking refuge in Europe may be lower than in the mid-2010s, but lives and boats lost to the sea are a tragically regular occurrence.

Mascaro’s choice not to include captions for the images in Sub Sole places him first as a confidant. “I always ask people to photograph them and, on all occasions, the process starts with me simply speaking to them,” he says. The register of that encounter is shared with us through images, but the verbal exchange is kept between photographer and subject. Mascaro speaks Italian and Spanish, “so it was easy to talk to people in most countries I visited for Sub Sole. But, because I was genuinely interested in their stories, sometimes I didn’t feel I had to take their picture; I just had a conversation and said goodbye.” For years, he adds, everyone saw the same tragic story on TV. “I wanted to know all their stories.”

In Mascaro’s work, can the political and poetic merge? Looking at the images in Sub Sole, I thought of James Baldwin’s words in Giovanni’s Room (1956): “Somewhere beneath this tense fragility was a strength as various as it was unyielding.” A portrait that exists alongside or within the tragedy of migration does not preclude or erase it. For the people Mascaro encountered, there is life ahead, and further unknowable journeys. Still, the photographer doesn’t deny pain, although he may deny the easy refuge in shock.

Sub Sole exists in a state of suspension: while there is warmth coming from the young people of various races and identities that form Mascaro’s “agora” (the ancient Greek gathering place), there is also a note of hopelessness hanging in the air. “Porti e porte”—a door can be a gate. The ruins featured in this mythological location reinforce this feeling. A one-time sovereignty now rests shattered in pieces. Who was welcomed and who was denied? “I have been Homer; soon, like Ulysses, I shall be Nobody; soon, I shall be all men—I shall be dead,” Mascaro quotes from Borges’s short story “The Immortal” (1947).

For the closure of Mascaro’s wanderings, with images of lettering strewn on the ground, a throng of swimmers in the water, and three disconnected handsets dangling ominously from a phone booth, Mascaro looks back at the beginning: the alphabet. “In my readings about the Mediterranean, I discovered that, in fact, the alphabet came from their civilization.” One of the most ancient steles with Phoenician inscriptions dates from circa 850–740 BCE, and was discovered on the island of Sardinia. “The letter A, for example, comes from the pictorial representation of the head of an ox,” Mascaro says. “I enjoyed the idea of the last chapter being composed of pictures that go back to letters and alphabets.”

Courtesy the artist

Massao Mascaro’s Sub Sole was published by Chose Commune in 2021; his exhibition of the series is on view at Fondation A Stitching, Brussels, through December 19, 2021.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.